Conceptualizing the American religious landscape can be a challenging task these days. We may think about Roman Catholicism’s prevalence in parts of New England or Lutheranism’s prevalence in the Midwest. Mormonism certainly composes a significant portion of the population in Utah and other parts of the American West. Judaism similarly has large populations in New York City and South Florida.

When attempting to locate evangelical Christianity, popular opinion often thinks of the American South. Certainly, evangelicalism has significant strength in this part of the country — but positioning evangelical Christianity’s authority within the American South obscures the historical evolution of this religious movement. It cloaks the ways in which evangelical politics came to be synonymous with the politics of limited government deregulation that have come to characterize the Republican Party.

When attempting to locate evangelical Christianity, popular opinion often thinks of the American South. Certainly, evangelicalism has significant strength in this part of the country — but positioning evangelical Christianity’s authority within the American South obscures the historical evolution of this religious movement. It cloaks the ways in which evangelical politics came to be synonymous with the politics of limited government deregulation that have come to characterize the Republican Party.

While many Republicans decry the state of the party today, California provided the staging ground for creating the American evangelicalism that we now know, and California continues to be a prominent center of evangelicalism in American culture.

According to the Pew Research Center on Religion and Public Life’s Religious Landscape Study, 70.6% of the total population in the United States identifies as Christian, and roughly a quarter of the total population would characterize themselves as “Evangelical Protestant.”

Breaking down the geographic landscape of American evangelicalism, however, can be much more difficult. In the American South, colloquially referred to as the “Bible Belt,” 34% of the total population identifies as evangelical compared to just 22% of the total population in the American West. This statistical difference widens when comparing individual states. For instance, 1 in 5 adults in the state of California identifies as evangelical, while just over 1 in 2 adults in Tennessee use this label.

Statistics, however, can be misleading and skew our perception. California is the most populous state in America, which means 20 percent of the state’s population identifying as evangelical comes to just under 8 million people. California’s evangelical population is larger than the total population of 38 states.

Franklin Graham (Photo/Matt Johnson/Creative Commons)

Recognizing California’s large evangelical population and the potential to wield that identity for politic change, Franklin Graham held 10 large, campaign-style rallies in California leading up to the 2018 midterm elections. The caravan bus tour sought to energize evangelical voters in order to break California’s “Blue Wall.” The campaign also likely functioned to loosen the pocketbooks of evangelicals in the state who make up the second largest donor pool for Samaritan’s Purse, Franklin Graham’s international nonprofit known best for Operation Christmas Child. California evangelicals hold power in the larger evangelical community.

How evangelicalism came to have such strength in the Golden State is a story more than 100 years in the making. Historian of American Religion Darren Dochuk chronicles this development in his book From Bible Belt to Sun Belt: Plain-Folk Religion, Grassroots Politics, and the Rise of Evangelical Conservatism.

The United States witnessed significant change from the 1920s to the 1940s. After emerging from World War I into a period of growth during the Roaring Twenties, the country was flung into the Great Depression only to quickly be thrust back into global war with World War II. This roller coaster of a period witnessed the migration of many white Southerners to industrial cities. Families in the southern plains traveled West — as fictionalized in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath — in order to escape the Dust Bowl. By 1970, Duchuk writes, “11 million Southerners — 7.5 million whites, 3.5 million Blacks — lived outside their home states.”

The car of an “Okie” moving from Oklahoma to California in 1941 was captured in this government photograph,

Southern California was a beneficiary of this migration. Duchuk suggests that rather than see their migration as an “exodus” as many Black southerners did, white Southerners saw their migration as an “errand” in which they might spread God’s word. As these white Southern evangelicals sought to evangelize the West Coast, they turned their eyes toward politics.

Following World War II, evangelicals began to realize that the liberal policies of the New Deal were to become a permanent fixture of the party’s platform. Roosevelt’s policies were largely welcomed, Dochuk notes, as a “temporary correction to the excesses and failings of capitalism.” A more permanent implementation of New Deal policies, evangelicals feared, too nearly resembled the “godless communism” that post-war America had identified as its chief adversary.

Robert P. Shuler. Creative Commons

Robert “Fighting Bob” Shuler — not to be confused with Robert Schuller who later founded the Crystal Cathedral — led the charge for evangelicals to break ranks with the Democratic party. An American evangelist and radio broadcaster, Shuler had been a lifelong Democrat. He possessed a flair for being a combative and accusatory radio personality. After the Federal Radio Commission revoked his broadcasting license for “numerous abuses,” Shuler made a strong but ultimately unsuccessful run for the U.S. Senate on the Prohibition ticket. His popularity and political evolution, however, helped open the opportunity for a new alliance between evangelicalism and corporate business.

Throughout the 1950s, evangelical preachers and entrepreneurs created a powerful coalition that gave evangelicalism in California a growing political clout. Evangelicals in the state came to advocate for limited government and established new teachings on wealth that emphasized a “personal ethic of stewardship and proper money management.” No longer the poor evangelicals who migrated from the South, California evangelicals were flush with money.

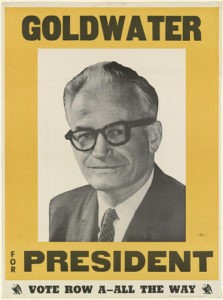

Barry Goldwater campaign poster, Smithsonian Museum.

Money meant a greater role in political campaigns, and in 1964 California evangelicals worked to nominate Barry Goldwater, a Senator from Arizona, as the Republican nominee for president of the United States. Goldwater’s defeat in the 1964 election laid the groundwork for then-California Sen. Richard Nixon’s successful campaign for the presidency in 1968. Nixon’s campaign understood that the support California evangelicals showed Goldwater provided an avenue for reaching out to white, Southern voters disaffected by the Civil Rights movement.

By 1971, during Nixon’s first term as president, Billy Graham declared before the California State Legislature, “I believe we can start a glow and a fire here on the West Coast that can sweep this nation.” It was not in the South, but the West where the tinder for an alliance between evangelicalism and business was set.

Evangelist Billy Graham and President Nixon wave to a crowd of 12,500 at ceremonies honoring Graham at Charlotte, N.C., on Friday, Oct. 16, 1971. (AP Photo)

Understanding the development of evangelicalism in the American West helps explain the rise of the Moral Majority and its support for yet another California Republican who ran for president in 1980 — Ronald Regan. Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson were not inventing a new way for evangelical Christians to engage with American politics out of thin air; rather they were building upon a tradition of evangelical engagement with American politics. This engagement continues to the present day.

As of July 1, the Pew Center reports that 82% of evangelicals plan to vote for Donald Trump in the upcoming presidential election. The Atlantic’s Peter Wehner characterizes this partnership as a “betrayal.” He contends that after nearly four years of the Trump presidency, all evangelicals have to show for their support is a Supreme Court justice who recently sided with the court’s liberal justices to protect LGBTQ employment rights and strike down an unconstitutional abortion law in Louisiana.

While gay rights and abortion rights effectively galvanize evangelical political engagement, suggesting that evangelicals have nothing to show for their support of Trump obscures the longer narrative that brought evangelicalism and corporate business together in common cause. As the case of California shows, limited government and deregulation have been part and parcel of evangelical politics since after World War II. It is no coincidence that Trump holds a slight edge over Joe Biden when pollsters ask voters whether candidates make good decisions about economic policies. This is an evangelical issue.

As the uncertainty of the economy continues in the wake of the current COVID-19 pandemic, it remains to be seen how evangelical support for Donald Trump will evolve. Given the close relationship that evangelicals have forged with Christian entrepreneurs and corporations, however, as long as the economy remains relatively stable, evangelicals’ support for Trump will likely continue, social issues be damned.