Diana Garland’s 1995 firing as social work dean at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary had less to do with her public conflicts with the Kentucky seminary’s leadership than with the surge of fundamentalism in the SBC and American evangelicalism, according to author and historian Melody Maxwell.

Maxwell, associate professor of church history at Acadia Divinity College in Nova Scotia, Canada, spoke during the latest episode of the “Making Baptist History Public History” webinar series presented by the Baptist History and Heritage Society.

“Garland’s dismissal was not simply the product of her public conflicts with [SBTS President Al] Mohler. Instead, it resulted more broadly from the tensions built up as conservative control overcame moderate tolerance,” Maxwell said.

She is co-author of Doing the Word: Southern Baptists’ Carver School of Church Social Work and Its Predecessors, 1907–1997.

Diana Garland

After being fired at Southern Seminary, Garland went on to became the founding dean of Baylor University’s School of Social Work for a decade before her premature death in 2015. That school now is named in her memory. Southern Seminary closed the Carver School in 1997.

Both Garland and the Carver School of Church Social Work she headed at Southern Seminary were victims of conservative distrust of social work ministry as a whole, Maxwell said. “Social ministry efforts, which Southern Baptists had undertaken to some degree throughout their history, were questioned as denominational leaders feared that liberal influences had tainted them. But this controversy clearly resulted from, and was paradigmatic of, the broader conflict between moderates and conservatives in the SBC.”

Maxwell was joined in the session by her Doing the Word co-author Laine Scales. Like their 2019 book, they traced the history of the Southern Baptist social work movement and the educational institution that shaped and nurtured it.

Scales said the Carver School was launched as the Woman’s Missionary Union Training School for Christian Workers in 1907 before evolving into the Carver School of Missions and Social Work in 1952. The school merged with Southern Seminary in 1963 and it was renamed the Carver School of Church Social Work in 1984.

Scales also outlined the historic and persistent tensions that ultimately led to the Carver School’s closure by denominational forces that viewed social work and women in leadership with suspicion.

That strain was present from the outset as training school women were allowed to attend limited classes at Southern Seminary, but not for credit. Nor were women permitted to use common dining or social spaces, as they lived and took most courses on their own nearby campus.

“The seminary needed to ensure Southern Baptists that the women were not preparing to preach.”

“The seminary needed to ensure Southern Baptists that the women were not preparing to preach,” Scales said.

While the curriculum during the first 40 years led to bachelor’s or master’s degrees in missionary training, the coursework also included classes to prepare women for married life, Scales said.

“They practiced music and elocution skills in the daily women’s chapel services. One student recalled years later that students were always reminded to step to the side of the pulpit when they spoke publicly, for no lady would stand behind the sacred desk.”

Goodwill Center, operated by the WMU Training School, ca. 1915.

(Photo from Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archive)

The 1950s saw new developments, including a curriculum focused as much on social work as missions, and enrollment opened to men and people of color. The school welcomed its first two Black students in 1955.

Despite those moves, enrollment declined and revenues with it, in part because women were being allowed to enroll at the seminary. When the SBC refused to increase funding to match the shortfalls, all Carver School assets were transferred to the SBC and the program was rolled into Southern Seminary in 1963, Scales explained.

The institution was resurrected as the free-standing Carver School of Church Social Work at the seminary in 1984, gaining full accreditation from the Council for Social Work Education, Maxwell said. The school’s return was inspired by Carver alumna Anne Davis, who had joined the seminary’s religious education faculty in 1970. She was a proponent of church-based social work designed to collaborate with other church ministries.

“Davis would frequently say the church, to be the church, must be involved in social ministry,” Maxwell explained. “She implicitly challenged the position some Southern Baptists and other evangelicals had about social ministry, which they considered a distraction from the heart of the gospel.”

Garland, who was hired by Davis and eventually succeeded her as dean of the Carver School, took the concept further with the belief that “Christian social workers could help the church understand the needs of persons, define those needs as a ministry challenge, and find ways to equip church members for effective service,” Maxwell said.

But these practices, coupled with Carver School teachings about underlying social causes of suffering and healing, drew the attention of conservatives who were in the process of taking control of the SBC and its institutions.

“These types of systemic understanding of social issues were actually suspect among many Southern Baptist conservatives who saw individual sin as the root of people’s problems.”

“These types of systemic understanding of social issues were actually suspect among many Southern Baptist conservatives who saw individual sin as the root of people’s problems. And these divergent perspectives would soon openly conflict within Southern Baptist life,” she said.

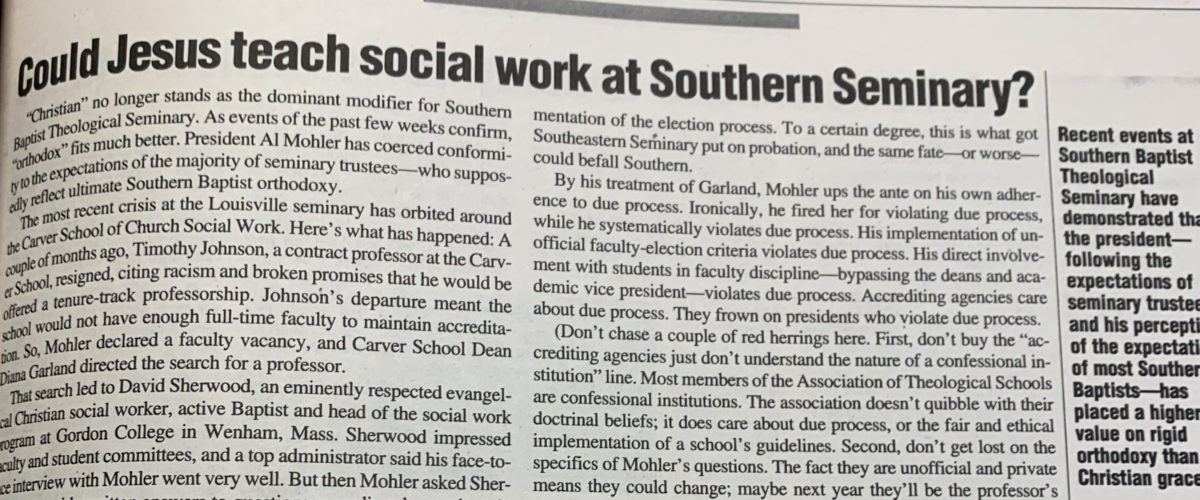

The open struggle began to build shortly after Al Mohler became president of Southern Seminary in 1993, Maxwell said. He and Garland clashed when he refused to hire a professor for the social work school because of the candidate’s openness toward women in ministry.

“He then shifted his concerns to the nature of church social work. He asserted that the culture of social work and (Christian theology) were not absolutely congruent,” Maxwell said. “He told Garland he was deeply suspicious of any therapeutic modalities.”

Mohler also objected to the code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers, which prohibited discrimination based on age, sex, gender, race and sexual orientation, she said. “In Mohler’s view, this code demonstrated a moral neutrality that left no room for confessional Christianity.”

As a result, the Carver School, its faculty and students found themselves at odds with seminary leadership and the conservative movement they represented within the SBC, Maxwell said.

“Christian social workers, like those at the Carver School, believed their faith provided a strong impetus for social work. A commitment to non-discrimination, as Garland and the Carver faculty understood it, meant providing equal services to all clients, as Christ would have done. And they thought Christian social workers could then counsel their clients in a way consistent with their Christian beliefs. But the trustee committee and Mohler believed faculty members should unequivocally voice their conservative positions and publicly separate themselves from social work’s accrediting organization, no matter the consequences.”

While Mohler and the SBC won those battles, the spirit of the Baptist social work movement continues. Campbellsville University is now home to the Carver School of Social Work, while Samford University in Birmingham, Ala., and Baylor University in Waco, Texas, have faith-related social work programs, Scales noted.

“These are places where the seeds of what (the Carver School) began have continued to bear fruit.”

Related articles:

Diana Garland, social work educator and bridge builder, dies

Baylor renames School of Social Work for Dean Diana Garland

Social work leader Diana Garland’s legacy steers her children toward justice and mercy

From Carver School to Baylor: A legacy of ‘doing the word’ | Analysis by Laine Scales and Melody Maxwell