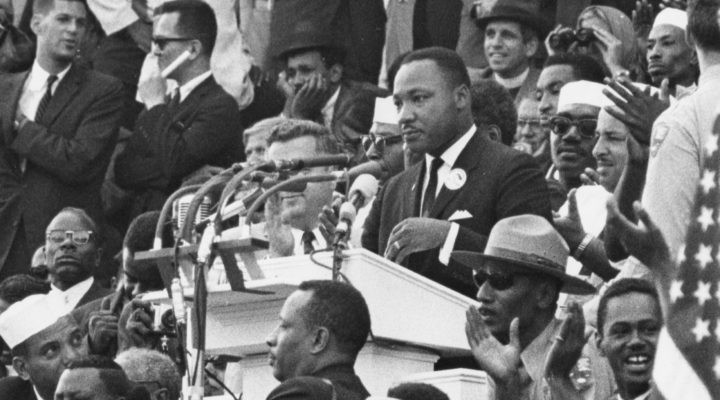

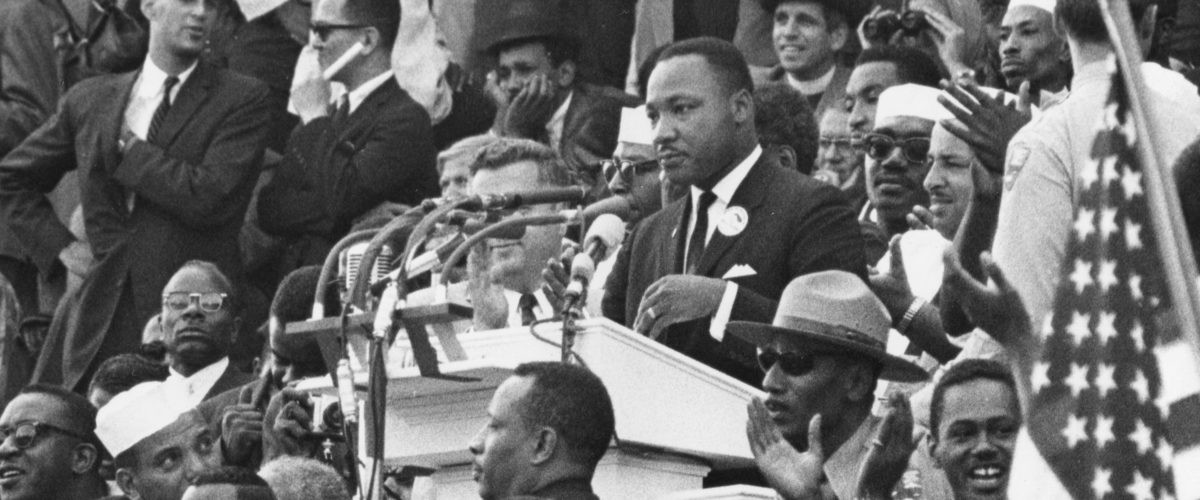

Right there in the middle of the most famous speech in 20th century American history —Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech — was essentially a pipe-dream prayer that King’s “four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Without specifically using the word, King articulated in the movement’s most important speech the concept of color-blindness. It is the concept that launched a thousand — nay, millions of — expressions of vague white defensiveness about and specific denials of accusations of white supremacy: “I don’t see color; I only see the person.”

Andrew Manis

The first public figure to use the term “color-blind” was probably Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan, who in 1897 became the lone dissenter to the court’s stamp of approval on the doctrine of “separate but equal,” which became the basis for 58 years of Jim Crow segregation. Ironically, Marshall also was the only Southerner on the high court when it delivered the ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson. In his ringing rejection of the Yankee majority’s support of segregation, Marshall wrote: “There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind.”

Another Marshall named Thurgood, arguing before the Warren Court, asserted: “That the Constitution is color-blind is our dedicated belief.” Keeping Southern schools segregated was “the color-conscious doctrine of separate but equal.”

In his dissent to the Bakke ruling in 1979, Justice William Brennan opined that, “Government may take race into account when it acts not to demean or insult any racial group, but to remedy disadvantages cast on minorities by past racial prejudice.”

In simple layman’s language, color-blindness in the Constitution is right, proper and just when its purpose is to eliminate discrimination and unfairness. But when its purpose is to remedy the damage done by past discrimination, the Constitution and American society must be conscious of color.

Thus, when the time came to fix what a color-conscious Constitution broke, conservatives twisted the words of King into a paean to color-blindness. The Constitution must be as color-blind in fixing the present results of past discrimination as it was color-conscious in creating and defending those discriminations in the first place.

“When the time came to fix what a color-conscious Constitution broke, conservatives twisted the words of King into a paean to color-blindness.”

In our own day, when someone says, “I don’t see color” to an African American, they are not truly seeing them as persons. Because blackness is integral to their personhood. They cannot live even a day in America without someone or something forcing on them an awareness that they are Black, coupled with the impression that Black is also inferior.

If someone were to say to me, a Greek American, “I don’t think of you as a Greek,” I would assume they thought being Greek was an undesirable trait. If you ignore my Greek descent and heritage, you ignore much of who I am. Being color-blind cannot avoid rendering Black Americans invisible. Being color or culture conscious allows all Americans to be seen.

Of course, where American society today eschews color-blindness most fervently is in the courts. Time after time after time, Kyle Rittenhouses across our nation can cross state lines and carry illegal assault weapons and use them to kill unarmed victims in “self-defense.” And God help us if the killers of Ahmaud Arbery receive the same justice as our newest culture war hero, Kyle Rittenhouse, who as Anthea Butler, author of White Evangelical Racism, rightly predicts, will soon have his calendar full of invitations to mount pulpits for the same “Christians” who bankrolled his defense.

“Can anyone imagine juries in our supposedly color-blind courts rendering the same verdict for the very same scenario if the shooter had been Black?”

Most salient of all is this question to which we all know the answer: Can anyone imagine juries in our supposedly color-blind courts rendering the same verdict for the very same scenario if the shooter had been Black?

If conservatives are going to continue to advocate color-blindness for America, for God’s sake, let them import some of it into our jury rooms. Tragically, conservatives like color-blindness when it is used in defense of racial discrimination, but not in any effort to prove that Black Lives Matter as much as white lives.

Andrew M. Manis is professor of history (retired) at Middle Georgia State University in Macon, Ga., and author of A Fire You Can’t Put Out: The Civil Rights Life of Birmingham’s Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth and most recently, Eavesdropping on the Most Segregated Hour: A City’s Clergy Reflect on Racial Reconciliation.

Related articles:

Dear white people like me, this is what it means to accuse Black people of causing the very crimes committed against them | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

In Wisconsin, the NRA won | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

What’s wrong with saying you ‘don’t see color’? | Opinion by Sid Smith III