After racist incidents brought calls for greater inclusiveness at a large Dallas-area school district, Christians, pastors and churches citing “faith, freedom and family” helped rally a conservative backlash against “wokeness.”

“We are not asleep anymore,” said one conservative during one of many heated school board meetings. Another called the conflict “a classical battle between good and evil, light and darkness, truth and deceit, perception and reality.”

“We must rise up and work hard to protect our traditional way of life, which is currently under attack by extremists,” said another of the conservatives.

Mike Hixenbaugh

A powerful new parent group at Carroll Independent School District in Southlake, Texas, successfully halted efforts at inclusion, replaced the school board and worked to “put God back into our schools” by requiring school classrooms to post “In God We Trust” posters provided by Patriot Mobile, a cell phone company that donates a portion of users’ monthly bills to help Christians take over American society through the Seven Mountains Mandate.

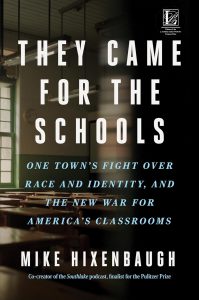

Covering it all was award-winning NBC reporter Mike Hixenbaugh. And he tells the full story in his new book, They Came for the Schools: One Town’s Fight Over Race and Identity, and the New War for America’s Classrooms.

He says Texas anti-woke activists were part of a nationwide “two-front battle in the war over education.”

“While fighting to win public funding for private Christian schooling, they simultaneously pushed to impose conservative Christian values inside public school classrooms,” he writes.

He paints a picture of Southlake — located northeast of Fort Worth — as a community where “to be truly conservative … seemed to mean never associating or compromising with people of different political beliefs.”

In an interview, Hixenbaugh said he was raised Southern Baptist at the small First Baptist of Garrettsville, Ohio, and later attended “large nondenominational evangelical churches like the ones I traveled to when I was writing the book.”

He says his faith shaped his worldview and his professional calling. “I got into journalism, in some ways, to live out my faith by shining a spotlight on injustice and elevate stories of people doing good things.”

He says his faith shaped his worldview and his professional calling. “I got into journalism, in some ways, to live out my faith by shining a spotlight on injustice and elevate stories of people doing good things.”

He found some of both at Carroll ISD — employing the common Texas shorthand for all school districts. The district takes it name from a man affiliated with the violent racist group the Ku Klux Klan, but educational standards in Texas prohibit the study of the Ku Klux Klan, school segregation or anything that leads students to feel “discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress” because of their race.

Southlake is an affluent, mostly white enclave where “politics permeates Christian spaces” religion is a powerful driver of hard right conservatism, and subtle or not-so-subtle racism permeates life for those who aren’t white, he explains.

Local conservatives used their connections to celebrities to make their local battle against inclusion a national news story on conservative media. Among the local celebrities:

- Robert Morris of Gateway Church, one of the largest congregations in the country

- Dana Loesch, a radio show host who formerly worked with the National Rifle Association, Breitbart News and Glenn Beck’s TheBlaze TV

- Christian nationalist “historian” David Barton

- “Trump prophet” Lance Wallnau

- Political operative Allen West, who railed against inclusion from the pulpit of First Baptist Grapevine, a Southern Baptist church where local activists met, saying inclusion was a lie imported by newcomers “who did not understand the lesson that God told Lot when he was destroying Sodom and Gomorrah.”

Soon, Tucker Carlson was telling his Fox News audience what was happening in Southlake was an affront to “legacy Americans” who held “traditional American values.” Another conservative report was headlined: “Parents revolt after Texas’s number one school district tries to institutionalize racism.”

“You play the tape showing what really happened, but it’s the perception that matters more.”

Locals raised hundreds of thousands of dollars and hired national political consultants to create a campaign characterized by bad faith and false claims, including the claim that the school district planned to hire “diversity police” to round up those who weren’t sufficiently inclusive.

Part of the campaign was a mailer featuring an image of a white child cowering in a school hallway under the words, “Restore Safety.”

Hixenbaugh said his reporting confronted him with the political power of false claims, some of them promoted by Christian activists who knew they were false. These false attacks became part of the model Southlake exported to other communities.

“I knew this on an intellectual level,” he says, “but it was stunning to watch false information being spread around. And it really doesn’t matter what you do to correct that. You play the tape showing what really happened, but it’s the perception that matters more.”

Some conservatives started calling Hixenbaugh “Fiction-baugh.” That didn’t bother him, but it did shake him up when someone threatened to file a police report claiming he was sexually “grooming” one of the teenagers he interviewed.

He said the experience of being called a child sexual predator showed him how it feels to be on the receiving end of the kinds of abuse some teachers and librarians face daily.

Related articles:

The dangers of minority rule | Opinion by Mark Wingfield