One of “the most beloved gospel songs of all time” achieved that status by offering Americans hope during some of the darkest moments of the 19th and 20th centuries, according to Robert Marovich, founder and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Gospel Music.

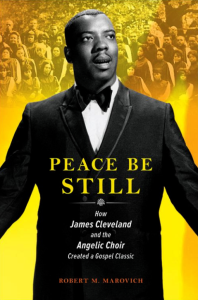

“Peace Be Still” was written by white Protestants in 1874 to teach Sunday school children about Jesus calming the storm in Mark 4. After a rise in widespread popularity, it eventually fell into obscurity before being revived with great acclaim by Black Baptist singer/composer James Cleveland and the Angelic Choir in 1963, said Marovich, author of Peace Be Still: How James Cleveland and the Angelic Choir Created a Gospel Classic.

He spoke during a recent webinar presented by the Baptist History and Heritage Society.

Robert Marovich

The song, Marovich said, reached both white and Black Christians with “this sense of overcoming, resisting and emerging victorious through Christ.”

“We know that the song … was somewhat popular when it first came out. It was sung at funerals in addition to Sunday schools. For example, when President Chester Garfield was assassinated (in 1881), ‘Peace Be Still’ was sung at his funeral service.”

The hymn was written by Horatio Palmer, choir director at Second Baptist Church in Chicago, and Baptist temperance advocate Mary Ann Baker.

Marovich shared an early cylinder recording of the hymn during the Nov. 16 webinar. “That was a white quartet. At this point in time, the song really hadn’t entered the African American church,” he explained. “It was still pretty much a white Protestant hymn. … Between 1874 and probably 1920 was its great first wave. And then it just started to disappear.”

But the song began its re-emergence through arrangements and performances in Black churches and other venues in Los Angeles in the 1940s and 1950s, which eventually got the attention of Cleveland, a songwriter, arranger, singer and pioneer “of what you might call the modern choir recording movement,” Marovich said.

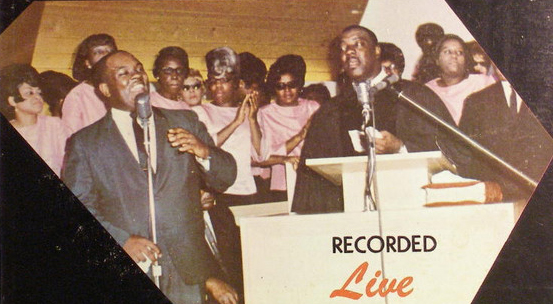

Cleveland, then under contract with Savoy Records, began recording live, in-service albums with the Angelic Choir at First Baptist Church in Nutley, N.J.

“This idea of hearing a gospel chorus in a church setting with congregations speaking back to the choir, and enjoying it, really was quite popular,” he said. “They had done two of these albums, and it came around time to do album three and the Rev. James Cleveland remembered ‘Peace Be Still’ from his days in Los Angeles.”

“This idea of hearing a gospel chorus in a church setting with congregations speaking back to the choir, and enjoying it, really was quite popular,” he said. “They had done two of these albums, and it came around time to do album three and the Rev. James Cleveland remembered ‘Peace Be Still’ from his days in Los Angeles.”

The Sept. 19, 1963, recording was an immediate and huge hit, Marovich said. “When people heard this song on the radio, they went crazy. They wanted to find this record. The phones rang off the hooks at the radio stations that were playing gospel music.”

The album would go on to sell up to 800,000 copies in an era when 50,000 copies was considered a hit for gospel recordings, he said. “By the end of the 1960s, it was still selling.”

The recording was entered into the Library of Congress National Recording Registry and into the Grammy Hall of Fame, Marovich added. “There were dozens and then hundreds of churches, a lot of choirs and a lot of other groups singing ‘Peace Be Still’ after that. So that album was sort of the watershed.”

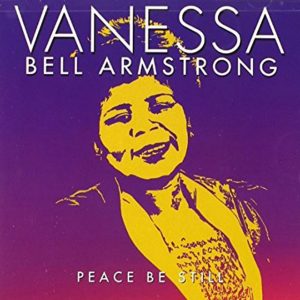

“Peace Be Still” made another high-profile emergence when singer Vanessa Bell Armstrong performed the hymn during the 1980s, he said. “She starts to do what a couple of other groups had done just before her, which was to talk more explicitly about having ‘peace in my home, peace on the job, peace of mind’ — bringing it more home personally than just kind of a general thought of ‘peace for my people.’ The Vanessa Bell Armstrong version is probably the best-known version now.”

“Peace Be Still” made another high-profile emergence when singer Vanessa Bell Armstrong performed the hymn during the 1980s, he said. “She starts to do what a couple of other groups had done just before her, which was to talk more explicitly about having ‘peace in my home, peace on the job, peace of mind’ — bringing it more home personally than just kind of a general thought of ‘peace for my people.’ The Vanessa Bell Armstrong version is probably the best-known version now.”

Marovich said he began his book project by contemplating why “Peace Be Still,” especially the 1963 version of it, became so wildly popular among Black Christians and churches. One theory was that Cleveland and the choir were moved deeply by the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Ala., which occurred four days before the recording.

Marovich said he ran that idea by surviving members of the choir. “They said absolutely not. They said, first of all, we’ve been rehearsing this song for days and days before that happened. They said we were only there to praise and worship the Lord. They said yes, we knew it happened. We were horrified by it. But it did not govern life.”

That response, Marovich said, convinced him “Peace Be Still’ was not a protest song like many others being sung at that time. “It was not a song associated at all with the movement. It was not a song that was sung on the protest lines or anything like that.”

Yet it was a hymn sung to express the need for, and confidence in, God’s power to face life challenges, no matter how bleak.

“Members of the choir had their own local issues,” he explained. “Newark, N.J., in 1963 had its own issues. A little bit before this recording took place, there was a drive-by shooting near Newark where a group of white boys shot a Black girl on her porch and killed her. There was poor housing, there was discrimination and just the daily indignities of life growing up African American in 1963. The sense that I got, in terms of what the song meant to the choir, was of making sense of a social order that doesn’t make sense to begin with.”

Even so, Marovich said it’s likely the hymn evoked thoughts of Civil Rights protest and lament for some of its wider audience. “I am guessing that for some people who listened to ‘Peace Be Still,’ it maybe did conjure up images of the Birmingham bombing and the many other things that happened in 1963.”

He added that the recording was released in October that year. “We’ve got to remember in November, when this album was brand new … it was just before the assassination of President Kennedy. The song may have had a message there in terms of overcoming. As I mentioned, it was played at a president’s funeral (in 1881), so I’m sure there are people who sort of made that connection as well.”

Adam Bond

Marovich, his book and its subjects highlight the spiritual and cultural contributions of Black artists to the church, said Adam Bond, pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Richmond, Va., which hosted the webinar.

“It is important that we do not take for granted the genius of the musicians and the choirs, the congregations and their artistic contributions to worship in terms of pulling it together to inspire our souls, to provide us with the melodies that have made us tap our feet and clap our hands, and the lyrics that have provided us moments of deep reflection,” he said. “We know that Black sacred music has given us soul-stirring sounds that have carried us through the highs and lows of our existence.

“Accounts such as the ones in this book, as we think about what it means to be Baptists, as we think about what it means to tell our story, and as we think about the ways in which our faith has moved the world in the right direction.”

But the musicians and music discussed in the book also illuminate the important contributions of Baptists, Bond added. “It is also Baptist history. It is a religious history that helps us to understand how rich the story is of so many local congregations and the people who are formed within them who go on to influence culture in their unique and authentic special ways.”

Related articles:

Baylor’s Black Gospel Archive and Listening Center now open to the public

Baylor professor’s quest to preserve golden age of black gospel lands in Smithsonian