I still remember the hot, sticky spit sliding down my frozen face. School had just let out at the elementary school in Yellowknife in Canada’s Northwest Territories. The year was 1963, give or take. I was standing beside a big yellow school bus filled with Indian kids from the Catholic elementary school. (They aren’t called “Indians” anymore; they are the Tlicho, or Dogrib nation, but that’s what we called them.)

When I felt the spit hit my face, I wasn’t sure what it was or where it had come from. Then I looked up. An Indian kid, still wiping his mouth with the cuff of his parka, was pointing at me. He was laughing. Uproariously. So were his buddies.

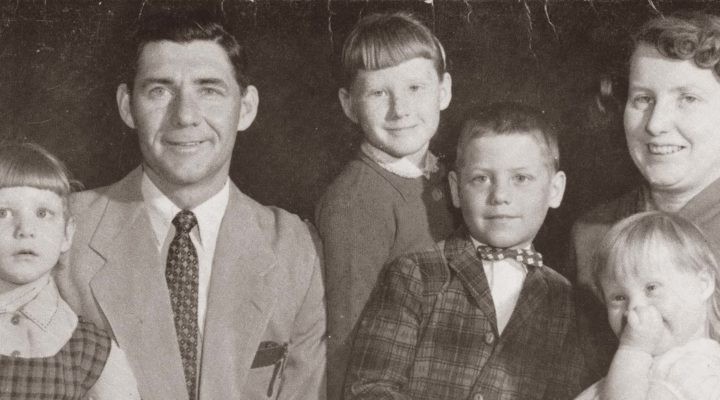

Alan Bean

I was angry, of course. I wasn’t just angry, I was indignant. If the laughing boy knew who I was, I thought, he never would have spit on me. I was a good white guy.

A mix of prejudice and paternalism was the dominant white reaction to the Indian population. I knew that from listening to casual conversation. Every so often, my mother and father would complain about a hateful remark a white acquaintance had made. “All people are equal in the eyes of God,” they told me.

Life in a remote gold-mining town

Yellowknife was a remote gold-mining town of 3,000 when the Bean family arrived in 1956. There was no road to “the outside,” so we flew 1,000 miles north from Edmonton in a WWII-era DC-3. I was 3 at the time, so my earliest memories are of Yellowknife, a town I haven’t seen for 57 years.

In 1958, the government built a row of shacks to house the native population. Local whites already were complaining about the project, my parents said, because “those people” wouldn’t even know what to do with a house. A complete assimilation to white culture was the goal — on that point, all white people seemed to agree.

Most of the Tlicho (Dogrib) people lived in the part of Yellowknife known as the “Old Town” or in little villages scattered along the shores of Great Slave Lake (the 10th largest lake in the world) and as far north as Great Bear Lake (the eighth largest). They sustained themselves by fishing, hunting caribou and, after white settlers showed up, trapping for the fur trade. Dog teams, teepees, parkas, mukluks and snowshoes were basic tools of their trade.

“Local whites already were complaining about the project, my parents said, because ‘those people’ wouldn’t even know what to do with a house.”

Life among the native people

What little I knew about the ways of the Tlicho came from Mark, my best friend. His parents, Bill and June Davidson, lived in the Old Town, where they labored to translate the Bible into the Dogrib (Tlicho) language.

Eventually, Bill and June moved to Trout Rock, a Tlicho fishing village on an island in Great Slave Lake. Trout Rock could be reached only by plane or boat in the summer or, during the eight or nine months of winter, dog team or snowmobile. Mark and his sister, Karin, spent a lot of time among the Tlicho, and Mark’s aspiration was to be a “bushman.” That is, he wanted to hunt, fish and run a trap line just like the Tlicho men he lived with.

For my 10th birthday, I asked for a hunting knife. When I opened the present, it took me exactly two seconds to open a gash between my right thumb and forefinger. I still have the scar to prove it. Mark and I sharpened our broken hockey sticks and stomped off into “the bush” to hunt wolves. In minutes, we stumbled across wolf tracks. Just over the hill, we heard a pack of wolves in full cry. Instantly losing our enthusiasm for wolf hunting, we ran all the way home.

Sample of Tlicho or Dogrib text from the Bible.

Eventually, Bill and June Davidson gave up their translation work. It had been a daunting task. A near impossibility. The native language is so unlike English that a new alphabet had to be created. Then an English-Tlicho dictionary had to be created. Only then could the work of actual translation begin. Eventually, Bill was called as pastor of Calvary Baptist Church, but he maintained contact with his native friends.

Together at camp and church

By this time there was a gravel road to “the outside” and, one summer, Bill and Mark Davidson, two Tlicho boys and I drove 750 miles, one-way, to a Baptist camp in British Columbia. My clearest memory of this experience is that one of the Tlicho boys was put on a horse that decided to wander off into the wooded hills. A search party was organized and, after several hours of anxious hunting, boy and horse were returned to camp. After a week of adventure, we all climbed into Bill’s car and drove back to Yellowknife.

I wanted to communicate with the Tlicho boys, but they only spoke when spoken to, and then only in monosyllables. Their English skills were probably limited, but that never occurred to me. I wanted to show them that, whatever other white people might think, I bore them no ill will. I didn’t say that because it would have sounded weird.

A mid-20th century view looking down into Old Town in Yellowknife with “the Rock” (now Pilot’s Monument) in middle of frame. (Wikipedia)

On Sunday nights, the Davidsons would invite some of their Tlicho friends to join us for worship at Calvary Baptist. One night, Communion was served and, when the tray of crustless bread squares was passed to the Tlicho women, they ate it immediately instead of waiting for everyone to be served. I was horrified by this serious breach of protocol. Then I condemned myself for being judgmental. I didn’t realize that Catholic missionaries, nuns and priests had been working with the Tlicho for a hundred years by the time the Davidsons arrived. The native women, being observant Catholics, were simply following the tradition they had been taught.

With 60 years of hindsight

Looking back from a distance of almost 60 years, I can better understand why the Tlicho boy took such delight in spitting on me. The recent discovery of unmarked graves at residential schools across Canada has rocked me back on my self-righteous heels.

From the early days of Canadian confederation (1867), hundreds of thousands of native children (the proper term now is “First Nations”), including those in the Great Slave Lake region, were forcibly separated from their families and placed in residential schools. The expense was borne by the federal government, but most of these institutions were run by Catholic, Anglican and Protestant Churches.

In 2007, a Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission released a report detailing Canada’s official policy of “cultural genocide and assimilation.” At least 6,000 indigenous children (one in 25) died while attending these schools. These estimates were largely based on oral history interviews. Now, 15 years later, innovative technology makes possible the visual excavation of burial sites without disturbing the ground. The results have been horrifying.

Although physical, psychological and sexual abuse were rife in many of these Canadian residential schools, the mass death of children was typically caused by unhygienic conditions and the spread of disease. Because the federal government was determined to limit expenditures on native education, health care was, at best, an afterthought.

“At least 6,000 indigenous children (one in 25) died while attending these schools.”

Native children were particularly susceptible to disease because they had been uprooted from their families and intentionally moved far from their tribal homes so family members wouldn’t come looking for them. They were punished for speaking their native languages or even referring to tribal customs.

When children died, their families were rarely informed. Children who lived long enough to leave these schools often were unable to communicate with their families. If they wished to vote and gain other perks of settler civilization, they had to formally relinquish their native identity.

The effects of a good white guy

But it gets worse. Sir John A. Macdonald, the Scottish-born “Father of Canadian Confederation,” was the prime architect of this cultural genocide. And Tommy Douglas, the socialist premier of Saskatchewan from 1944 to 1961, perpetuated the disaster. Remembered fondly as “the father of Canadian Medicare,” Douglas was my father’s pastor and Sunday school teacher at Calvary Baptist Church in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, prior to becoming a politician. His stated goal was to “walk in the moccasins of the Indian.”

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau visits a memorial at the Eternal Flame on Parliament Hill in Ottawa that’s in recognition of discovery of children’s remains at the site of a former residential school in Kamloops, British Columbia. (Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press via AP, File)

Like me, Douglas wanted to be the good white guy. But he didn’t regard the indigenous cultures of Canada as being worthy of preservation. It was a zero-sum game in which native culture had to disappear for European settler culture to flourish. Deep down, I shared this assumption.

White Canadians of my generation always have looked down on our bigoted southern cousins. Our ancestors didn’t enslave anybody, we told ourselves. There was no Jim Crow culture in Canada. In order to sustain these beliefs, we have swept our own cultural genocide under the carpet.

For generations my people had been trying to “kill the Indian in the child.” According to native scholar Leroy Little Bear, native children were left with a “jagged worldview.” Aboriginal peoples “no longer had an Aboriginal worldview, nor did they adopt a Eurocentric worldview.” Instead, “consciousness became a random jigsaw puzzle” in which nothing held together.

A better way

Bill and June Davidson modelled a better way. They worked with Wycliffe Translators, an evangelical organization dedicated to the inerrancy of Scripture and the saving of souls. But Wycliffe founder William Cameron Townsend was dedicated to making the world a more just and functional place. For him, that meant fighting to preserve the language, customs and folklore of each distinct culture his organization worked with.

Wycliffe translators like the Davidsons didn’t snatch children away from their tribal roots; they lived with the people, adopting as much of their language and lifestyle as possible. There was no other way to grasp the nuances of a language like Tlicho.

How many 21st century Christians (liberal, conservative or “ex-vangelical”) would be up for a task like that?

The rest of the story

To my childish mind, the Davidsons’ translation work was heroic, even romantic; but how practical was it? I always assumed that their thankless labor came to nothing. But my research uncovered a story that reduced me to tears.

When the Davidsons left the north country, Herb and Judy Zimmerman took their place. In 1981, their work (still far from complete) was featured in the New York Times.

Jaap and Morina Feenstra (Photo from Wycliffe)

When the Zimmermans moved South, Jaap and Morina Feenstra took up the mantle. Their big breakthrough came in 1995, when Jaap approached tribal elders, and, speaking Tlicho with a Dutch accent, admitted that he was a “child in understanding their culture.” From that point on, the translation project became a truly joint effort. It wasn’t long before the Catholic Church, the Canadian government, the Canadian Bible society, a dedicated team of new linguists, and 12 volunteers from the Tlicho community had signed on to the effort.

In 2003, a Tlicho translation of the New Testament and the book of Genesis was published. At virtually the same time, a new treaty between the Canadian government and the Tlicho nation (45 years in the making) was finalized. I would like to think that the translation process gave a boost to the treaty negotiations.

Today, Tlicho children are being educated in their own language, and their parents have assumed full control of all tribal affairs in a land mass as large as Denmark. There was no way the Davidsons, or the tribal elders they worked with, could have foreseen this glorious consummation.

And so, even as each week brings news of fresh graves on the property of long-abandoned residential schools, there is reason for hope.

I just ordered my copy of the Tlicho Bible. I won’t be able to read it, but holding it in my hands will fill me with great joy.

Alan Bean is executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas.