Note: This is the third in a five-part series on the Black Gospel Music Preservation Program made possible by generous funding from the Prichard Family Foundation.

Most puzzles and riddles are simply good fun, but sometimes they provide important information to those solving the puzzles. In the case of Black gospel music, however, the information sometimes was a matter of life and death.

Discovering hidden messages in recorded music has been one of the unexpected surprises of Baylor University’s Black Gospel Music Preservation Program. Launched in 2006 by journalism professor Robert Darden, the program encompasses the world’s largest initiative to identify, acquire, digitize, catalog and make available America’s fast-vanishing legacy of vinyl records from the “golden age” of gospel music — roughly 1945 to 1975.

Darden, who retired in May with the title of professor emeritus, said Baylor researchers were aware some recordings had what historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. calls a “double voicedness,” particularly the 45s of the early 1960s, but they didn’t realize there were so many records produced that way.

“As the 45s began coming in for the first time, we began looking on the B side and seeing a significant percentage of the songs were civil rights related,” he said. “Nobody knew that because nobody had that many. And that’s what set me on that long journey to those two books.”

Darden was referring to Nothing But Love in God’s Water, his two-volume history and exploration of the power of Black sacred music from slavery through the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. The books were published in 2014 and 2016 by Penn State University Press.

Darden was referring to Nothing But Love in God’s Water, his two-volume history and exploration of the power of Black sacred music from slavery through the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. The books were published in 2014 and 2016 by Penn State University Press.

Darden said a prime example of the messages hidden on the B sides of 45s comes from Dorothy Love Coates, a gospel artist from Birmingham, who with the Harmonettes in the early 1960s employed this method to communicate to those working for justice and equality.

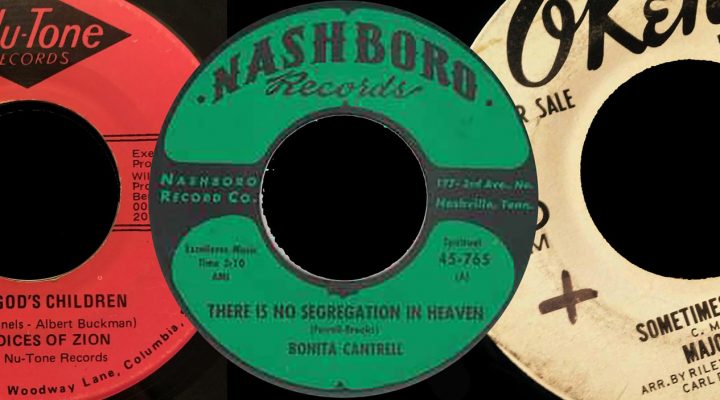

“You could be a little 18-year-old Black youth walking through the most dangerous city in America where they were bombing churches every night,” he said, “and you would have a 45 that on one side would say, ‘Glory, Hallelujah,’ but if you turned it over, the secret side that white people wouldn’t know and radio wouldn’t play, it would say, ‘I Believe Dr. King is Right’ or ‘We Shall Overcome’ or my favorite, ‘Ain’t No Segregation in Heaven.’ So, it’s in broad daylight and yet there’s the subversiveness of it.”

Darden said this practice communicated messages of hope and perseverance across state lines at a time when Blacks had no agency with traditional media outlets.

“If you don’t control the newspapers, radio or anything, how do you know that there’s other people in the country and you’re not alone?” he said. “Well, buy The Friendly Four Quartet, and the flip side is ‘Where Is Freedom?’ which name-checks all the cities where Civil Rights movements are taking place, who the leaders are and who the bad guys are. And the information is being shared right under the noses of the oppressors.”

An unbroken tradition

As remarkable as the hidden music may seem, Darden said it’s actually a modern take on what Black slaves were doing 100 years earlier.

Baylor University professor Robert Darden (right) with Henry Louis Gates, creator of the PBS documentary, “The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song.” Photo: Mary Landon Darden

“It’s an unbroken tradition, apostolic from the protest spirituals,” he said. “Have you ever heard one called ‘Follow the Drinking Gourd’? It’s an obscure one, but it is an actual road map from the plantations of the Tombigbee River (in Alabama) to get across the Ohio (River).”

Another example is the better known “Wade in the Water,” which Darden said answers the question: Where do you go so the dogs can’t follow you?

“How stupid of an overseer do you have to be not to know that the song, ‘If the Lord Delivered Daniel, Why Not Any Man,’ is a dangerous song?” Darden said. “Or ‘Steal Away to Jesus.’ There’s 6,000 known spirituals, but what percentage of them had this double-voicedness? Maybe all of them.”

Darden said there’s not a clear sense of how much recorded music is still out there that hasn’t been uncovered. An example is the Pilgrim Travelers, a group from Houston, who released 15 to 20 LPs during gospel music’s golden age. The record company that owns their label has released two albums of their greatest hits, but the other tracks they recorded are unknown.

“None of their other stuff is available,” Darden said. “There is no way for me to even get the names of the remaining 13 albums unless they show up here, or we find them in (research for) a new book we’re working on. And they were one of the biggest acts of their day.”

Salvation in the grooves

Stephen Newby, formerly at Seattle Pacific University and now the inaugural Lev H. Prichard III Chair in the Study of Black Worship at Baylor, said the spirituals weren’t just about freedom but salvation as well.

“You can’t ignore they were about freedom in the North. There were hidden codes in the music,” he said. “But they were also about life — how we wanted to live better — and we hear the same thing in the gospel music today.”

Stephen Newby

For example, he said, when Hezekiah Walker sings, “I Need You to Survive,” with the words, “I need you, you need me,” it’s not about the end times.

“It’s about things that are going on right now,” he said. “It’s not just about the life after; I want you to survive now so that you can thrive in the kingdom. No, I want you to survive so you can thrive and you can flourish right now. And how heaven can become part of earth right now. That’s the gospel message, and everyone needs the gospel message.”

Newby said he wouldn’t categorize the music as “evangelistic.”

“I would just say it’s sharing who Jesus is,” he said. “Jesus was the name that brought our people through. After they came through the Middle Passage and landed on the shores of the Americas, it got them through the devastation and the demoralization of life.”

The gospel message is for all people, but gospel music is a genre anchored in the African American community, Newby said.

“Because of that rite of passage, they had the right to this music, because they are the progenitors,” he explained. “They’re the co-creators of the music with the original creator, God, the wise Creator of all things, and that’s the way Black folks look at this. We’re co-creators with God. But God has given this incredible treasure to this people group so that it might be shared with the world.”

The Black Gospel Music Preservation Program encompasses 5,000 vinyl records on the shelves and 48,000 digitized tracks. The program also is home to the Black Gospel Preachers Project, a growing archive of hundreds of hours of sermons, many by the historic greats of Black gospel preaching. The collections are accessible in person through a state-of-the-art listening center at Baylor’s Moody Memorial Library. Digitized recordings may be heard from anywhere via the library’s online digital collection.

Related articles in this series:

Around the world and back: The enduring influence of Black gospel music

Black Gospel Music Preservation Program: Securing the legacy of Black Gospel music