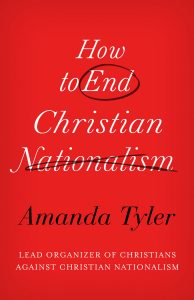

Abolishing Christian nationalism requires a firm understanding of the political ideology, a willingness to renounce faith-based violence and the courage to advocate against the racist movement at home and in the public square, Amanda Tyler said during a webinar about her new book, How to End Christian Nationalism.

For Christians opposed to Christian nationalism, a process of spiritual self-searching may also be necessary to identify and discard any personal beliefs that faith, nation and whiteness are synonymous, Tyler said during the Oct. 9 “change-making conversation” webinar moderated by Mark Wingfield, executive director of Baptist News Global.

Tyler’s book is available for pre-order and is scheduled for publication Oct. 22.

Tyler’s book is available for pre-order and is scheduled for publication Oct. 22.

“This is really calling on Christians to remember the core of our faith tradition, which is a gospel of love and central to the commandments of Jesus, and to understand how Christian nationalism is at odds with that gospel of love and to get back in touch with the core of our faith commitments,” said Tyler, executive director of Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty and lead organizer of the Christians Against Christian Nationalism.

Worship of power

A huge danger posed by Christian nationalism is its worship of power and its goal of replacing pluralistic democracy with a theocracy dominated by white, and mostly male, Christians, she added.

Wingfield noted BNG has published numerous stories about conservative Christian leaders and churches demonstrating self-love over love of neighbor. For example, during the pandemic, BNG reported instances of congregations refusing to close because they elevated their love of worship over love of neighbor. “It seems to me a pervasive denial of the loving message of the Gospels that is fueling not just this, but so much of the discontent in American Christianity,” he said.

Most of those who embrace Christian nationalism rarely quote the Gospels or point to the life of Christ, Tyler responded. “They are often cherry-picking other quotes out of the Bible, and I think really misinterpreting or twisting them in order to justify their own power play, their own equal and unequal ways of being and their own use of violence.”

Being rooted in the Gospels can help Christians educate others about the difference between Christian nationalism and a Christ-centered Christianity, Tyler said, a point she emphasizes in the book.

“I thought it was just really important, both for Christians and for others who are getting a warped sense of Christianity through the lens of Christian nationalism, to explain what Christianity is all about and to encourage Christians to rediscover the heart of that gospel message so they can be better messengers of that love, both with their words, but more importantly with their deeds in our communities,” she said.

Eight steps

Tyler’s book is divided into eight chapters defined as steps, each being crucial in enabling Christians to oppose Christian nationalism. Digging deeper into the faith is the second step, while understanding the ideology and denouncing violence are the first and third. The remainder are committing to the separation of church and state, confronting the ideology at home and in local churches, organizing against the belief system, safeguarding religious freedom in public schools and taking the struggle into the public square.

“We will not end Christian nationalism if Christians do not actively work to dismantle it.”

“We will not end Christian nationalism if Christians do not actively work to dismantle it: to rid it from ourselves, our congregations, and our larger communities,” Tyler explains in the foreword. “For Christians who are committed to this cause, basing our activism in our faith provides the motivation and the sustenance to persevere in this hard work.”

But reading this or any other book will not end Christian nationalism, she adds. “And make no mistake: this will not be an easy road. Christian nationalism is deeply entrenched in U.S. society. Because generations have let Christian nationalism fester, the ideology has grown deep roots, creating an underground system that makes it that much harder to extricate.”

Amanda Tyler

She also warns readers that discussing Christian nationalism requires a venture into race and racism.

“White Christians need to learn the history, question assumptions and be willing to shift our own narratives about what it means to be Christian and what it means to be American,” she writes. “We also need to raise our self-awareness — particularly our awareness about the power we hold because of our whiteness — to avoid the very real danger of perpetuating white Christian nationalism in our efforts to dismantle it.”

Those actions must begin with an understanding of Christian nationalism, which Tyler defines as “a political ideology and cultural framework that seeks to fuse American and Christian identities. It suggests that ‘real’ Americans are Christians and that ‘true’ Christians hold a particular set of political beliefs. It seeks to create a society in which only this narrow subset of Americans is privileged by law and in societal practice.”

This isn’t new

While many Americans first became aware of Christian nationalism as the driving force of the January 6 insurrection, it actually has been present throughout U.S. history and is currently on the rise, she writes. “Christian nationalism is pernicious and insidious, and its influence in the United States is rising at an alarming rate. It is up to each of us to confront and call it out as the destructive ideology that it is and for the damage that it is causing our country — and the world.”

Calling out that ideology also means highlighting its promotion of, and reliance upon, violence. Tyler provides numerous recent examples of violence ranging from the January 6 uprising to the “Unite the Right” rampage in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017 to the Tree of Life synagogue massacre in 2018. Rhetorical and political violence also are to be condemned, she advises.

“This exclusionary and divisive system is perpetuated by the myth that the United States was founded as, is now, and always should be a Christian nation.”

“If we ignore the connections between these events — the root structure of hatred and bigotry that links the shooters and the networks and the theories — we fail to see the reality that is confronting us,” she writes. “Rejecting violence and pursuing peace is an esteemed part of the Christian tradition, with analogs in other major religions as well. We can find the source and sustenance for our work against violence in our faith.”

Standing up for the separation of church and state is critical because the concept is ignored or disparaged within Christian nationalism while religious freedom is distorted to infer exclusive protection of white conservative religious beliefs, she says. “This exclusionary and divisive system is perpetuated by the myth that the United States was founded as, is now, and always should be a Christian nation.”

That concept has bubbled up in American life in numerous, often unnoticed ways, including through American flags in sanctuaries, slogans such as “in God we trust” and in the general conflation of patriotism and nationalism. But just as religious leaders are beginning to speak up against the ideology, laypeople can name and condemn it within their immediate circles of influence and by advocating for religious freedom for all, she believes.

And conversations with family, friends and fellow church members must avoid labeling others as Christian nationalists, she adds. “One of the most important starting places for conversation is a commitment to viewing Christian nationalism as an ideology, not an identity. … It exists in the culture, and we all face opportunities to either embrace it or reject it.”

American exceptionalism

A webinar participant asked Tyler if there is a connection between the doctrine of American exceptionalism, the idea that the U.S. is morally and religiously unique, and the racial violence and injustice inherent in Christian nationalism.

“Christian nationalism is not just an attack on equality, but it’s also, from a theological point of view, a perversion of the gospel.”

The ideologies overlap in their “use of some kind of spiritual or biblical or scriptural basis for taking land that European Christians, and by extension white Americans, have some kind of special role that is exceptional and better than others,” she replied. “And in this way, Christian nationalism is not just an attack on equality, but it’s also, from a theological point of view, a perversion of the gospel.”

That answer, Wingfield responded, reminded him of author Tim Alberta’s September lecture at Baylor University, where he described Christian nationalism as an “alliance between bad history and bad theology.”

Tyler agreed. “And this goes with American exceptionalism as well, the history of America as a ‘Christian nation’ is a cherry-picked history. It’s one that uses selective founders’ biographies, combined with taken-out-of-context quotes to create a story that actually doesn’t match an honest reading of history or the constitutional text itself. And that’s the bad history that comes into play.”

Reason for hope

Wingfield observed that Tyler seemed to be much more hopeful on the subject of Christian nationalism than a lot of other experts on the topic: “You seem a little more optimistic than the Debbie Downers like me.”

She gave several reasons for hope, including a vigorous response to the Christians Against Christian Nationalism campaign and seeing others organizing to oppose the ideology: “They are horrified to be associated with Christian nationalism as Christians and horrified to see their faith used in that way and really motivated to do something about it.”

In addition, polling suggests general acceptance of Christian nationalism is declining. “I want to encourage people that there are more of us who are concerned and pushing back against Christian nationalism,” she said. “We need to normalize speaking out against Christian nationalism and also encourage each other to get more directly involved in our pluralistic democracy.”

Why, then, does it seem the voices of Christian nationalism seem to be the loudest? Wingfield asked.

It’s because the agenda of Christian nationalism is being financed by some wealthy Americans who prefer totalitarianism over democracy, she said. For example, “two billionaires are funding a push for authoritarian theocracy in Texas, and Christian nationalism is motivating them. Because of their power, influence and money, their ideas are being pushed on everyone else in Texas — ideas that are a minority position, even in a place like Texas. Some people listening in from around the country might not know that. They might just assume because of the policies that people in Texas agree with them, and that’s just not the case.”

Watch the entire webinar here.

Related articles:

Defining who’s a Christian nationalist isn’t as easy as it looks, Pew researcher says

Kentucky panelists discuss the threat of Christian nationalism

How to tell if it’s ‘Christian nationalism’ or not