Charles Frazier Stanley, one of the best-known Southern Baptist preachers of the 20th century, died April 18 at age 90.

Raised in the Pentecostal tradition, Stanley was ordained to ministry by a Southern Baptist church as a young man, then attended a Southern Baptist seminary before launching into a career of service to SBC churches. The pinnacle of his influence in the denomination came with his election as SBC president in 1984 and again in 1985 — pivotal years in the so-called “conservative resurgence” in the nation’s largest non-Catholic denomination.

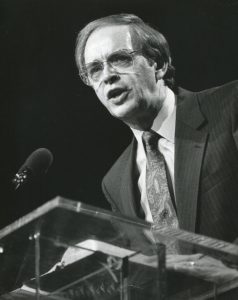

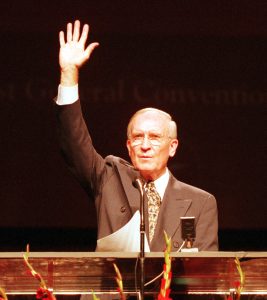

As SBC president in 1986 Charles Stanley won a standing ovation from messengers to the 1986 SBC annual meeting in Atlanta when he urged the denomination to “keep on moving in the direction we are going in to the glory of God.” (Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archives)

The primary reason Southern Baptist fundamentalist leaders recruited Stanley for that role is that he transcended the SBC like no preacher other than Billy Graham. The reach of his In Touch Ministries made him a household name in evangelical circles worldwide.

The radio and television broadcast originally called The Chapel Hour was renamed In Touch with Dr. Charles Stanley in 1978 when the Christian Broadcasting Network added the Atlanta preacher to its new satellite distribution network. According to information from In Touch, “the broadcast grew from 16,000 local viewers to a nationwide audience in just one week. Stanley was the country’s longest-serving pastor with a continuous weekly broadcast program.”

By 1982, two years before his election as SBC president, In Touch Ministries was incorporated and the In Touch radio broadcast entered syndication.

“During the 1980s, the In Touch program penetrated almost every major market in the United States, reaching more than 1 million households. At the time of his death, Stanley’s messages were heard in more than 127 languages around the world via radio, shortwave, the Messenger Lab project or TV broadcasts,” the ministry reported.

A celebrity president

The conservatives who were vying to take control of the SBC’s agencies and institutions — a battle begun in earnest in 1979 — followed a strategy of electing conservative presidents who would in turn appoint conservatives to a key committee that determined who would be nominated to serve as trustees of the SBC’s six seminaries and other agencies.

At the 1984 SBC annual meeting in Kansas City, Mo., Stanley garnered a 52% majority on a first ballot, outdistancing former Baptist Sunday School Board President Grady Cothen and John Sullivan, at the time pastor of Broadmoor Baptist Church in Shreveport, La.

Stanley became the fourth consecutive president elected with support of the “conservative” faction, following Adrian Rogers, Bailey Smith and Jimmy Draper. Observers expected a tighter race, because for the first time, “moderates” had mounted a concerted pre-convention campaign of their own.

The battle between these conservatives and moderates reached a fever pitch in 1985, when 45,000 messengers registered to vote at the annual meeting in Dallas. The crowd was so overwhelming, they snarled downtown Dallas traffic for hours as Southern Baptists attempted to get to the convention center.

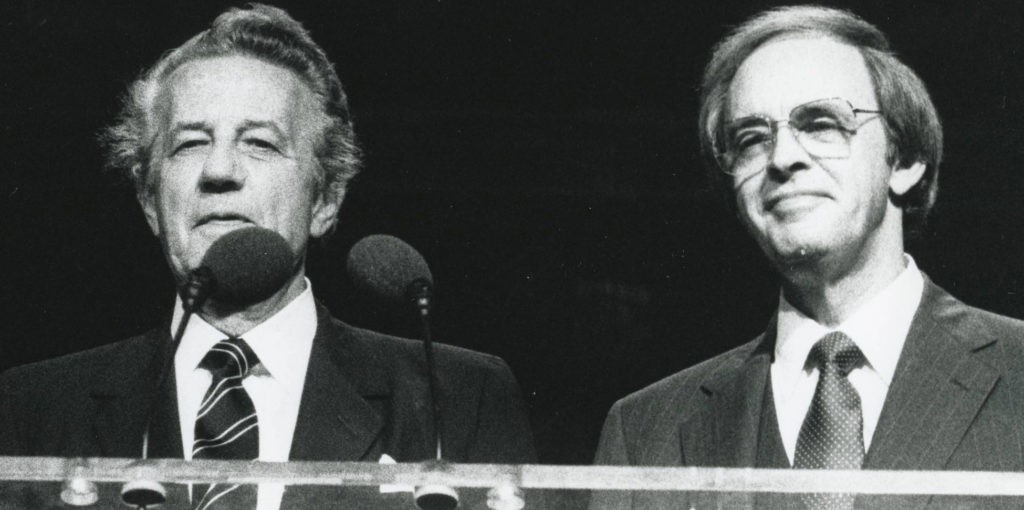

Charles Stanley (right) with Winfred Moore at the 1985 Southern Baptist Convention annual meeting in Dallas.

This time, Stanley faced another conservative opponent, but one who was not part of the takeover effort. Winfred Moore, longtime pastor of First Baptist Church of Amarillo, Texas, was a theologically conservative denominational loyalist called by some “the bishop of West Texas.”

The morning of the vote, Stanley’s allies publicized a telegram from Billy Graham supporting Stanley’s re-election. The Atlanta pastor won in a 55.3% to 44.7% ballot.

The die was cast, but most Southern Baptists didn’t yet understand that. The battle raged hotly for another five years and wasn’t fully settled until 15 years later, when the fully in charge conservative majority rewrote the SBC’s doctrinal statement to their liking.

By some accounts, Stanley was a reluctant candidate for the SBC presidency. Because of his international fame, the SBC conservative movement needed him far more than he needed them. And Stanley’s own church — which then was located within walking distance of the SBC Home Mission Board — was considered marginally involved in the denomination.

First Baptist Atlanta in its historic downtown location

At the time of his election, First Baptist Atlanta gave a nomimal contribution to the SBC’s Cooperative Program unified budget.

Nevertheless, by the time of his 2016 autobiography, Courageous Faith, Stanley saw himself as playing a divine role in the salvation of the SBC.

“All the liberal and moderate political forces of the Southern Baptist Convention were against me, which included seminary presidents and state convention newspapers,” he wrote. “I knew I was in the center of (God’s) will, so I never felt anxious or angry even when the conflicts were at their very worst.”

Early days at First Baptist

The suave TV preacher already knew something about controversy. His ascension to the pastorate at First Baptist Atlanta ranks as one of the greatest church fights of modern history.

First Baptist Atlanta already was an SBC megachurch before anyone used that term. It truly was the “first” Baptist church of the city in many ways, from its founding in 1848. The State Mission Board of the Georgia Baptist Convention officed there when formed in 1877. Every pastor at First Baptist was deeply involved in state and national denominational work. Georgia Baptists held large meetings at the church’s ornate facility.

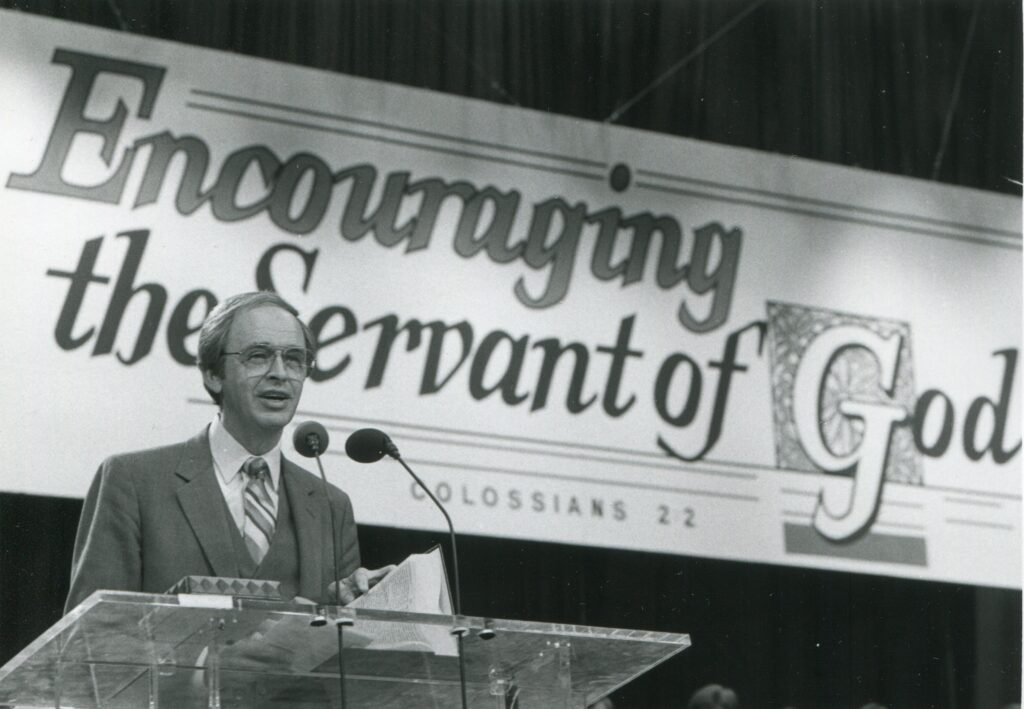

A young Charles Stanley preaching at First Baptist Atlanta.

Stanley’s predecessor at First Baptist was Roy McClain, who served from 1953 to 1970. Newsweek once named McClain one of the 10 greatest preachers in America. He preached on the Baptist Hour Sunday morning radio program, produced by the SBC Radio and Television Commission and aired nationwide.

Under McClain’s leadership, First Baptist became one of the largest churches in the nation.

An article published by Oral Roberts University picks up the story from there.

“In 1969, Stanley reluctantly accepted a call to move to First Baptist Church in Atlanta to serve as the associate pastor to Roy McClain, a very liberal pastor by Baptist standards. He soon found that this church was a ‘hornet’s nest of unrest and division.’ His reception was poor and cold. The Executive Committee, a group of seven lay leaders who had micromanaged the church for years, detested Stanley and was determined that he would not become the senior pastor when McClain retired. They particularly disliked his fervent conservative views and biblical preaching and pressured him to resign. When they learned of his Pentecostal roots, they called him a ‘holy roller.’

“They soon brought in other preachers to interview for the pastor’s position. Stanley called them the ‘gang of seven’ that ‘made me feel like an outcast at the church.’ Things came to a head on a Sunday morning in 1971 when Stanley arrived at the church to find that his opponents had put anti-Stanley leaflets on each seat. After the sermon, Stanley gave an altar call. He was surprised to see 300 opponents heading for the exits while 2,000 Stanley supporters came forward to the altar. It was a stunning and overwhelming victory for the embattled preacher.

When Stanley intervened and said that this was improper language for the pulpit, the chairman slugged Stanley in the face.

“In a later Wednesday night business meeting when the church gathered to vote for a new senior pastor, the chairman of the Executive Committee spoke against Stanley’s candidacy and used profanity in his speech. When Stanley intervened and said that this was improper language for the pulpit, the chairman slugged Stanley in the face. Stanley did not respond. Pandemonium broke out as strong men stormed the platform to defend their pastor. When the decision came, Stanley received 65% of the vote.”

A 65% vote is not a good vote in Baptist churches. The bylaws of many Baptist churches require 80% to 90% affirmative votes to call a pastor. But it was enough for Stanley to ascend to the famed pulpit and then to require all Sunday school teachers, church leaders and committee members to affirm in writing that they could serve him as pastor. Anyone not signing was required to resign.

Stanley won the pulpit at the cost of several hundred members who left the church in protest. The largest group of them, reportedly about 200, ended up at Second-Ponce de Leon Baptist Church in the Buckhead neighborhood of Atlanta.

Charles Stanley addresses the 1984 SBC Pastors’ Conference in Kansas City, Mo. (Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archives)

The pastor there at the time was Russell Dilday, who, a decade later, would become a primary target of SBC conservatives.

In 1984, at the very convention where Stanley first was elected SBC president, the convention sermon — an annual highlight — was preached by none other than Russell Dilday, who by then had left Second-Ponce to become president of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas.

Dilday warned against the movement Stanley now represented: “Incredible as it sounds, there is emerging in this denomination built on the principle of rugged individualism, an incipient Orwellian mentality. It threatens to drag us down from the high ground to the low lands of suspicion, rumor, criticism, innuendoes, guilt by association and the rest of that demonic family of forced uniformity.

Four years after his ouster at Southwestern Seminary, Russell Dilday was elected president of the Baptist General Convention of Texas. (Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

“I shudder when I see a coterie of the orthodox watching to catch a brother in a statement that sounds heretical, carelessly categorizing churches as liberal or fundamentalist, unconcerned about the adverse effect that criticism may have on God’s work,” Dilday said.

That sermon cemented Dilday’s favor with SBC moderates but made him a target of the ascending conservative powerbrokers. A decade later, with Southwestern’s trustee board fully in the grip of conservatives, Dilday was unceremoniously fired — an event that echoes through SBC history to this day.

Family drama

Under Stanley’s authoritative leadership, First Baptist Atlanta continued to grow. Church officials say membership peaked at 15,000. Stanley’s influence continued to grow as well, with his face gracing TV screens via perpetual broadcasts of his recorded sermons.

As BNG previously reported, In Touch Ministries — which is separate from First Baptist Church — has assets of $113 million, and Stanley still was drawing an annual salary of more than half a million dollars as recently as last year.

But all was not well at home. Rumors circulated even during Stanley’s SBC presidency that he and his wife, Anna, were estranged.

Their son, Andy Stanley, told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution: “People got used to it, and they quit asking about it. It happened so gradually.”

The rumors became reality in 1993, when Anna Stanley filed for divorce from Charles Stanley. In SBC circles, divorce often ends a pastor’s ministry. But not with Stanley. His devoted followers barely blinked, although he did endure fresh internal challenges to his leadership.

In 1995, Anna Stanley told the Journal-Constitution she had experienced “many years of discouraging disappointments and marital conflict. … Charles, in effect, abandoned our marriage. He chose his priorities, and I have not been one of them.”

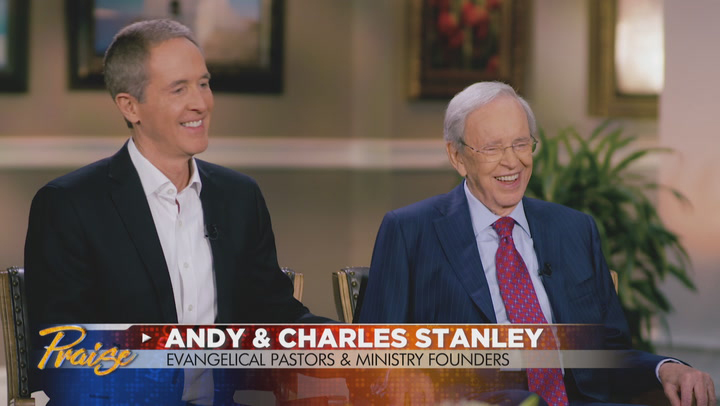

Andy Stanley and Charles Stanley

This marital rift caused a monumental conflict between Charles Stanley and Andy Stanley, who by this time was heir apparent to his father at First Baptist. By then, the younger Stanley shared his father’s pulpit, drawing huge crowds. Later, he became pastor of a First Baptist satellite congregation that also boomed.

The father-son conflict became so strong that Andy Stanley walked away from First Baptist and later started his own church, North Point, a multi-campus congregation that today is the 10th largest church in America.

With help from a counselor, father and son eventually reconciled, but by the accounts of both men, the road was rough.

It is rare for members of the same family — much less a father and son — to grow and preside over two of the largest and most influential churches in America. But that is exactly the legacy of the Stanley family.

Latter years

Charles Stanley

In 1997, Charles Stanley led First Baptist to sell its historic Midtown Atlanta property and move north to the tony suburb of Dunwoody. There, the church that had reported 6,000 in attendance at Easter Sunday services built a worship space for 3,000.

Stanley continued to split his time between leading the church and preaching and writing through In Touch.

In September 2020, with a global pandemic straining churches everywhere, Stanley transitioned to the role of pastor emeritus of First Baptist — having served almost 50 years as senior pastor.

Maina Mwaura

BNG reporter Maina Mwaura, who lives in metro Atlanta, conducted his final interview with Stanley in February 2020, just before the pandemic.

“During my time with him, it was almost as if I was interviewing two different people,” Mwaura recalled. “Stanley’s pastoral features were of kindness and humor. His advice to me on parenting is something that has stuck with me. For example, how he carved out time for Andy and Becky. Although he and Andy went through relationship issues due to his divorce, I was able to back up his words, by asking Andy if he lived up to the advice he gave me, to which Andy said that it is true.”

Mwaura added: “It wasn’t lost on me that he was a man who had a keen sense of self from everything to where we sat for the interview to how we took our picture toward the end of the interview together.

“I also was struck by two important facts regarding Stanley. First, his stance on being a conservative was real. I had just spent time with Paige Patterson a few weeks earlier and mentioned to him my time with Patterson, to which Stanley was clear in saying he thought Southwestern Seminary and the denomination had done him wrong.”

Stanley also noted that on his way to First Baptist, he drives by Second Ponce de Leon Baptist Church and he notices how “dead” the church is.

“It seems he never forgot how a group of members joined Second Ponce due to his takeover of First Baptist Atlanta.”

Stanley is survived by his son, Andy Stanley, and daughter, Becky Stanley Broderson; six grandchildren; two great-grandchildren; and half-sister, Susie Cox. His former wife, Anna Johnson Stanley, preceded him in death.

Related articles:

For SBC, 1984 was the year of the pivot

There’s controversy again, and more people are attending the SBC annual meeting

Bill Self in 1984: ‘Babylonian Captivity of the Convention’

At nearly 90, Charles Stanley makes half a million a year and his ministry is awash in cash

In Touch grants Southwestern Seminary $2 million to endow academic chair named for Charles Stanley