With the death of Queen Elizabeth II on Sept. 8, her heir, Charles, became King Charles III. Accompanied by grief and grateful tributes from around the world, Elizabeth II’s death marks the end of a lengthy era of British history (veritably a second Elizabethan age) and the beginning of as much uncertainty as certainty.

Within one week, a new prime minister occupied 10 Downing Street with incredible economic pressures at hand, and the new sovereign began the delicate work of leading national grief and mourning while also beginning his reign finally at the age of 73.

Given the certainty of his coming time as king, the speculation of what type of monarchy Charles III would oversee has been going on for years in the British press. His every comment, genteelly aimed at not saying much of anything that would be seen as contrary to his mother’s ways, still made headlines.

At one point, he commented to an interviewer that he saw his coming time as king as an opportunity to be “Defender of Faith,” which led to some reading the title as a revision of the historic royal title of “Defender of the Faith,” referring to the British crown’s headship of the Church of England. Popularly, the phrase often was misquoted as Charles seeking to be a “defender of the faiths” (plural).

In 2015, this matter came up again in an interview where Charles addressed his earlier comment:

“I tried to describe, I mind about the inclusion of other people’s faiths and their freedom to worship in this country.”

No, I didn’t describe myself as a defender: I said I would rather be seen as ‘Defender of Faith’ all those years ago because, as I tried to describe, I mind about the inclusion of other people’s faiths and their freedom to worship in this country. And it’s always seemed to me that, while at the same time being Defender of the Faith, you can also be protector of faiths.

It was very interesting that 20 years or more after I mentioned this — which has been frequently misinterpreted — the queen, in her Jubilee address to the faith leaders, said that as far as the role of the Church of England is concerned, it is not to defend Anglicanism to the exclusion of other religions. Instead, the Church has a duty to protect the free practice of all faiths in this country.

I think in that sense she was confirming what I was really trying to say — perhaps not very well — all those years ago. And so I think you have to see it as both. You have to come from your own Christian standpoint — in the case I have as Defender of the Faith — and ensuring that other people’s faiths can also be practiced.

While the era of Charles III is just unfolding, it will be interesting to see how he brings such thinking into practice. A growing respect for religious and cultural pluralism certainly was a mark of Queen Elizabeth’s long reign, yet so was the country’s long colonial history that has inflicted much harm and often distorted the gospel’s aims and purposes.

While I believe time heals all wounds, we must contend with the lingering marks and traumas of those wounds, which necessarily is the work of generations after we have “ended” an era.

“We must contend with the lingering marks and traumas of those wounds, which necessarily is the work of generations after we have ‘ended’ an era.”

While I wish Charles III a long reign and the American democratic experiment an even longer life, I find myself intrigued and amazed at how times change, yet how the need to defend the faiths is not only the work of the crown or seat of government, but also very much in our own convictional DNA as Baptists.

If anything, Charles III’s ponderings of his role as Defender of the Faith including all faiths practiced within the realm is a far cry from the attitudes of the British crown around the time of the Baptist tradition’s origins in the late 16th and early 17th century. The shadow side of the crown and the church certainly includes its exclusion and intermittent toleration of religions outside of the church.

For good reason, you will find the great Baptist pastor and writer John Bunyan buried in a dissenter’s cemetery in London, alongside other dissenters such as Daniel Defoe and William Blake. While they are rightly hailed as great voices of their era, the church and crown of their day considered them “outside” the proper realm of faith and society.

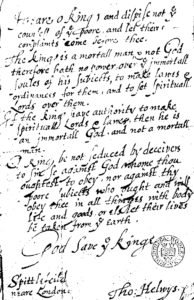

Further, the earliest Baptists formed their distinctive identity while living in exile in the more religiously tolerant Amsterdam. Among their number was Thomas Helwys, who wrote the first apology for universal religious freedom, taking aim at the church and crown. Titled A Short Declaration of the Mistery of Iniquity, Helwys wrote a scathing critique of the religious and political landscape of England. A copy was sent to King James (yes, the King James of the Authorized Version beloved by some Baptists as “the” English translation to have in hand and pew rack alike). Helwys wrote an inscription to the king in a presentation copy sent to the court:

Heare, o King, and dispise not the counsell of the poore and let their complaints come before thee. The king is a mortall man and not God, therefore hath no power over the immortall soules of his subjects, to make lawes and ordinances for them, and to set Spiritual Lords over them. If the king have authority to make Spiritual Lords and lawes, then he is an immortall God, and not a mortall man. O King, be not seduced by deceivers to sine so against God whome thou oughtest to obey, nor against thy poore subjects who ought and will obey thee in all thinges with body, life and goods, or els let their lives be taken from the earth. God Save the King.

Heare, o King, and dispise not the counsell of the poore and let their complaints come before thee. The king is a mortall man and not God, therefore hath no power over the immortall soules of his subjects, to make lawes and ordinances for them, and to set Spiritual Lords over them. If the king have authority to make Spiritual Lords and lawes, then he is an immortall God, and not a mortall man. O King, be not seduced by deceivers to sine so against God whome thou oughtest to obey, nor against thy poore subjects who ought and will obey thee in all thinges with body, life and goods, or els let their lives be taken from the earth. God Save the King.

Shortly thereafter, King James (yes, that one!) tossed Helwys and others from his church into prison. In 1616, Helwys died in jail.

Time has passed since Thomas Helwys’ early advocacy for religious freedom, joined a few short years later by the emerging Baptist voices of Roger Williams and his generation, influencing the development of church-state relations in America and the somewhat mixed historical record (on both sides of the Atlantic) of religious diversity and religious minorities being treated with the deference Charles III articulates today. (Indeed, a few Baptists have sometimes remembered — and sometimes forgotten to remember — their roots when it comes to respecting “otherness,” especially in the public square, when their own social and political voices strengthened over the course of US history.)

While I wish Charles III a long reign and the American democratic experiment an even longer life, I find myself intrigued and amazed at how times change, yet how the need to defend the faiths is not only the work of the crown or seat of government, but also very much in our own convictional DNA as Baptists.

Jerrod H. Hugenot

Jerrod H. Hugenot serves as associate executive minister for American Baptist Churches of New York State. This article originally appeared in The Christian Citizen and is republished here with permission.

Related articles:

King Charles should abolish the term ‘Defender of the Faith’ | Opinion by Michael Friday

Womanhood, white Christian nationalism and Queen Elizabeth | Opinion by Greg Garrett

Reflections from London on the queen’s life and death | Opinion by Ella Wall Prichard