John Lewis has been called the moral conscience of the United States Congress. His death in July 2020 was a great loss to all of us.

I mourn his death, but I call on his dream, his spirit, for our time now. He believed in and worked for “a beloved community” — a democracy of radical equality and inclusion of every person. And he believed the beloved community was built on a commitment to nonviolence.

For him, nonviolence was the embodiment of God’s love. It wasn’t a strategy. It was the heart and soul of God’s intention for humankind.

Richard Hester

I am calling on the spirit of John Lewis for this time and this election because of his clear and unwavering commitment to nonviolence. And I begin with a scene from the first century.

Two processions

On a spring day in the year 30, two processions came through the gates of Jerusalem almost simultaneously. From the east, Jesus came into the city riding a donkey. He came down the Mount of Olives surrounded by peasants who cheered his arrival and his message about the kingdom of God. A different procession entered the city from the west — Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor, came riding a horse at the head of a column of armed imperial cavalry.

“Jesus’ procession proclaimed the kingdom of God. Pilate’s procession proclaimed the power of empire.”

Jesus’ procession proclaimed the kingdom of God. Pilate’s procession proclaimed the power of empire. These two processions embodied a conflict about power that marked the entire ministry and finally the death of Jesus.[1]

This account from the Gospel of Mark paints in sharp relief the life and work of a peasant teacher who was guided by the spirit and practice of nonviolence. This teacher, Jesus, repeatedly contended with a coalition of Roman power and the power of his country’s religious leaders who collaborated with Rome to control and exploit the peasant population.

Culture of slavery

The church always has had trouble with this scenario. Again and again, it has set aside Jesus’ way of nonviolence in favor of a violent response to any threat. It’s a well-known fact that the pastor of First Baptist Church of Dallas, Robert Jeffress, has declared members of his church are allowed to “concealed carry” and bring their guns to church.

He has said if somebody tries to shoot people in his church, they may get one or two shots off but that is the last thing they’ll do in this life. The implication is that the shooter will be met with a hail of bullets from members of the congregation. Jeffress expresses a striking commitment to violence as the way to respond to violence. His sentiment is not that strange, however, in a nation that is armed to the teeth with guns.

“Our country was born in violence, and the seedbed of this violence is slavery.”

To advocate a stance of nonviolence in this nation is not popular, and it never was. Our country was born in violence, and the seedbed of this violence is slavery. Jeffress’ argument for the protection of his congregation from a shooter is an echo of the logic of the protection of white people from an enslaved population.

In 1860, there were 4 million enslaved African Americans in the United States, almost 13% of the total population of 31.5 million. The constant threat of violence was necessary to enforce this enslavement — to keep slaves from rebelling against their servitude. And the fear of what oppressed slaves could do to their masters kept masters vigilantly armed to protect themselves.

The culture of slavery hovers over every Sunday morning worship service at First Baptist Church, Dallas. But not just there. It hovers over this entire nation every day.

John Lewis (right) with fellow protesters at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., 1965. (Credit: Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group. Photo by Tom Lankford, Birmingham News. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.)

John Lewis’ life

I’m calling on Congressman John Lewis as a person who challenged the ever-present residue of the culture of slavery and the violence that sustained it. Lewis understood Jesus’ philosophy of nonviolence, and he practiced it.

In a 1995 interview[2] Lewis said as a college student he started studying the philosophy and discipline of nonviolence, and in 1960 he began joining nonviolent sit-in demonstrations. Later on, he became a leader in the Civil Rights Movement.

Probably his best known expression of nonviolence was on March 7, 1965, when he was one of the frontline leaders of a march beginning in Selma, Ala., and headed for the capital city of Montgomery to demonstrate African Americans’ right to vote even in the face of a segregationist system that wanted to make it impossible.

“It was the turning point, because there was a sense of righteous indignation when people saw nonviolent people being beaten.”

“That day,” as Lewis described it, “when 600 of us marched through the streets and came to the apex of the Edmund Pettis Bridge, we saw a sea of blue: Alabama state troopers. They told us, in so many words, that this was an unlawful march, that we should disperse and go back to the church. In less than a minute or so, they said, ‘Troopers advance!’ They came toward us, beating us with nightsticks and bull whips, trampling us with horses, and using teargas. I was at the head of the march, as one of the march leaders. I was hit in the head with a nightstick, and I got a concussion right on the bridge. But it was the turning point, because there was a sense of righteous indignation when people saw nonviolent people being beaten. We weren’t armed with guns or sticks. … We were bearing witness to something that we thought was right. We were all committed to the philosophy and discipline of nonviolence.”

Three years later, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on Good Friday, April 4, 1968. At that time, I was pastor of a suburban, white, Parkview Baptist Church in Gainesville, Fla. That following Sunday, I preached a sermon about King to a congregation that included members who saw King as a troublemaker.

At the close of the service, I invited members of the congregation to join me and my wife in a Martin Luther King Jr. memorial march that afternoon. One lone church member joined us. The destination of the march was Mt. Carmel Baptist Church, led by pastor Thomas A. Wright, who also was president of the Alachua County NAACP. Members of the Student Nonviolence Coordinating Committee, SNCC, played a prominent role in the march and in that service. John Lewis had helped organize and had chaired SNCC until 1966.

That event led me to join those who sought to challenge the racial barriers that existed in that city. I became chair of the committee on racial discrimination in an anti-racist organization borne of King’s death — the Coordinating Council of Concern. In that role I partnered with Black employees in a large state facility for people with intellectual disabilities. Hiring and promotion practices there consistently put Black employees at a disadvantage. We were successful in securing the governor’s help to change these practices.

Back then, I did not understand the depth and power of nonviolence. Today’s realities make the spirit of nonviolence seen in the life and work of John Lewis an urgent necessity — lest we sink into the chaos of violence that now threatens us.

Six leaders of the nation’s largest Black civil rights organizations met in New York’s Hotel Roosevelt on July 2, 1963, to plan a civil rights march on Washington. From left, are: John Lewis, chairman Student Non-Violence Coordinating Committee; Whitney Young national director, Urban League; A. Philip Randolph, president of the Negro American Labor Council; Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. president Southern Christian Leadership Conference; James Farmer, Congress of Racial Equality director; and Roy Wilkins, executive secretary, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. (AP Photo/Harry Harris)

Actions more than words

What John Lewis has to tell us about nonviolence is drawn from his actions more than from his words. He developed his view of nonviolence out of the pain and suffering he endured beginning with his lunch counter sit-ins in the 1960s.

About this he says: “I got arrested and went to jail. I remember being beaten and a lighted cigarette being put out in my hair and being thrown off a lunch counter stool before I was arrested, and I had the power because of my belief in Christian love and nonviolence not to strike back.”

He was arrested 40 times during his involvement in the Civil Rights era and five times as a member of Congress.

He recalls the first Freedom Ride through the South — seven whites and six Blacks on his bus to test the U.S. Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation in public transportation. On that trip he ended up being beaten by an angry mob.

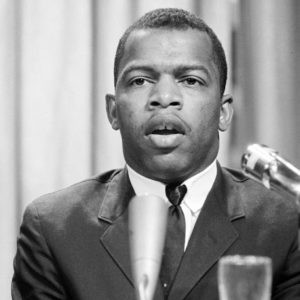

John Lewis, 1964. (Photo by Marion S. Trikosko, U.S. News and World Report, public domain image from United States Library of Congress)

“I was left lying unconscious, bleeding, at a Greyhound bus station in Montgomery in the year 1961,” he testified.

Martin Luther King Jr. was a mentor who taught him, “Love in action is the strongest force, that nothing — nothing — is more powerful than love in action. He taught me to have hope, not to give up, not to give in, and not to give out.”

“It’s very much in keeping with our Christian faith that if you really believe in love you have to live it. When I was working with Dr. King, after a while, I began to believe that maybe, just maybe, we could create the Beloved Community,” Lewis said. “That’s the other thing: It’s possible to create in this life, in this world, a Beloved Society, a Beloved Community, a Beloved World.”

“Nonviolent civil disobedience is a very powerful weapon. It’s probably one of the most powerful weapons that we have in the arsenal of nonviolent action because you’re literally putting your body on the line. You’re saying you’re willing to disobey a custom, a tradition, or what you consider to be an unjust law and you’re willing to pay the price, you’re willing to suffer, you’re willing to go to jail if necessary and serve your time.”

He added: “For me, nonviolence is one of those immutable principles that you do not deviate from. I think there’s something very redemptive about it. In keeping with the philosophy of nonviolent civil disobedience, you come to that point where you have to educate the larger society and you keep trying over and over again, and then sometimes it’s only a core group that’s prepared to go the distance with that.”

Today’s threats

We need to hear John Lewis’ commitment to nonviolence today because of the threats of violence that now besiege our nation. The message and practice of nonviolence is a solvent we can use to counter the toxic poisoning of our culture with violence.

“The message and practice of nonviolence is a solvent we can use to counter the toxic poisoning of our culture with violence.”

- The long shadow of January 6 falls over this election. That shadow contains the shattering events that took place when Trump supporters stormed the United States Capitol, attempting to stop the Electoral College vote confirming the election of Joe Biden as president.

- We now face the threat posed by the possibility that Trump will not win this election but insist that he did, inciting his supporters to repeat the insurrection that occurred January 6.

- Or we face the threat posed by the possibility that Trump will win this election and set about to make good his threats of retribution upon his perceived enemies and his threat that he will deport all undocumented people.

- An increase in hate groups threatens our democracy. The Southern Poverty Law Center has recorded in 2023 the highest number of active anti-LGBTQ and white nationalist groups they ever have recorded. “These record numbers accompany increases in direct actions against minoritized groups.”[3]

Beneath all these threats lies the fear of the loss of the power and privilege of white supremacy.

This is a deeply rooted fear that has been instilled in the national DNA by the institution of slavery and the subsequent systemic oppression of Black people.

Robert P. Jones, in his book White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity, describes how this fear in the national DNA has been transmitted. “White Christian churches have not just been complacent; they have not only been complicit; rather, as the dominant cultural power in America, they have been responsible for constructing and sustaining a project to protect white supremacy and resist Black equality. This project has framed the entire American story.”[4]

Back to Jerusalem

I began this article with the statement that Congressman John Lewis is my choice for this election. He is my choice because of his unwavering commitment to nonviolence. Let’s return here to Jesus in the year 30 CE and his nonviolent challenge to the powers that be in his country.

Jesus sees the inevitability of his death as he challenges the leaders of the temple who are collaborating with the Roman occupation of their country. He has told his disciples he is facing a showdown with these leaders who are puppets of Rome and he is going to be executed.

The disciples don’t grasp Jesus’ message of nonviolence. They are expecting a violent showdown in which Jesus will end up leading the way to a military victory.

This expectation leads James and John to make a brash request: “Grant us to sit, one at your right hand and one at your left, in your glory.” Their request reveals clearly their expectation that Jesus will be a victor in the looming conflict with the temple authorities and, more than that, that he will be successful in a military campaign to overwhelm the Roman occupation forces.

The other disciples become angry with James and John for trying to steal positions of power with Jesus in his kingdom. Jesus cuts off this attempt with these words: “You know that among the Gentiles those whom they recognize as their rulers lord it over them, and their great ones are tyrants over them. But it is not so among you; but whoever wishes to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be slave of all. For the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many.”

This has to be one of Jesus’ most striking self-descriptions. Nonviolence isn’t a strategy of Jesus. It is an expression of who he is. It is one way of saying he is the embodiment of God’s love.

John Lewis got it right: Nonviolence is an expression of Jesus’ love. This means, of course, that if God is love like this, then God is a nonviolent being — the many biblical narratives to the contrary notwithstanding.

These violent biblical narratives are the seedbed for what Walter Wink has called “the myth of redemptive violence”[5] — the myth that violence will bring peace, that it will get us the world we want, that all will be well once we win with violence. John Lewis’ spirit tells us this is not the truth, that the Beloved Community is created through the persistent courage of nonviolence.

Richard Hester is professor of pastoral theology, retired, from Phillips Theological Seminary, Tulsa, Okla. and Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, Wake Forest, N.C. He led the Southeastern Seminary faculty opposition to the fundamentalist control of the school. He completed his career as senior therapist at Triangle Pastoral Counseling, Raleigh, N.C., where he established the Narrative Therapy Seminar. His forthcoming book, Theological Education in a New Key: Narrative, Belonging, Diversity, is to be published in January 2025.

Related articles:

Remembering John Lewis: An invitation to make ‘good trouble’ | Opinion by Aidsand Wright-Riggins

History will judge both John Lewis and Donald Trump | Opinion by Rob Sellers

Notes:

[1] Marcus J. Borg and John Dominic Crossan, The Last Week: What the Gospels Really Teach about Jesus’s Final Days in Jerusalem (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2006), 2.

[2] In 1995 Rev. John Dear interviewed John Lewis. In 2021 he recovered that interview and published it in Waging Nonviolence: People Powered News & Analysis, March 3, 2021. All the quotes by John Lewis I’ve drawn from that interview.

[3] Rachel Carroll Rivers and Eric Ward, Decoding the Plan to Undo Democracy: The Year in Hate & Extremism 2023, Southern Poverty Law Center (Montgomery, AL, 2024).

[4] Robert P. Jones, White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020), 6.

[5] Walter Wink, The Powers that Be: Theology for a New Millennium (New York: Doubleday, 1998), 42-62.