How many times have you heard Black religious leaders preach, teach and advocate about reparation for racial injustice?

I have pondered that question a lot, especially since the murder of George Floyd. I have wondered why Black religious leaders are not talking about reparation to their congregations.

Wendell Griffen

Why do Black religious leaders engage in conversations with white religious people about racial “reconciliation” that does not include reparation for 250 years of forced labor without pay, another century of legalized apartheid, continuing homicidal and abusive conduct by government agents operating under the guise of “law enforcement,” and other aspects of the systemic racial injustice that pervades U.S. society?

How can Black religious leaders avoid talking among themselves about reparation?

How can Black denominations hold education conferences without conducting serious study, including Bible study, about reparation?

And what does it mean when Black religious leaders are not demanding reparation?

“What does it mean when Black religious leaders are not demanding reparation?”

What does it mean when Black religious leaders do not challenge Black elected officials, including Black legislators, to demand reparation from local, county, state and federal governments?

Before you dismiss my questions, I encourage you to read a book by Randall Robinson titled The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks that was published in 2000. Robinson’s book is an excellent analysis about the historical, moral, ethical and social factors that support reparation for racial injustice.

But I am especially impressed by Robinson’s unflinching message that reparation is what Black people are due, and that it is incumbent on Black people to say so. Consider this excerpt from the final chapter of his book:

The issue here is not whether we can, or will, win reparations. The issue is whether we will fight for reparations, because we have decided for ourselves that they are our due. …

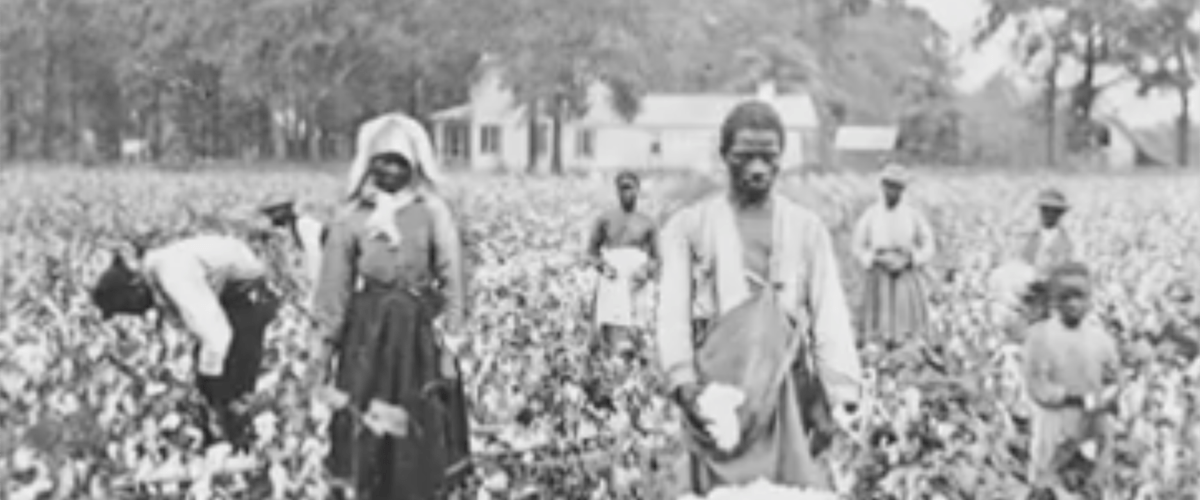

Let me try to drive the point home here: through keloids of suffering, through coarse veils of damaged self-belief, lost direction, misplaced compass, shit-faced resignation, racial transmutation, Black people worked long, hard, killing days, years, centuries — and they were never paid. The value of their labor went into others’ pockets — plantation owners, Northern entrepreneurs, state treasuries, the United States government. …There is a debt here.

Clearly, how Blacks respond to the challenge surrounding the simple demand for restitution will say a lot more about us and do a lot more for us than the demand itself would suggest. We will show ourselves to be responding as any normal people would to victimization were we to assert collectively in our demands for restitution that for 246 years and with the complicity of the United States government, hundreds of millions of Black people endured unimaginable cruelties — kidnapping, sale as livestock, deaths in the millions during terror-filled voyages, backbreaking toil, beatings, rapes, castrations, maimings, murders. We would begin a healing of our psyches were the most public case made that whole peoples lost religions, languages, customs, histories, cultures, children, mothers, fathers. … And they were never made whole. And never compensated. Not one red cent.

Religious leaders who are more offended because Robinson used the term “shit-faced resignation” — and that I quoted it — than they are about their own failure to demand reparation for racial injustice are part of the reason Black people are not demanding reparation.

Local, state and national Black politicians who do not demand reparation for racial injustice are part of the reason Black people are not demanding reparation.

Civil rights leaders who do not demand reparation for racial injustice are part of the reason Black people are not demanding reparation.

Black business leaders who do not demand reparation for racial injustice are part of the reason Black people are not demanding reparation.

I wonder why Black religious leaders, whose congregations are composed of Black people for the most part and who, therefore, have a measure of independence from white power that is at least different from — if not greater than — Black political, business and civil rights leaders, are not demanding reparation.

I wonder when Black congregations will insist that Black religious leaders take up that cause. Why are Black congregations not raising that issue with Black preachers and religious educators?

“Too much of Black religious thought is unwittingly influenced by white evangelical notions of theology infected by white supremacy.”

One possible explanation is that too much of Black religious thought is unwittingly influenced by white evangelical notions of theology infected by white supremacy. More Black religious thought is shaped by the mindset and methods of people such as Billy Graham, John MacArthur, Joyce Meyer, Joel Osteen and Jerry Falwell than people such as Richard Allen, Howard Thurman, Henry Highland Garnet, Sojourner Truth, Martin Luther King Jr., James Cone, Katie Elizabeth Cannon and Jeremiah Wright Jr.

Hence, the ministry of Bishop T.D. Jakes more closely resembles that of Joel Osteen than that of Adam Clayton Powell Jr. or his successor at Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, Samuel DeWitt Proctor.

Hence, leaders of Black churches have nostalgic views about Martin Luther King Jr. but shun the social justice thinking and activism done by King and his colleagues in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Hence, more Black church leaders spend more time planning and preaching in “revivals” than planning and collaborating about revolutionary strategies and activism against white supremacy and racism, capitalism, patriarchy and sexism, imperialism, militarism and the other “isms” that contribute to injustice.

Hence, Black church leaders, like their white counterparts, seem to be more interested in “saving” people for the afterlife than in following the example of Jesus who spent his ministry teaching people how to be agents of love and justice and healing them from conditions brought about by social and economic inequities bottomed in greed.

In other words, Black religious leaders seldom teach and demand reparation for Black people because too many of us take our cues from white religious leaders. Otherwise, we would be quoting leading Black liberation theologians rather than white evangelical thinkers. We would be unapologetically skeptical and unflinchingly critical of much of what passes for “evangelical” Christianity. We would spend more time teaching and preaching about and urging people to join God’s quest for love and justice than the afterlife.

We can retain reverence for the afterlife without disregarding centuries of systemic robbery and violence against Black, indigenous and other people of color. Doing so will require that Black religious leaders become “decolonized,” to borrow from the thinking of Latinx theologian Miguel De La Torre, author of Decolonizing Christianity: Becoming Badass Followers of Jesus.

As James Cone (who was reared in Bearden, Ark., educated at Philander Smith College, and nurtured by faithful parents and other Black elders) observed, what is needed is for Black preachers to unlearn the “borrowed theology” of “evangelical Christianity.” Instead, we need to learn, embrace, preach, teach and practice the radical religion of the swarthy-skinned Palestinian prophet named Jesus, whose ministry focused on love and justice.

I hope this column prods us to move in that direction.

Wendell Griffen is an Arkansas circuit judge and pastor of New Millennium Church in Little Rock, Ark.

Related articles:

Ideas for churches studying the need for reparations | Analysis by Andrew Gardner

5 reasons why reparations talk makes white people crazy | Opinion by Alan Bean

Beware the Anti-Anti-Racist Evangelical Complex | Opinion by David Bumgardner

What to do if you unearth a history of slavery in your church, college or institution?