Last week Baylor University, the world’s largest historically Baptist university, released a study revealing the slaveholding and Confederacy elements of its history. The report, commissioned by the Baylor board of regents, considered the stories of Baylor’s founders and those memorialized in its public spaces.

Like Georgetown University, the University of the South and other antebellum universities, there is much at Baylor to recognize and much to repent, and one administrator told me that this report was long overdue. But some observers concluded that the changes recommended in the report did not go far enough, while other people condemned the entire enterprise as an attempt at “cancel culture.”

Greg Garrett

As a Baylor faculty member who has been calling for this reckoning for some time, I find myself squarely in support of the report. In a world where our histories, rituals and shared stories need to be examined, this document does so in a rigorous and detailed way, with sources and resources that will teach you as much as you care to learn.

Maybe it doesn’t go quite far enough. But it does represent a solid step forward, and it helps us reckon with Baylor’s past, present and future. I’ll personally be using the commission’s report in my own writing, speaking, teaching and preaching about race and how we work toward reconciliation.

Baylor’s past is our nation’s past. Built on the paradox of high democratic ideals that did not initially extend to all people, Baylor nonetheless has transformed hundreds of thousands of students in the 176 years since its founding. We have trained doctors, lawyers, teachers, preachers — and every other kind of person — then sent them into the world and imbued in them an ethic for service. That is an absolute good.

But when we hold our past up to the light, look at Baylor’s founders, first board and most important president, Rufus Burleson, there is much to lament.

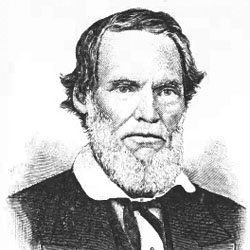

R.E.B. Baylor

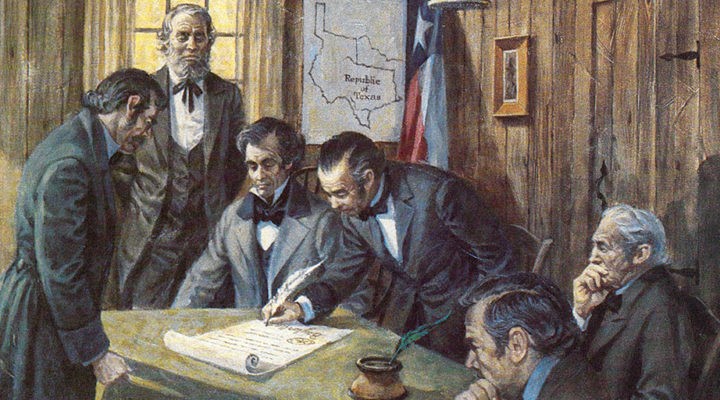

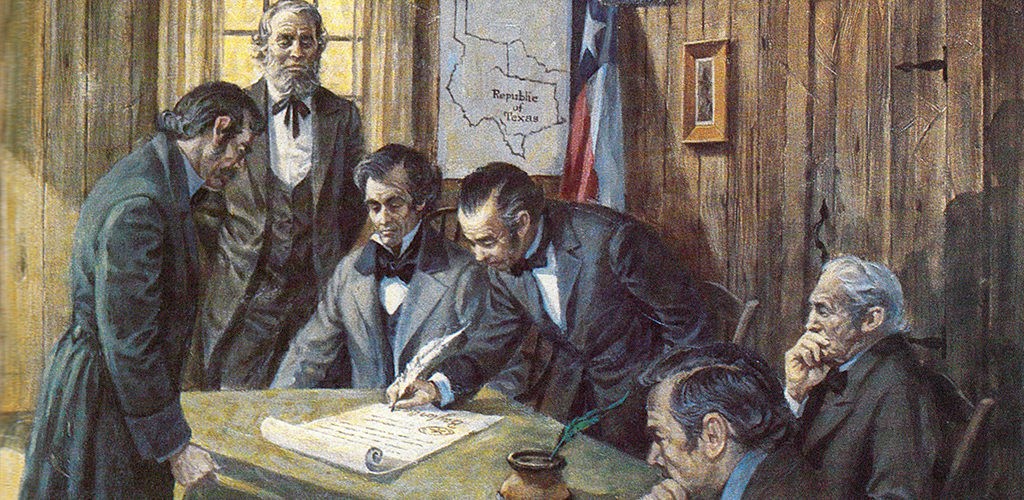

All of Baylor’s founders, including Judge R.E.B. Baylor, were slaveholders. Baylor’s initial campus at Washington on the Brazos was built using slave labor. Judge Baylor, one of the wealthiest men in Washington County, owned more than 30 slaves and, perhaps just as significantly, presided over a number of trials with shattering outcomes.

As A. Christian Van Gorder notes in the Waco Tribune-Herald: “In fulfilling his duties as a judge, Judge Baylor presided over cases that resulted in the punishment of an abolitionist harboring an escaped slave, the punishment of a man for not returning a borrowed slave promptly, the sentencing of a slave to hang for arson, the execution of another slave in 1856, and the execution of a slave for ‘intent to rape a white female.’”

All this is heinous. The namesake of my university was a slaveowner who believed ardently in the institution of slavery and in white supremacy.

But admitting this truth — and lamenting it — is an essential part of our recovery from the past. In the Christian tradition, we admit our wrongs, amend our lives, ask forgiveness from those we have wronged, and seek to repair those relationships. I think this report is a solid beginning to that work.

Over the last year, I’ve read social media posts from activists who wanted Baylor to change its name, or to give away its endowment to good causes. Neither of those actions are in service to the startlingly multicultural student body we now serve, and no one will come to Waco to enroll at “Big Baptist University.”

But to tell the truth about our racist past? That is a radical witness in a society that admits the truth less and less often about things of which we should rightly be ashamed.

“To say that Baylor was founded by white supremacists and racists is to admit that they exist.”

This truth telling also could make a difference in the present. To say that Baylor was founded by white supremacists and racists is to admit that they exist, and to lament that history is to condemn them.

Our present — both in America and at Baylor — is more racially fraught than at any moment in my life. On the day after the 2016 general election, for example, a white male Baylor student shoved a Black female student to the ground. Uttering a hateful racial epithet, he told her that people like her were no longer allowed to use the sidewalk and explained to outraged bystanders that he was just “making America great again.” Other racial incidents, rare but nonetheless painful, have followed at Baylor.

The casual and unhidden racism of President Donald Trump (whom Ta-Nehesi Coates called “the first white president” in The Atlantic), has contributed to hate crimes of all sorts since he descended that escalator in Trump Tower in 2015 to decry the “drug dealers, criminals, rapists” that Mexico was sending us. The Southern Poverty Law Center has mapped startling rises in hate crimes and in the ascendance of white supremacist groups, which culminated, of course, with white Christian nationalists waving the Confederate battle flag inside the embattled United States Capitol Jan. 6.

The past president helped to normalize racial hate; a reconciliation process that properly laments our racist history could help to restore some moral guardrails.

“A reconciliation process that properly laments our racist history could help to restore some moral guardrails.”

Calling out our past — and those white Christian men who employed the Bible to justify slaveholding and the Lost Cause — might also help Baylor reckon with our future. Like every American Christian denomination, Baptists are wrestling with sexual difference and with LGBTQ issues. Baylor has not yet been able to strike a liberatory stance on such things as gay, lesbian and trans people because of our multitude of constituencies, and because of biblical passages about homosexuality.

But what the theological debate on slavery — and on the role of women — could teach us is that it is essentially unchristian to employ the Bible to suggest that any of God’s children are anything less than fully loved, fully seen and fully human. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin depicts a debate between a pastor quoting chapter and verse from the Bible to support slavery and another pastor suggesting that the controlling narrative of the Bible is about God’s love for all of humanity, a debate that Mark Noll records happened multiple times in the run up to the Civil War.

The Bible is our record of God’s continuous longing for us. All of us. Biblical proof-texters were wrong about slavery. They were wrong about women in the church. And they are wrong about my siblings who do not love or identify as I do. Admitting that we were wrong about these past biblical debates could lead us in the direction of Christian love in the latest one.

Baylor is an imperfect human institution that I have served for more than 30 years; I am at once realistic and hopeful about our progress. And I am grateful for this report and the work of the commission, and I pray it will bear good fruit.

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. One of his most recent nonfiction books is In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett. His latest book, A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation, is hot off the presses. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

3 words for the church in 2019: ‘we were wrong’ | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Tearing down statues doesn’t erase history | Opinion by Ella Wall Prichard

Baylor not yet where it wants to be on race, Livingstone tells forum