The message of Thomas Helwys — a founder of the Baptist denomination and one of the first Englishmen to state explicitly that people of any religion should be free to exercise their faith without government interference — is as relevant today as it was in 1616, according to speakers at a recent event commemorating the 400th anniversary of his death.

“Thomas Helwys is rightly regarded as the pioneer Baptist leader,” Tony Peck, general secretary of the European Baptist Federation, said in a keynote address at a recent gathering at The Well, also known as Retford Baptist Church, near the Nottinghamshire village where Helwys probably was born. The church was organized around 1691.

Peck said a core value of the approximately 100 million Baptists living today around the world remains “a Baptist contribution to building a peaceful and tolerant society.”

“That is a commitment to religious freedom for all, not just for ourselves,” Peck said. “We owe that to the legacy of Thomas Helwys, even if we have not always lived up to the full extent of his vision.”

Born into a family of some reputation — his uncle served as sheriff of London and his cousin was knighted by the king — Helwys became associated with the early Puritans, a group of dissenters from the Church of England. He developed a close bond with dissenter John Smyth, and he and his wife became members of Smyth’s separatist congregation in Gainsborough.

Church authorities cracked down on the dissenters, and about 40 members from Gainsborough and another congregation fled to safety in Amsterdam in the more tolerant Dutch Republic. While there Smyth became convinced that baptism should be for Christian believers instead of infants, marking the birth of the earliest church labeled “Baptist” in 1609.

Smyth later embraced Mennonite doctrines, while Helwys and others began working on the earliest Baptist confession of faith. Helwys returned to England to start a Baptist church, an act that was still illegal, and it became the first congregation of the Baptist denomination in England. Before he left Helwys completed A Short Declaration of the Mistery of Iniquity, the first book in English making the case for universal religious freedom for all faiths and for those with no faith at all.

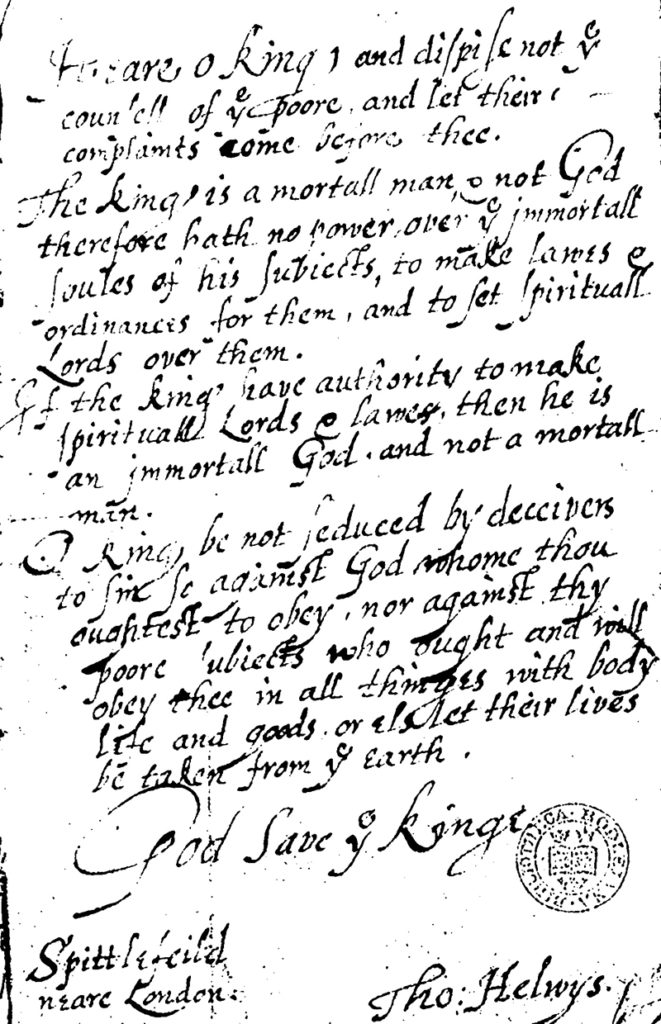

“The King is a mortal man and not God,” Helwys wrote. “Therefore he has no power over the immortal souls of his subjects, to make laws and ordinances for them and set spiritual lords [bishops] over them. If the king has authority to make spiritual Lord and laws, then he is an immortal god and not a mortal man.”

It is unclear if King James I, who commissioned the Authorized Version of the Bible published in 1611, read Helwys’ words, but somebody did, landing the Baptist in Newgate Prison, where he died probably around 1615 or 1616.

Peck said Helwys’ unconventional views probably resulted from his interaction in Amsterdam with Dutch Anabaptists, the radicals of the Reformation whose teaching embraced universal religious freedom. “Nobody was putting forward such a bold vision at that time in England,” Peck said.

Peck said it took about three decades for Helwys’ ideas to find a more ready audience in England. From there Helwys’ ideas directly influenced Roger Williams, who founded an American colony based on religious freedom in Providence, R.I., establishing ideas of religious liberty later enshrined in the U.S. Constitution.

Peck said it took about three decades for Helwys’ ideas to find a more ready audience in England. From there Helwys’ ideas directly influenced Roger Williams, who founded an American colony based on religious freedom in Providence, R.I., establishing ideas of religious liberty later enshrined in the U.S. Constitution.

Peck said the religious and political strife Helwys experienced during his lifetime caused him to believe his generation was living in the last times. In many ways his book “calls out a pure church to be ready for the final apocalypse,” Peck said. Attacking every other church in England, Peck said by today’s standards “Thomas Helwys does not come across as a very tolerant man.”

In the middle of his polemic, however, Peck said there emerges a “pure diamond,” the book’s most famous passage: “For our Lord the King is but an earthly king, and he has no authority as a king in earthly causes. And if the king’s people be obedient and true subjects, obeying all human laws, our lord the king can require no more. For men’s religion to God is between God and themselves. The king shall not answer for it. Neither may the King judge between God and men. Let them be heretics, Jews or whatsoever, it appertains not to the earthly power to punish them in the least measure.”

Though it didn’t go over well at the time, Peck said it is important to note that Helwys went out of his way to stress loyalty to the king in “everything except the individual conscience regarding religion and spiritual matters,” at one point urging non-conformists like himself to be prepared to fight in battle for the king if the nation is threatened.

Peck said Helwys’ argument for religious freedom was not the later idea of inalienable rights that would give rise to the French and American revolutions.

“Helwys’ conviction was rooted in his Christian faith; that if Jesus Christ is King and Lord, then he is especially Lord of the spirit and the conscience and there can be no other kings, no other lords that get in the way of the free response of faith on the part of the individual,” Peck said. “In the realm of the spirit, the earthly King cannot play God, though he is to be obeyed in everything else.”

Whether or not he knew it at the time, Peck said, Helwys “was articulating a bold vision of a plural society that values and protects its minorities at a time when everyone was religious and atheism was almost unheard of.”

“It was a blueprint for a very different kind of society a long way from the reality of its time,” Peck said. It’s a message, Peck said, that especially resonates today.

“So the legacy of Thomas Helwys, richly nurtured in the fertile spiritual soil here on the borders of Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire, lives on in a very different English society but one that still faces urgent questions about how those with different faith convictions and none are to live together in peace,” Peck said. “May his bold vision continue to inspire us, too.”