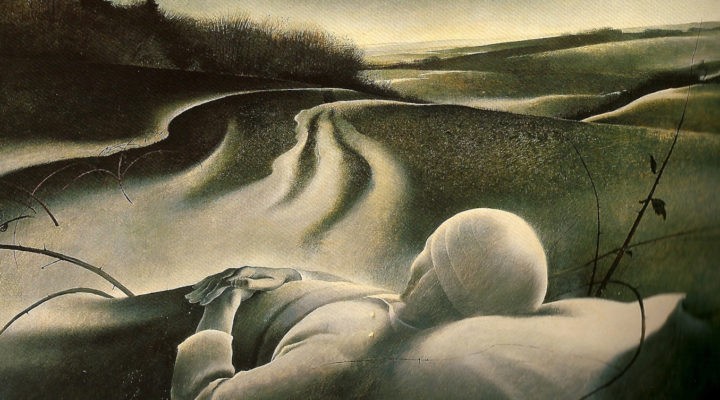

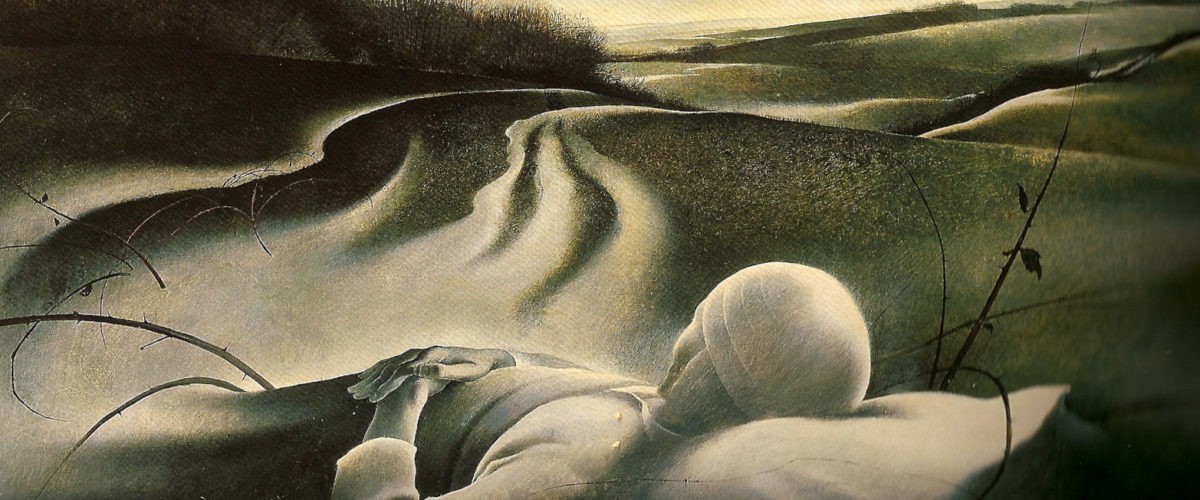

As the school year ends and I try to process the many agonies of the annus horribilus COVID year of 2020-21, I will remember many deaths, but most especially the death of my father in late December 2020. These posts, adapted from my forthcoming book, Introducing Christian Ethics, are offered in his memory and shaped by my experience of his death.

Every living thing eventually dies. It is not just the inevitability of death but the nature of our awareness of it that does so much to determine the meaning of human existence. We live toward our own death. We live knowing that everyone we love also will eventually die.

David Gushee

Even in a pandemic, this staggering information is not fully assimilable. Much of the time we try not to think about it. That becomes more difficult as we age, not just because we know we are moving toward death but also because death gradually comes nearer to us in the loss of our family members and eventually our siblings and friends.

Moral questions that emerge at the end of life challenge all ministers and all ethicists. As I look back on my own earlier writing about end-of-life issues, I see my youthful distance from death. The first edition of the Stassen/Gushee Kingdom Ethics textbook came out almost 20 years ago. I wrote the discussion of end-of-life issues in that volume. As I look at that chapter now, it feels abstract and theoretical. That younger me offers the relevant terms and concepts but has little feel for the agony of the dying and of their families.

The four posts I will offer over the next several weeks are written from a different place. Since 2014 I have now buried my mother, father-in-law, mentor, sister, and father. I am beyond grateful that I did not also bury a child, two of whom had near-misses, or a wife, who has had two threatening conditions. Yes, indeed, death has come much nearer to me since 2003.

“Since 2014 I have now buried my mother, father-in-law, mentor, sister, and father.”

I am convinced that a distinctively Christian approach to ethics at the end of life can be identified and must be protected today, at least for followers of Jesus. But I am also convinced that it is vulnerable both to technological advances and the fading influence of Christian theology in Western cultures. I want to clarify what I believe to be some moral red lines and some best practices. This will be my goal in this series of posts.

* * *

Technological advances have fundamentally altered the context in which moderns think about all kinds of moral issues. Consider how much has changed at the beginning of life, as modern birth control, reproductive technology and abortion all represent technological interventions related to human procreation and aimed at maximizing human choice and control. But these technologies have proved only partially successful in giving human beings that desired control.

Something similar — although not identical — can be said about the end of life. Especially in the rich world, dramatic advances in nutrition, lifestyle, medical care, pharmaceuticals, public safety, hospital practices and other factors have dramatically extended the life span. Likewise, medical and technological advances constantly gain victories for life against death, sometimes even defeating scourges like cancer, and certainly extending living — and dying — far longer than our ancestors could have imagined.

These advances have changed the context in which most people in modern societies live their final days. In the United States, despite 80% of people expressing a preference to die at home, only 20% do so. Of the rest, 60% die in hospitals and 20% in nursing homes. The dying process has been medicalized, and so the context of dying has changed from home to institution, mainly the hospital.

“In the United States, despite 80% of people expressing a preference to die at home, only 20% do so.”

I can say from experience that when a family member dies in an institutional setting the family can often experience a profound loss of privacy and control. Strangers intrude during some of the most important, intimate and painful moments in a person or family’s entire life.

These losses are accepted as part of the price of fighting death with the best means available. But it is still true that death wins, 100% of the time. Medicine and technology have proved only partially successful in defeating disease and giving human beings longer lives. They have been and presumably always will be completely unsuccessful in defeating death, until Christ wins the final victory over death as promised in Scripture.

What modern medicine clearly has been able to do, however, is to take over the dying process for most people. This includes offering treatment options for conditions that once would have been considered irremediable. Medicine also can keep people alive who, in the past, would have died far earlier. But also, medicine can go in the opposite direction to offer options for hastening or directly causing death, if that is what is sought. What we ask medicine to do for us at the end of life — if anything — is entirely a human choice.

“The problem is that many times those in the grip of a medical crisis are swept up in a system that dwarfs and overwhelms them.”

That is where ethics comes in, or should come in. The problem is that many times those in the grip of a medical crisis are swept up in a system that dwarfs and overwhelms them. It ought to be a goal of thoughtful Christians today to wrestle back some control over the dying process and some space to make real decisions rather than be swept along by the momentum of others’ decisions.

In the case of my father, although he was not dying of COVID, we learned that because of COVID he was likely to die inaccessible to us if we did anything other than in-home hospice care. Given the horrible alternatives, under intense time pressure to decide, that is what we chose.

Doing home hospice care dramatically altered our experience of my father’s last days. No medical professional and no institution stood between us and the dying process of our father. Indeed, I would say that we received minimal help and often felt terrifyingly alone. And yet, it was for the best. I will say more why I believe this in my next post.

David P. Gushee is a leading Christian ethicist. He serves as Distinguished University Professor of Christian Ethics at Mercer University and is the past president of both The American Academy of Religion and The Society of Christian Ethics. He’s the author of Kingdom Ethics, After Evangelicalism, and Changing Our Mind: The Landmark Call for Inclusion of LGBTQ Christians. He and his wife, Jeanie, live in Atlanta. Learn more: davidpgushee.com or Facebook.

Related articles:

When the dying stops, will we remember to address the multiplied grief of COVID?

We need to talk about dying | Opinion by Brett Younger

‘Will it come like this, the moment of my death?’ Living and dying in a COVID-19 world | Opinion by Bill Leonard

My Coronavirus Summer: Coping with grief and seeking joy | Opinion by Ella Wall Prichard