Greg Long wants to save Navajo language and culture — one Hebrew word at a time.

As a child, Long heard all about Navajo folklore from his paternal grandmother. That’s how he learned to say he’s “of the Deer Water People, born for the Yucca Fruit People,” the traditional Navajo introduction by way of his mother’s and father’s clans. It’s why he pinpoints geography by proximity to sacred mountains. It’s why his heart breaks when he meets young Navajos who can’t speak their language and who know nothing of their culture.

And it’s why he’s creating the first Bible translated into Navajo directly from the original Hebrew and Greek languages.

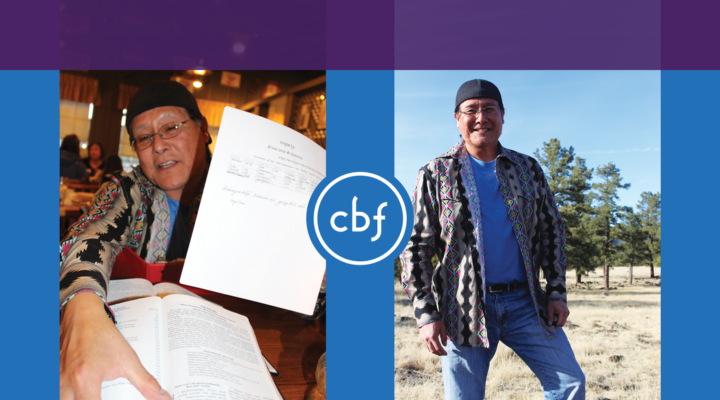

Greg Long, a member of the CBF West coordinating council, is heading up a program to create the first Navajo Bible translated from the original Hebrew and Greek languages. To start, he’s using worksheets from the Hebrew version of Genesis to translate scripture verses into Navajo.

Long grew up on the plateaus of north-central Arizona. Then he trekked to Sul Ross State University in West Texas, preparing to be a veterinarian. But along the way, he promised God he would become a minister. So, instead of veterinary school, he studied at Baylor University’s Truett Theological Seminary, earning a Master of Divinity degree with an emphasis on biblical languages.

While studying at Truett, Long founded Buffalo River Indian Baptist Church near the Baylor campus in Waco, Texas. After graduation, he moved home to Arizona, where he served as pastor of First Indian Baptist Church in Winslow and Grandfalls Bible Church in Grandfalls, before starting Selah Congregation in Flagstaff.

In 2015, Long and his wife, Sheila, transformed Selah Congregation into Selah Ministries. Now, they emphasize translating the Bible into Navajo and promoting Navajo language in worship.

By Long’s reckoning, the arc of his ministry makes divine sense: The best way to save Navajos’ souls is by saving their language and culture, too.

“Navajo as a language is increasingly in danger of becoming extinct,” he explained. The number of Navajos who speak their language has declined from 70 percent to 50 percent in the past 20 years. Alarmed leaders have introduced Navajo language courses at all levels of education.

“Still, the trend is toward obliteration,” Long lamented.

“In public spaces, I hear Hispanic and Asian babies and children speaking their own languages. But I hear Navajos—even the babies—speaking only English.”

Navajo teens reflect what happens when a people lose their culture, he added. He sees younger Navajos mimicking urban culture foreign to Navajo values—dressed in black, running in gangs, abusing drugs.

“They’re looking for identity, but their parents and grandparents can’t teach them their language; so they drift,” he said. “That’s why they talk and dress like youth from other cultures.” And it’s why they flee the traditional bonds of their families, he added.

“The Navajo language is holy and special,” Long insisted. “If we lose it, that will be a great tragedy.”

But a new Navajo Bible reflecting ecumenical Navajo input for Christian worship could “help curtail that trend in non-fluency,” he said. “This project could act as a sieve to lift out those Navajo cultural traits which bear resemblance to biblical precedence.”

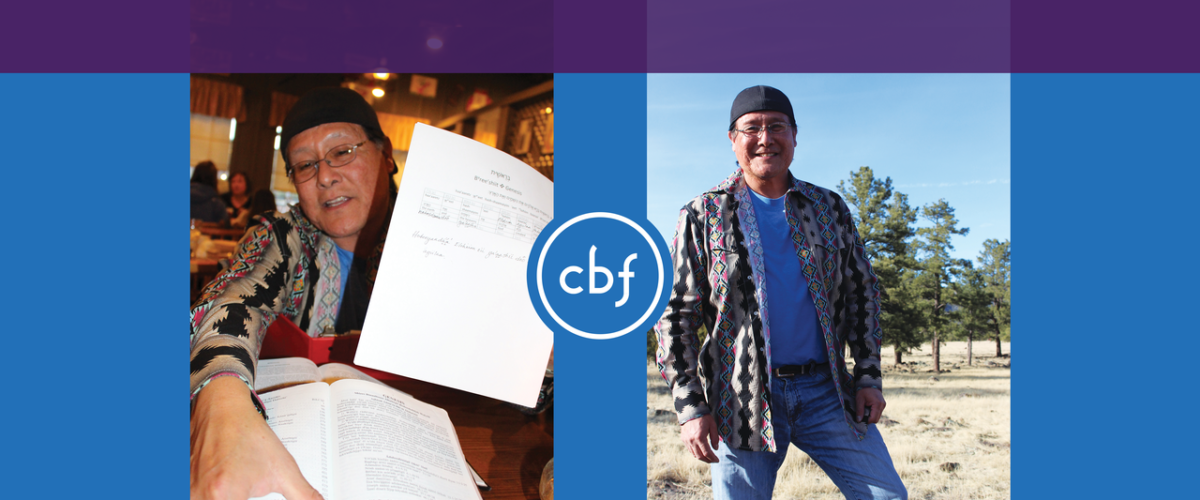

Sheila and Greg Long are pillars of CBF ministry among Navajos in northern Arizona. In addition to biblical literacy, their Navajo Bible translation promises to help young Navajos develop fluency in their historic language and also deepen their affinity for their culture.

It is “biblical precedence” that points to Long’s motivation. His studies of Navajo history and biblical Hebrew revealed striking similarities between Navajo and Jewish cultures—such as lunar-based calendars, kosher diets and even right-to-left writing. Jewish rabbis and Navajo medicine people commit long passages to memory and chant them in worship.

“Our people are ceremonial people, and the Jewish people are, too,” he explained. “But when you go to Navajo churches today, there’s no sense of ceremony.” The solution is for Navajos to learn from Jews, Long noted, adding, “In this new Navajo Bible translation, we’re allowing the Jewish people to teach us.”

He’s starting by translating the Bible into Navajo, beginning with Genesis, the first book in the Hebrew Bible. “We’re using contemporary, everyday Navajo language,” he reported. A word-for-word translation from the original languages, the new Navajo version will contrast distinctly from the current Navajo Bible, which was transcribed from the King James Version of the English Bible in Braille format, resulting in a Bible translation filled with “a lot of archaic Navajo.”

Long’s Navajo Bible Translation Project breaks the stereotype of a monkish interpreter, poring over ancient manuscripts, laboriously producing a new Bible a line at a time. It’s a community endeavor. He plans to teach Hebrew, and then Greek, to members of Western Navajo churches, who will work in teams to translate sections of Scripture. He’s piloting the project at East Valley Baptist Church, a Southern Baptist congregation in Flagstaff. Navajo members of the mostly Anglo church are learning Hebrew as they go, combining that skill with Navajo fluency to produce a wholly new Bible. Ultimately, their translation will present a Bible with left-hand pages featuring a Navajo translation utilizing English script. The right side will present a Navajo translation utilizing Hebrew script written right to left. Similar to the Hebrew Bible, the new Navajo Bible will include cantillation points that provide cues for chanting the passages.

“We don’t chant in our Navajo Christian worship services, but in our traditional ceremonies, we do,” he explained. “If the Gospel had been presented to the Navajos—and even the Apaches—in a biblical Jewish way, they would have latched onto it.”

In his dreams, Long envisions both translation and transformation. The project will produce a Navajo Bible formatted to Jewish liturgy. It will change the Navajos who implement it in their worship routine. Navajos will immerse themselves in their language, and they will renew their culture as well as deepen their faith, he hopes.

“This could change our Navajo culture for the better and, prayerfully, have a lasting impact on our people,” he predicted.

The next step is to create translation teams in other Western Navajo congregations, noted Long, a member of the CBF West coordinating council and a longtime advocate of CBF ministry in the region. “One of our requests,” he said, “is serious, heartfelt prayer for our teams.”

This article was first published in the Summer 2018 issue of fellowship! magazine, the quarterly publication of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. This special issue is devoted to Fellowship Southwest, CBF’s new regional network launched to strengthen ecumenical collaboration and to produce positive change in Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and Southern California. Visit www.fellowshipsouthwest.org to keep up with the work of Fellowship Southwest.

Subscribe to fellowship! magazine and CBF’s weekly e-newsletter fellowship! weekly at www.cbf.net/subscribe.