I was a junior in college, studying religion and serving as a youth minister when I first encountered the Southern Baptist Convention’s vitriol against women. Although a Southern Baptist church employed me, a not-yet-out queer woman, as a youth minister and another woman as music minister, controversy stirred over women in ministry.

Angela Yarber

This controversy — complete with physical shoving, a deacon breaking into the parsonage where I lived, and a lot of name-calling — led to a church split. At the ripe age of 20, I helped start a new church in a tiny South Georgia town, a church committed to ordaining and affirming women in ministry. There, I preached and presided at Communion, and we all left the Southern Baptist Convention, affiliating instead with the moderate and women-affirming Cooperative Baptist Fellowship.

This was more than 20 years ago, solidly after the SBC’s passing of resolutions against women in ministry, and decades past the genesis of this fight in Baptist life.

But the story doesn’t end there for me. Another Baptist church ordained me, and after seminary I hitched my hopes to a U-Haul and headed west to pursue a Ph.D. in Berkeley. There, like so many closeted women from the South, I came out as queer, met my wife, fell in love, and my relationship with both the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and American Baptists became a bit more tenuous.

“The same denominations and churches that hung their hats on the ordination of women employed the SBC’s exclusionary tactics to dismiss the ministry and ordination of queer folx like me.”

You see, the same denominations and churches that hung their hats on the ordination of women employed the SBC’s exclusionary tactics to dismiss the ministry and ordination of queer folx like me. In a long and sticky coming out process, I found welcoming and affirming Baptists, like the Alliance of Baptists, Association of Welcoming and Affirming Baptists, and Baptist Peace Fellowship.

I even became pastor of the first and, at the time, only Baptist church in the world with two out lesbians as head pastors. As churches are wont to do, this seemingly affirming place became toxic too. But it wasn’t the stacks of hate mail or even death threats from outsiders that caused me to leave. Rather, it was the homophobic microaggressions from within the very community that called me.

After nearly 15 years as a Baptist pastor, I left the institutional church in search of a spirituality that was deep and expansive enough for all. For a decade, I led retreats rooted in queer spirituality, taught courses about queer spirituality, researched and painted revolutionary queer women of color who have paved the way.

And now, as a response to more than 460 bills proposed restricting LGBTQ rights, all fueled by the same white Christian nationalism that excludes women and queer folx from ministry, I’ve partnered with Paige Rawson in launching a Queer Spirituality Ministry.

Queer Spirituality aids queer folx in recovering from religious trauma, restoring the voices of queer saints, and reimagining a spirituality rainbow enough for all. Individually and collectively, we have been damned, banned, excluded and traumatized by institutional religion; these religions must repent and ask our forgiveness and, together, we can heal from this trauma.

After recovery comes the restoration of queer saints. Hidden in the crevices of our cannons are revolutionary queer saints who have led rituals, surrendered to Allah, prayed to Yahweh, preached of Jesus, meditated with Buddha, danced alongside Shiva and guided our spirituality for millennia.

Once we recover from religious trauma, we can restore the forgotten stories of queer spiritual leaders. This is the work of many reconciling ministries from across wisdom traditions who are committed to the full inclusion of LGBTQ people in spiritual leadership. But that, I believe, is not enough.

“It’s not enough for queer people to have to reconcile ourselves to the traditions that once traumatized us.”

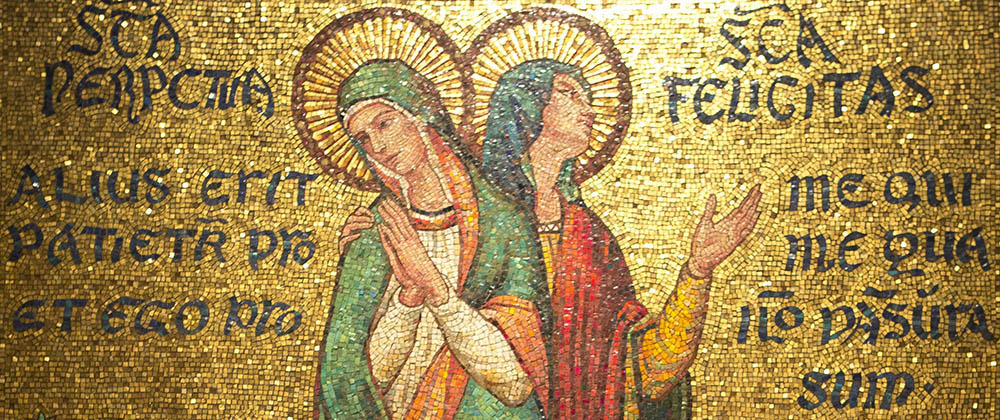

It’s not enough for queer people to have to reconcile ourselves to the traditions that once traumatized us. Rather, queer spirituality empowers us to reimagine what faith looks like altogether. This reimagination functions both inside and outside existing religious traditions. Inside, Buddhists reimagine Guanyin, the Buddhist goddess of compassion and mercy, as a trans icon because of her gender fluidity. And Catholics reimagine Perpetua and Felicity, not simply as third century martyrs for the faith, but as patron saints of same-sex marriage because of the mutual love recorded in their diaries and how they held one another and kissed while being stoned to death.

Outside institutional religion, queer spirituality reimagines something altogether different than queer religion. The innate spirituality of queer folx creates alternative rituals where the club is our chapel, the rainbow flag and the virtues it represents, our sacred symbol, renaming ceremonies of our trans kindred, our baptism or mikveh, Pride, our holiest of days, and our chosen families, our faith community. Our meditation is liberation. Our prayer, authenticity.

When I think back to my 20-year-old self fiercely battling with the SBC as a fledgling congregation invited me into their pulpit to preach, I cannot help but wonder how queer spirituality would have revolutionized our community. Embracing a queer spirituality certainly would have freed me from years of anguish, self-doubt and self-loathing.

And I am convinced queer spirituality has the power to cast a rainbow over all people, communities and institutions, transforming them into safe and brave spaces committed to celebrating diversity, radically imagining — and creating — heaven on earth.

Angela Yarber is an author, artist, professor and retreat leader. With a Ph.D. in art and religion, five of her eight books are listed in QSpirit’s Top LGBTQ Religion Books, and she co-facilitates Queer Spirituality Ministry. Her work has been featured in Forbes, HuffPo, the Independent, Ms. Magazine, and the television show Tiny House Nation. For more, visit www.tehomcenter.org