In 1916, a 26-year-old Darley Hiden Ramsey submitted a motto for the newly commissioned town seal of Asheville, N.C. His choice, levavi oculos meos in montes, “I lift my eyes to the hills” was taken from Psalm 121.

Scholars consider this work as part of the Jewish Songs of Ascent and believe it was sung by pilgrims as they ascended the holy city of Jerusalem.

This past week, I have taken the words of the Psalmist to heart. Like Ramsey, my eyes have been set on what I know to be sacred hills, those ranges of pushed-up earth that acted as backdrop to some of the most significant moments of my life. My memory rests in the shadows of their prodigious peaks, those ancient of days, where my spouse, Lauren, and I spent so much time.

Justin Cox

In Asheville, we snaked through alleyways while watching the moon beat down the mountains around us. Our ears perked like coyotes at the whisper of local legends, leaving us to lean on each other when the folklore and wind grew too cold. One Valentine’s weekend it snowed, so we ice skated like fools in our thin canvas Tom shoes into destinations where we warmed ourselves with drinks and laughter. On another occasion, we popped in a tiny shop and bought a pacifier on a whim for a baby whose name we didn’t know yet. It sat in a dresser drawer for years until she finally came along. We honeymooned all over these streets.

Until recently, those scenes rested in my recollections without blemish. However, something has challenged how I now remember this place. The scene has changed in the theater of my mind.

My great aunts Emmie and Minnie were children of Appalachia. Their expressions and dialect echoed a way of life I saw lived and sometimes felt part of. I experienced this the most during summer months when I practically never left their sides. On blistering afternoons, the sky would grow dark, and the wind ceased its whisperings. Those two old women would stand on their front porch, poised as two prophetesses, and declare to any within earshot, “It’s fixin’ to come up a cloud.”

I thought of them as I watched in awe and horror as Hurricane Helene drowned everything in its path. Like Hazel in 1957 and Hugo in 1989, it was a hurricane of biblical portions. The sky filled with storm-bearing clouds, opened and forgot to close. Leaving everything submerged under swill.

Most of it still is.

Homes, businesses, farms. Loved ones. Taken away.

And somewhere, underneath all the layers of mud, my pristine memories are buried, too.

Too bitter to add another drop to the flood covering my holy ground, I’ve kept my tears to myself. Those impacted, many whom I count as my people, don’t need any more water.

In the aftermath, I have seen signs of resilience and hope — standard virtues found in Appalachia. Outside of local and national news reports, I’ve read texts messages and seen social media updates of friends who call places like Black Mountain, Burnsville, Swannanoa, Boone, Candler and Bakersville home.

In the middle of picking up pieces of what’s left, residents are checking in on one another. Lists of resources are being made available. Those with generators are sharing power. Signs hammered into fence posts detail road conditions and whiteboards lean up against piles of debris at the top of washed-out driveways with handwritten instructions on where a single bar of cell service can be found. Schools and churches still standing have become food shelf stations.

Tragedy often brings out the best in humanity. In such times, strangers become neighbors and differences are put aside. The lions lay down with the lambs and folks come together. Everyone seems to get that to make it through this mess, we need some sense of unity.

Well, not everyone.

“The last thing anyone in Western North Carolina needs is a pandering politician looking to exploit them in hopes of swinging the state toward their favor.”

In a completely expected series of events, Donald Trump took to social media to unload his displeasure with how relief efforts were unfolding for those impacted by the storm. The former president wasted no time inserting himself into a situation where the last thing anyone in Western North Carolina needs is a pandering politician looking to exploit them in hopes of swinging the state toward their favor.

Luckly this wasn’t the vice presidential debate, and news sources like the Charlotte Observer and Raleigh News & Observer already have responded to many of the outlandish claims. This, however, has not stopped Trump and his supporters from continuing to spread disinformation.

This is a pattern I’ve seen before, and I’m done going in circles in trying to point out why this behavior is problematic.

No, I will not waste one more breath trying to convince MAGA followers why North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper isn’t withholding aid from red-voting counties or why the federal government isn’t building and testing hurricane machines on its people. I’m done trying to present scientific data on climate change and why it’s leading to higher intensity storms. You will not hear a peep from me about FEMA funds being available, and that they haven’t been sucked dry by undocumented immigrants. The days of my getting worked up and feeling obligated to point out facts is over.

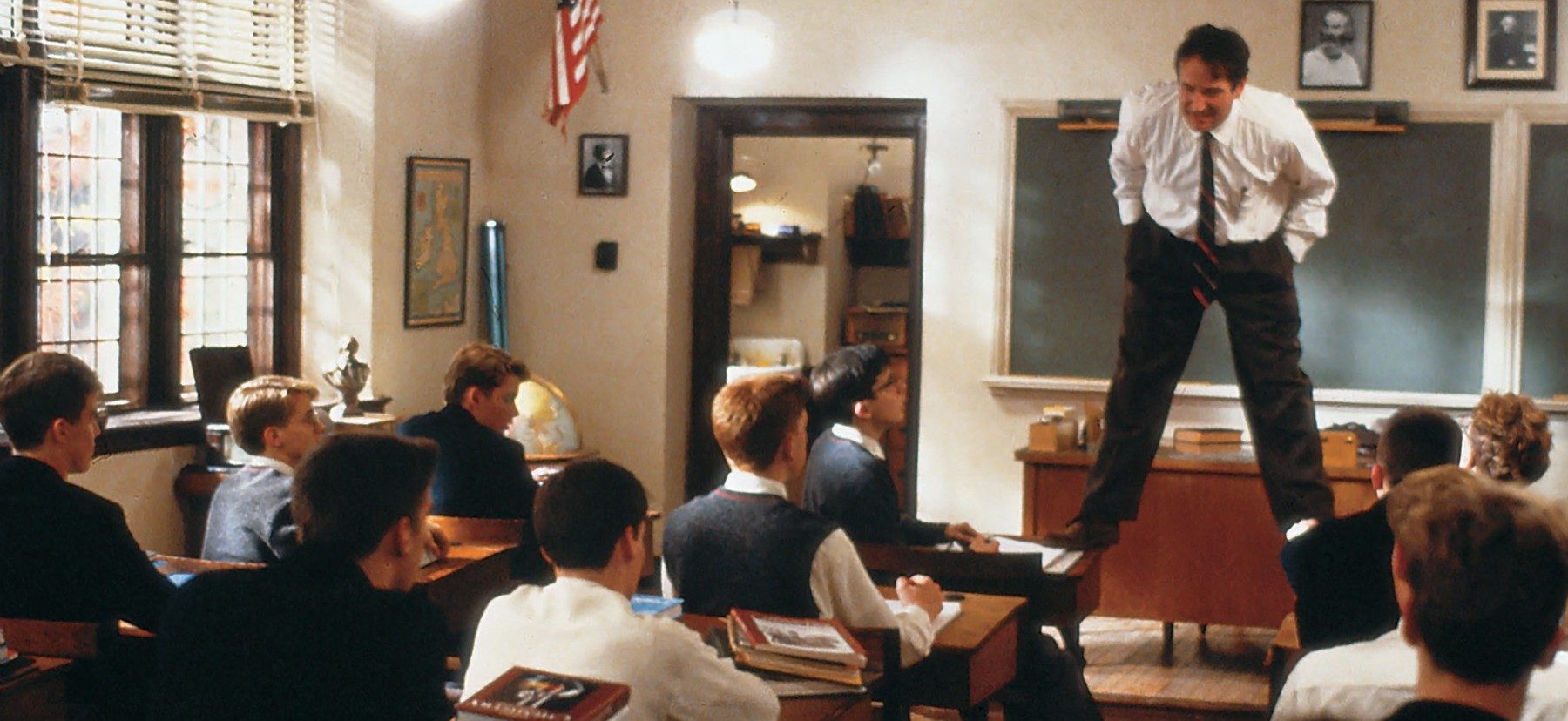

Robin Williams in “Dead Poets Society.”

Instead, I’m taking another approach.

In the film Dead Poet Society, actor Robin Williams portrays an English prep schoolteacher who exposes his students to poetry. Their first encounter is reading an introduction from their textbook describing what poetry is supposed to be and what constitutes a good poem. Williams’ character writes on the chalkboard as a student reads the description. When the student finishes, Willams turns around and states to young and impressionable ears, “Excrement.”

He doesn’t debate the author of the textbook. He doesn’t cite other scholarship as to why this point of view is wrong. He doesn’t waste the students’ time trying to offer a perspective as to why this is or isn’t a valid view.

He just says one word — excrement.

Feces, manure, crap, droppings, caca, “number two,” dung, stool, poop, doo-doo, waste, scat.

When accusations come with the intent to sow seeds of disharmony, I’m going to start doing the same thing. I’m going to call it out for what it is.

Bullshit.

And people struggling to have their more basic of needs met right now don’t need any of it.

For the love of God, can we please do better right now?

Justin Cox received his theological education from Campbell University and Wake Forest University School of Divinity. He is an ordained minister affiliated with the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and enrolled in the Doctor of Ministry program at McAfee School of Theology. When not spending time with his spouse and daughters, he can be found writing and baking late into the night. He currently resides in New England with his family. His thoughts and reflections are his own.

Related articles:

Megan Basham is lying again | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Talking about politics | Opinion by Mary Elizabeth Hanchey

Disasters bring out the best and worst theology | Opinion by Paula Garrett