The way a group of 19th-century Baptists covered up a sexual assault committed by one of their own testifies all too clearly about the misuse of privilege and power when protecting beloved institutions, according to the authors of Remembering Antônia Teixeira: A Story of Missions, Violence, and Institutional Hypocrisy.

The new book and its authors, Baylor scholars Mikeal Parsons and João Chaves, were the focus of a Aug. 30 webinar hosted by Baptist News Global and moderated by Mark Wingfield, BNG executive director and publisher.

The new book and its authors, Baylor scholars Mikeal Parsons and João Chaves, were the focus of a Aug. 30 webinar hosted by Baptist News Global and moderated by Mark Wingfield, BNG executive director and publisher.

In documenting the late 19th century rape of a Brazilian girl in the backyard of Baylor University President Rufus Burleson, the book calls attention to the pressure Christians often feel to protect the image and reputations of churches, ministries and other institutions — even when it seriously hurts others, the authors said.

Joao Chaves

“It is a graphic reminder that institutional mythmaking is often at odds with care for vulnerable people, and we need to pay attention to that,” said Chaves, an assistant professor of the history of religion in the Americas.

“There’s always a tension to do what we think is best for the institution,” added Parsons, a professor of religion. “But sometimes we do what we think is best for the institution in harmful ways to those who are most vulnerable among us. That’s a constant challenge to us.”

The book presents a graphic account of the 1894 rape of Antônia Teixeira by Steen Morris, who assaulted the young woman from Brazil multiple times in the backyard of Burleson’s Waco home. Morris was the brother of Burleson’s son-in-law.

Parsons and Chaves also document the scandal and trials that occurred when Teixeira’s resulting pregnancy became public, as well as the campaign of victim shaming, intimidation and cover-up waged by Burleson and other Baptist leaders to protect the image of Baylor and Southern Baptist mission work in Brazil. The authors said they had to go back more than a century to strip away decades of misinformation and secrets that shrouded the case.

The back story

The back story begins with the high-profile and scandalous life and ministry of Teixeira’s father, Antônio, a Catholic priest who kidnaps a 17-year-old girl whom he eventually marries. “He is framed as this archetype of Catholic corruption because of this national debate” occurring between church and government leaders at the time, Chaves said.

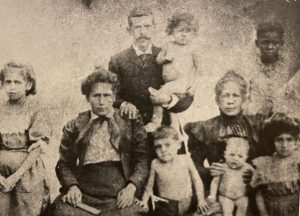

Portrait believed to be of Antonio Teixeira de Albuquerque and family around 1882.

Antônio Tiexeira subsequently abandons Catholicism and becomes a Baptist pastor. He is embraced by Southern Baptist missionaries who are impressed with his ability to preach and write in multiple languages. He becomes the first native-born Southern Baptist missionary in Brazil.

But he continues to be a lightning rod of controversy, with Catholics saying he converted only to be able to marry his kidnap victim. “So, it’s a character flaw that he has, not a theological distinction,” Chaves said. “The Protestant account is that he read the Bible and he believed the Bible and that led him to become a Baptist.”

Antônio Tiexeira endears himself further with his Baptist proponents by publishing a leaflet, “Three Reasons I Left the Roman Catholic Church,” Chaves said. “He becomes this very skilled polemicist and a representation of the superiority of Protestantism over Roman Catholicism.”

Key supporters of the man included legendary Southern Baptist missionaries William Buck Bagby and Zachary Taylor. The former priest helps the two leaders acclimate to their new surroundings as they help expose him to the enclaves of former Confederates who had immigrated to Brazil after the U.S. Civil War and hoped to perpetuate the Lost Cause.

Racism and anti-Catholic sentiment

Antônio Teixeira’s “whiteness” —as it was defined in Brazilian society — also helped him navigate Southern Baptist circles, Chaves said. “Southern Baptist missionaries could not imagine Antonio as white in their racial spectrum” but they still considered him closer to European heritage than darker-skinned Brazilians. As a result, the former priest “was considered differently and more positively than many other Brazilians were by the missionaries.”

Miikeal Parsons

Racism predated the missionary movement in Brazil, he added. “The missionaries certainly had racial biases and imagined race differently. But we do not want to suggest that they exported racism to Brazil. Brazil was already a deeply racist society. As a matter of fact, part of the attraction for former Confederates to go to Brazil was that Brazil was a slaveholding country until 1888.”

Antônio Teixeira’s status as a former priest also made him useful to Baptists in a country where Catholic-Protestant tensions ran high, Chaves said. “Being a Catholic priest who left the priesthood makes him a kind of poster child for the Protestants and especially the Baptists. That also means he’s probably better educated than the Baptist missionaries because he’s been to seminary, he knows the languages, et cetera.”

Wingfield said the portrayal of missionaries contained in Remembering Antônia Teixeira differs greatly from the stories he learned growing up Southern Baptist. “A lot of good happened, but it turns out the motive wasn’t always as pure as the gospel itself.”

“We are always negotiating our human dispositions with the higher aspirations of the gospel message.”

Chaves responded that the standards set in Scripture often are filtered through culture in their implementation. “We are always negotiating our human dispositions with the higher aspirations of the gospel message. “

Brought to Texas

And that is precisely what unfolded after Antônio Tiexeira died in 1887 and his family fell into poverty. Antonia, his eldest daughter, accompanied Taylor and his family to the United States. Later, the missionary wrote to Burleson asking that the girl be allowed to enroll at Baylor Academy, Parsons said.

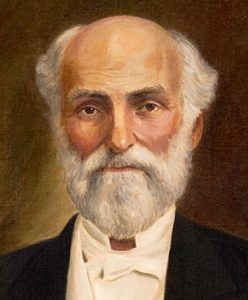

Rufus Burleson

“And Burleson allowed her to come. She lived in the Burleson household in exchange for going to classes. She was basically the housekeeper. And after she was there for two years, she took fewer and fewer classes and spent more and more time doing housekeeping.”

It was on a November evening in 1894 when the Burlesons and many others in Waco attended the opening of the Cotton Palace, a grand exhibition hall celebrating the region’s cotton-growing industry. Around 9 p.m., Steen Morris knocked on the back door to the kitchen and asked Teixeira to step into the backyard, Parsons shared from trial testimony.

“When I refused to, he then took me by the arm and pulled me out. He threw me on the ground and got on top of me. He said, when he dragged me out there, he was not going to hurt me,” the woman testified.

Georgia Jenkins Burleson

But she was, in fact, hurt during the rape and in two subsequent assaults by Morris in November and December that year. She reported the attacks to Burleson’s wife, Georgia, who later denied knowing of the incidents.

The trials

“A reporter saw her in the spring of 1895 and saw that she was pregnant and interviewed her. And so, this story broke,” Parsons said. “It wasn’t that Antônia was trying to bring the story to the surface. She was interviewed. Burleson was also interviewed as part of this newspaper report. Steen Morris was arrested.”

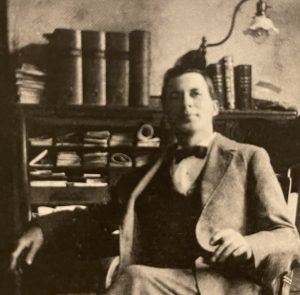

The first trial ended when Morris’ attorney convinced a judge to dismiss the case, but the issue was revived when firebrand journalist William Cowper Brann took an interest, Parsons said. “He began criticizing the reaction of Burleson and Baylor for not protecting Antônia, and for being more concerned about the institution. Burleson was in a pickle. This is his son-in-law’s brother, and this happens in his back yard. This is where all three assaults occur.”

Burleson hit back with “The Brazilian Girl and Baylor University,” a pamphlet that victim-shames the girl and blames the situation on a Brazilian trait for telling lies and being unable to control their passions, Parsons said.

“And now this story gets picked up throughout Texas and becomes the scandal of the decade if not of several decades. And the Galveston paper — Galveston was a huge city at that time — is reporting this and keeping the story going, and so Steen Morris is rearrested and actually put on trial,” Parsons continued.

William Cowper Brann

The Burleson family doctor testified that Teixeira is “probably very promiscuous” and that the father of the baby is unknown. Another physician who examined her confirmed she had suffered unhealed lacerations consistent with sexual assault.

“We had two forensic medical doctors who testify in cases here examine (the testimony) and they agreed that it clearly suggested that Antônia was a victim of some kind of sexual assault,” Parsons said. “It doesn’t mean that it was Steen, but nobody else was ever implicated.”

The trial ended in a hung jury and was rescheduled for 1896, but then Teixeira, who had given birth prematurely to a child that died less than a year later, signed an affidavit recanting her testimony. “And the next day she’s on a train and has left town. We lost her trail at that point,” Parsons said.

Burying bodies and the story

But there were consequences for Burleson and Baylor, especially after Brann published articles warning Americans against sending their daughters to the Waco school. “Burleson himself is going to step down from the presidency, perhaps partly because of his involvement in this — not necessarily because he didn’t do the right thing by Antônia, but because he couldn’t handle Brann’s criticism,” Parsons said.

Additional fallout from the scandal came in the form of gun duels that killed a Waco newspaper editor and his brother, and then Brann died in a shootout in which he and his assailant, a Baylor supporter, both were killed.

The reaction of other Baylor supporters was to seek ways to ensure the story was buried and forgotten,” Parsons said. “The intention was to preserve this notion of institutional goodness. In order to do that, they really have to scandalize Antônia. And so she’s left, as Brann says, with all the church people protecting Baylor, and it’s all the skeptics and unbelievers who put their money together to provide a defense for Antônia.”

“The intention was to preserve this notion of institutional goodness. In order to do that, they really have to scandalize Antônia.”

The authors found other evidence of the coverup, including efforts to omit Teixeira from writings. “Interestingly, when Zachary Taylor writes his autobiography, he never mentions that Antônia was with them (on the trip to the U.S.). But we have the ship manifest that lists her as a servant.”

Her father’s official biography, meanwhile, does not name his eldest daughter, Chaves added. The author “just calls her ‘firstborn.’”

Despite the mythmaking perpetuated by Burleson and other Baptists and civic leaders in Waco, today’s Baylor University administration actually made the research behind the book possible.

“The impetus for the book began at the invitation of President Linda Livingstone after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. A lot of institutions began institutional reckoning with their entanglements with race relations and, in the case of Baylor, with chattel slavery and its origins,” Parsons said. “We would like to think that when the decision was made to rename Burleson Quadrangle and to move the statue of Rufus Burleson to a less prominent place, that this might have contributed to that in some way.”

Parsons and Chaves thanked Livingstone for providing encouragement and grant dollars to make Remembering Antônia Teixeira possible.

Watch the video of the webinar here.

Related articles:

Co-chairs of Baylor commission on historic representations say their research was distressing

Alumni applaud Baylor University’s pledge to explore racist roots

Tearing down statues doesn’t erase history | Opinion by Ella Wall Prichard