Note: This is the last in a five-part series on the Black Gospel Music Preservation Program made possible by generous funding from the Prichard Family Foundation.

While Baylor University’s Black Gospel Music Preservation Program is all about the music, where it came from and what it means, behind the scenes it offers a glimpse of how universities and other institutions can build an archive of historical artifacts or documents that not only attract scholarship and cultural tourism but funding and resources for other projects.

“Every university could do this for a relatively small outlay of money, if you’ve already got a collector or somebody who has something — a faculty member or alumni or someone,” said Robert Darden, professor emeritus who founded the Black gospel music collection in 2006 and was its guiding hand until his retirement in May 2023.

The Black gospel music collection is one of more than 70 digital collections maintained by Baylor Libraries. Among them, the Baker Sheet Music Collection is the largest of its kind in the country, while the Institute for Oral History is the second largest after Columbia University.

“All those things have benefited the university, both from a scholarly and attention standpoint,” he said. “And driving not just scholars here, but money here and people’s collections.”

Technology vital to preservation

While the donation and loan of rare recordings has been essential to the development of the Black Gospel Music Preservation Program, so has been the acquisition of technology, staff and space to preserve the recordings. It’s been an incremental process that has benefited not only the gospel program but the entire university library system.

Darryl Stuhr

Darryl Stuhr, director for Digitization and Digital Preservation Services in the Library and Academic Technology Services Group, said Baylor’s digitization initiative began in 1999 with limited resources. The first project was the Spencer Sheet Music Collection, an archive of 28,000 pieces of American popular sheet music, followed by materials from the Armstrong Browning Library and the Dawson Institute of Church-State Studies. Then in 2006, he was approached by Darden about the Black gospel music program.

“When he told us about it, we said, ‘Well, this sounds great, but we’re going to need all this,’ and we slid some paperwork across the table, which was a decent amount of money,” Stuhr said. “We wanted an audio engineer because we didn’t have that experience, and we wanted a media librarian who could come in, set the schema for the collection and begin cataloging all of this stuff.”

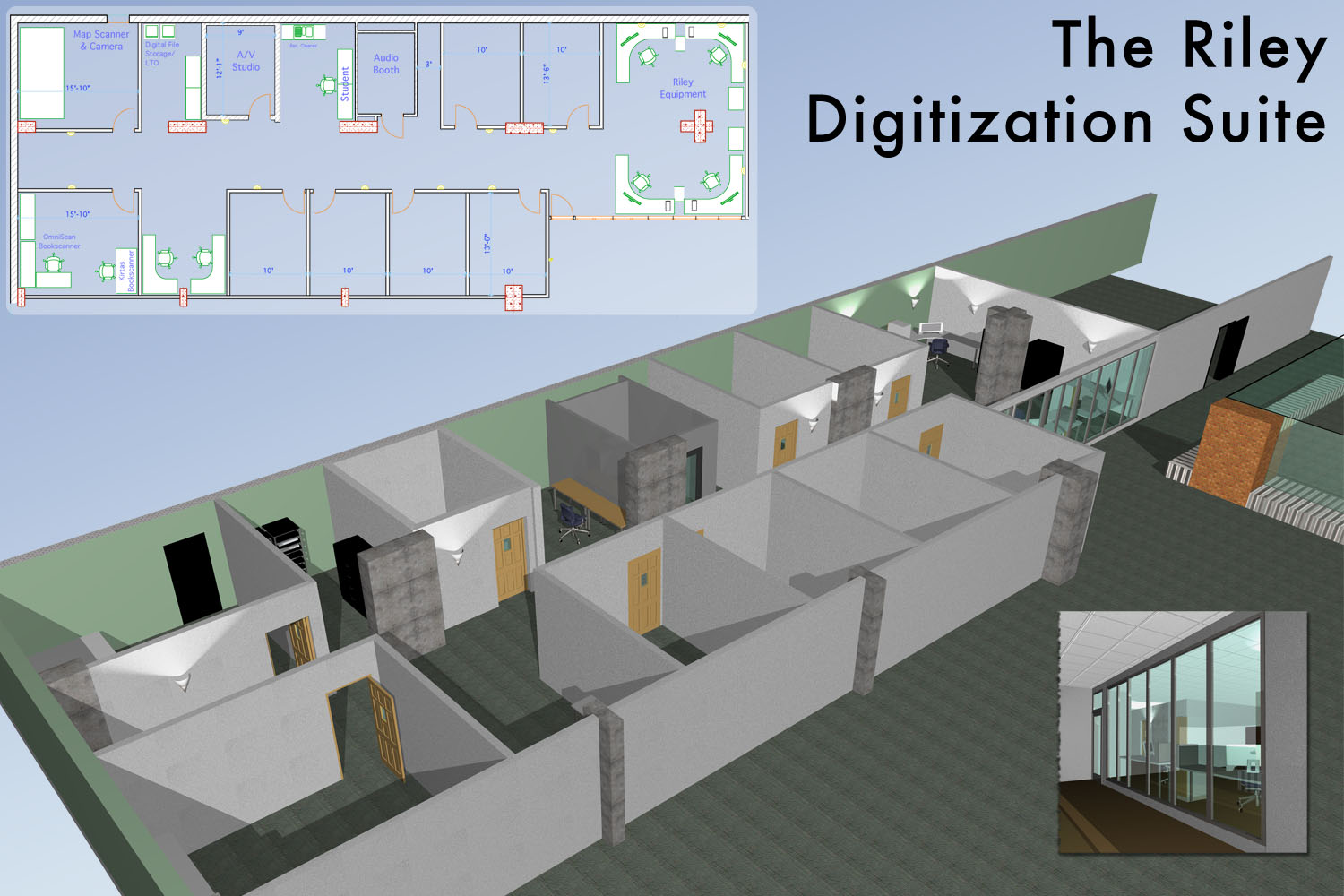

With financial help from the university, foundations and donors, the digitization program moved from four workstations in 400 square feet on the third floor of Baylor’s main library to a full suite of space on the garden level in 2008. Along the way, an impressive array of the technology required to digitize and preserve materials has been acquired: an audio sound booth with Rega and Technics turntables for analog disc migration; various Zeutschel format scanners; a Kirtas KABIS 3 high-speed book imager; a Cruse large format scanner; an InoTec Scamax 400-Series high speed document scanner; decks for the digitization of Umatics, Betamax, DATS and VHS tapes; a cassette transfer system; a Filmfabriek HDS+ 8mm and 16mm film scanner; and a Sony Alpha 7R III mobile camera scanning system.

“It was the gospel project that really helped push us and allowed us to create this space,” Stuhr said, and that has been a boon for the more than 70 digital collections archived and managed by the group. Those collections encompass maps, 19th century letters and books, sheet music, analog sound discs, cassette tapes, photos, speeches, videotapes, newspapers, yearbooks, posters, architectural blueprints and oral histories.

As well, the small staff of part-time undergraduate and graduate students, some coming out of Baylor’s Museum Studies program, that began digitizing collections and helped launch the Black Gospel Music Preservation Program is now a full-time staff of experienced technicians and media preservationists.

The fine art of preservation

When a vinyl record comes into the digital preservation center, it’s cleaned, digitized, photographed and catalogued into the digital archive. If donated, it’s added to the shelved collection; if loaned, it’s returned to its owner.

“A lot of the records are in pretty rough shape. A lot of them are going to be warped and moldy,” Stuhr explained.

To get them ready for digitization, records are washed in a machine that applies a solution made with distilled water into the grooves with brushes and then vacuums them dry. The process is repeated with soda water to remove any soap residue, and then the record is vacuumed again.

Records in better shape go into an automatic de-gritter machine that cleans the grooves with ultrasonic pulsations.

Riley Digitization Center

Once cleaned, the record goes onto a high-tech turntable where it is digitized at real-time speed for best quality, and the record and label are photographed at high resolution. The recording is captured with Metric Halo software and saved as an uncompressed WAV file. Another program called WavLab divides an LP recording into tracks and metadata information is added. Another program, iZotope, eliminates clicks and pops and converts the files into MP3 audio files. The MP3s are added to the digital collection, and the preservation files are saved onto a preservation server.

“That way if we ever need to go back and redo them for some reason or touch them up, we can go back to that complete raw file,” Stuhr said.

A fair amount of gospel recordings have come to the program on cassettes, and the archive has machines to duplicate and digitize those. As well, some of the preaching recordings and oral histories are on reel-to-reel tapes, and those are digitized too.

“We don’t do cylinders, but if we ever got some, we would figure out a way to do them or we might have to outsource them,” Stuhr noted.

The only other format that has yet to come into the program is eight-track tapes, but Darden said they were so widely commercially available that most of the music has been re-released into digital music stores.

Another related project under way is updating and restructuring the “Hayes & Laughton Gospel Discography,” an out-of-print discography of gospel music recorded from 1943 to 1970. At Baylor, the document is being retyped and restructured into what will be a searchable, relational database of performers, albums and track titles.

Metric Halo in Baylor’s Digitization Center

“Then we can start doing these incredibly complex searches where you can say, ‘I want the names of quartets in the 1960s from Philadelphia,’ and there’s your list,” Stuhr said. “And then it gets better because we will link that list to our digital collection if we have that audio file.”

Darden said of the 48,000 digitized tracks, roughly 20%, mostly post-1980, are commercially available in digital music stores like Apple Music, Amazon and Spotify. Those albums and tracks are locked down for on-campus access only. Anyone off-campus searching the online database will still be able to see them in the collection — the labels and cover images and the metadata — but they won’t be able to access the audio file.

As well, the online portal has messages informing copyright holders that if they come across something they own, they can contact the program and the music will be taken down if desired. The collection has been online for two years and they’ve yet to receive a takedown request.

For students and scholars on campus, researching and even just enjoying Black gospel music is a hands-on experience at the listening center that opened in November 2021 on the garden level of Baylor’s Moody Library. The centerpiece of the space is a Framery brand sound isolation pod with high-end audio equipment and a full keyboard for researchers who want to play along with sheet music or recordings from the collection.

Related articles in this series:

Bridging racial divides with Black gospel music

Black gospel music has messages hidden in the grooves

Around the world and back: The enduring influence of Black gospel music

Black Gospel Music Preservation Program: Securing the legacy of Black Gospel music