Realism, “the attitude or practice of accepting a situation as it is and being prepared to deal with it accordingly,” compels us to acknowledge we live in a ceaslessly violent time, evidenced by weekly, if not daily, volatile events. The final week of August 2023 was no exception.

On Aug. 26, 2023, a 21-year-old white supremacist, armed with a Glock handgun and an AR-15 swathed in Nazi swastikas, killed three African Americans at a Dollar General Store in Jacksonville, Fla. Earlier in the day, clad in a mask, gloves and bulletproof vest, he was spotted by students at Edward Waters University, Florida’s oldest HBCU. They allerted a public safety officer making his scheduled rounds on the campus, who approached the shooter’s car, causing him to speed away.

He then went to the Dollar General Store, shooting an Uber driver outside, a store clerk and a man entering the store with his girlfriend. When police stormed the building, the shooter took his own life. His computer contained predictable screeds against Blacks and Jews.

Bill Leonard

Waters University President A. Zachery Faison Jr. noted the shooter posted that he “wanted to kill n—–s,” adding, “He could have gone anywhere in Jacksonville. It wasn’t by happenstance that he chose to come to Florida’s first historically Black college. It wasn’t on a whim. He came to where he thought African Americans would be, and that’s Florida’s first HBCU. This is the heart of the Black community in Jacksonville.”

Florida, of course, is the scene of legislative and educational efforts to remove or edit out a variety of details regarding race and racism in American history, limiting or removing curricula deemed to cause students to “feel discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race, color, sex or national origin.” Distress related to school shootings is not mentioned.

Two days after the Jacksonville murders, a graduate student at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, shot his Ph.D. supervisor, Zijie Yan, an associate professor in the Department of Applied Physical Sciences. The 34-year-old shooter was arrested two hours later, but the campus and multiple public schools in Chapel Hill were shut down for several hours.

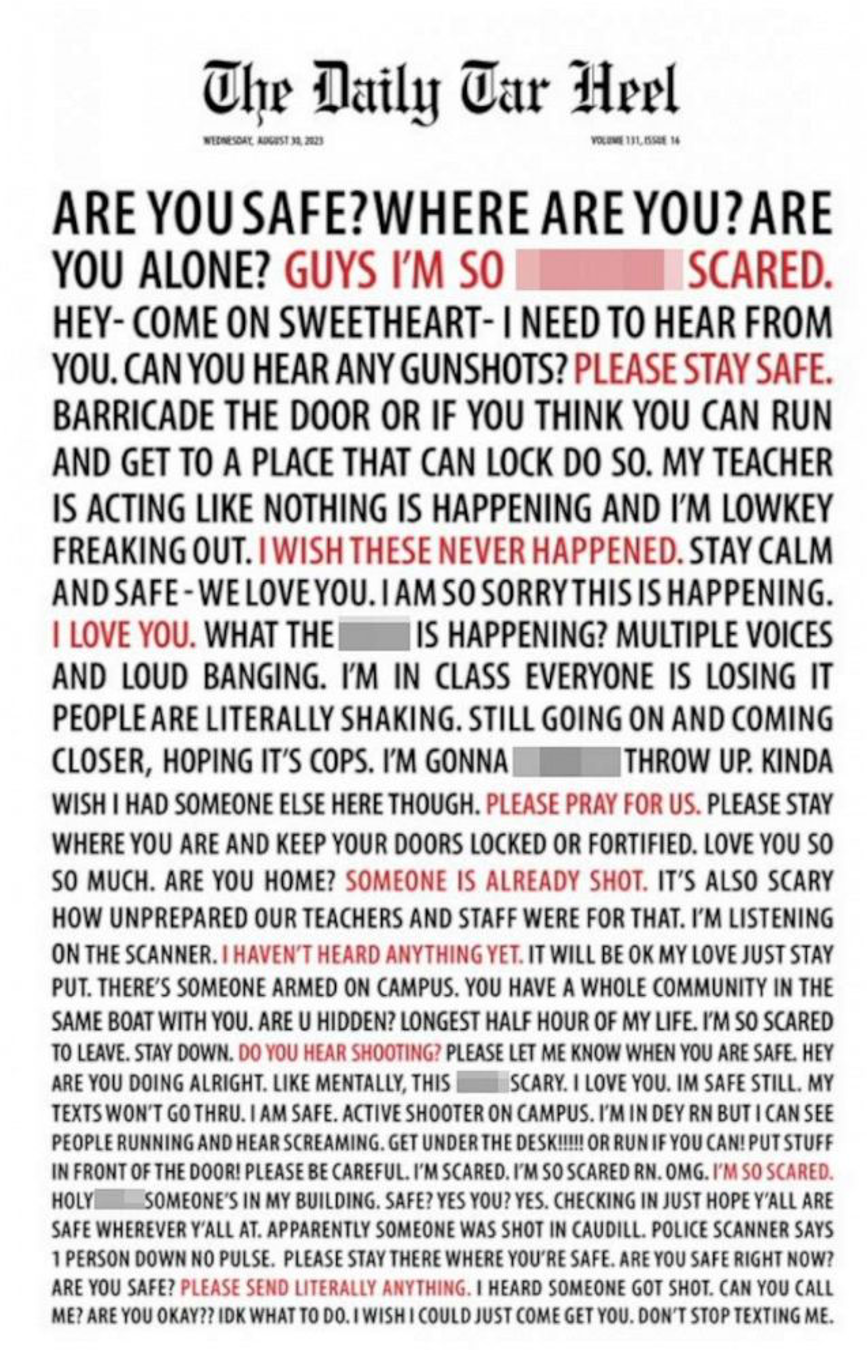

Two days after the UNC shooting, the University’s Daily Tar Heel newspaper produced a front-page collection of text messages sent and received by students during the lockdown, printed in all caps. The chilling dialogue is poignant evidence, not only of the ever-enduring threat of firearm violence, but also the impact of shooter drills and lockdowns. Please read every word of it.

Caitlyn Yaede, the Daily Tar Heel’s print managing editor, wrote, “I definitely think this is the most powerful news interpretation of this event that I could imagine. I don’t think I felt their fear until I saw the paper. I think that was the first time I let down my guard enough to be like, ‘Wow, we all just went through this, didn’t we?’ And what I think is happening across the country is people are resonating with that. These text messages have actually anthropomorphized fear, and now it’s walking around us. And we can’t ignore it.”

Yaede’s realism about the “anthropomorphized fear” reminds us that in this violent culture we are all playing “American roulette.” Anywhere we go in the land of the free and the home of the AR-15 is a potential deathtrap — from the peoples’ Dollar Store to the academics’ Science Building. Likewise, the Daily Tar Heel texts illustrate the fear of that reality can overwhelm us even if we never hear a shot fired.

A recent study suggests even active shooter drills in public education settings is anthropomorphizing fear in a new generation of American children. In February 2023, the Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund announced a partnership with the Georgia Institute of Technology Social Dynamics and Wellbeing Lab (Georgia Tech) in studying the impact of such drills as carried out in 95% of K-12 public school populations. The report suggests:

Active shooter drills in schools are associated with increases in depression (39%), stress and anxiety (42%), and physiological health problems (23%) overall, including children from as young as 5 years old up to high schoolers, their parents, and teachers. Concerns over death increased by 22% with words like ‘blood,’ ‘pain,’ ‘clinics” and ‘pills’ becoming a consistent feature of social media posts in school communities in the 90 days after a school drill. These findings unveil even more reason to pause before rushing toward active shooter drills as a potential solution to school violence, as evidence suggests that they are causing lasting emotional and physical harm to students, teacher and the larger community.

The report includes this observation from a “K-12 teacher:”

I can tell you personally, just as an educator, we were not OK (after drills). We were in bathrooms crying, shaking, not sleeping for months. The consensus from my friends and peers is that we are not OK.

“Rather than take serious action to control the use of guns in our culture, we extend anthropomorphized fear through preventive practices that are inflicting new generations with an American form of PTSD.”

Therein lies another reality of our violent culture. Rather than take serious action to control the use of guns in our culture, we extend anthropomorphized fear through preventive practices that are inflicting new generations with an American form of PTSD, turning schools and other public settings into fortresses that one unlocked door or breakable window can overwhelm.

Our legislators make laws about race, sex, gender and curriculum, to protect students from feeling “discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress,” while consistently ignoring the presence of such distress in relation to our violent gun culture. The result is that gun violence is now a tragic and normative reality in American life and death. (Guns are now the leading cause of death among American children.)

Amid these destructive cultural realities, I keep hearing the words of Psalm 56:3-4:

When I am afraid, I put my trust in you. In God, whose word I praise, in God I trust; I am not afraid; what can flesh do to me?

Meaning the psalmist no disrespect, but “flesh” can do terrible things to us, especially when packing an AR-15. Nonetheless, can the “spirituality” professed by American faith traditions offer a way beyond anthropomorphized fear that surrounds us? For God’s sake we’d better try.

Asking that question, I went back to Spirituality, What It Is and Why It Matters, written by Worcester Polytech philosophy professor Roger Gottlieb, and a longtime friend. He writes, “Spirituality begins in movement — away from what we come to see as unreal, painful, disappointing, trivial, or meaningless and toward the ultimate, true, vital, real or sacred.” A Jewish scholar, Gottlieb acknowledges there are “countless other ways in which spiritual illumination may enter our lives.”

I’m applying his insights to Christianity.

He insists these varying spiritualities share such “common features” as acceptance of reality rather than resistance to it, gratitude rather than greed for more, compassionate connection to other people rather than isolation, and a profound, joyous, nongrasping enjoyment of life.

The spirituality he advocates is at once an internalized relationship with the divine and an external response to injustice, suffering and human need, what I would call an engaged spirituality. Participants in such spirituality work toward those ends, but “they also believe that what they do has value even if they do not succeed.”

“The realities of gun-related violence have taken their toll on children, a vulnerable population for whom the threat of death now seems ever present.”

For Christians, surely an engaged spirituality means we recognize the debilitating cultural realities that confront the church and the nation even as we resist efforts to make them normative. The realities of gun-related violence have taken their toll on children, a vulnerable population for whom the threat of death now seems ever present.

Recognizing those cultural realities, might American Christians ask:

- Are our churches, at least some, willing to bring an engaged spirituality to bear on actual and anticipated firearm-engendered deaths in our community?

- Are we willing to assist families in responding to the anthropomorphized fear created by gun violence in schools and throughout American society?

- Are our churches developing strategies for inculcating spiritual formation in children (and adults) that can help sustain their inner lives amid the anthropomorphized fears that haunt us?

Roger Gottlieb concludes that an engaged spirituality must endure because “we will not surrender to the forces of cruelty and insanity. By some cosmic calculus, it matters what we do. If we believe that, we will have God even in the midst of evil. And we will find God not because of what God does for us, but because of what we try to do for God. In the end, that is all we can be sure of.”

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

Slavery and guns in America: The constitutional parallels | Opinion by Bill Leonard

Yes, there is a way out of our national gun violence epidemic | Opinion by Paul E. Robertson