Not long ago, our evangelical brothers (and some sisters) seemed to like this passage a lot. So did the previous presidential administration.

“Let every person be subject to the governing authorities; for there is no authority except from God, and those authorities that exist have been instituted by God …” (Romans 13:1).

This seems pretty clear. Even if you were convinced the 2020 election had been stolen (it was not), it is still hard to escape the arguments pastors and officials associated with the former administration. I was told the following on several occasions:

“The president is in power because God has ordained it.”

“That’s what the Bible says (Romans 13:1). Deal with it.”

Interestingly, this argument has been silent for the last four years. Biblical history can teach us some valuable lessons. Let’s begin with the Bible itself.

The biblical context

Paul probably composed Romans sometime between 57 and 58 AD during the reign of Nero (who ruled 54-68 AD). While Paul was preparing his letter and advocating holy respect for ruling authorities, the Roman world was relatively calm.

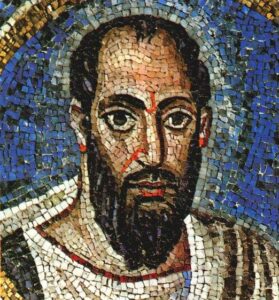

A mosaic of the Apostle Paul from the 5th century CE in Ravenna, Italy.

Paul’s primary concerns to this point had come from Jewish religious leaders arguing with him over the nature of Jesus, the primacy of the law and the status of Gentiles. Roman soldiers and government officials often had been his allies (he was a Roman citizen after all, along with other early Christians like Silas and perhaps Luke).

Emperor Nero had remained a kind of odd sideshow. He was narcissistic, immature, unconcerned with the broader world, unaware of what he didn’t know, incompetent, impulsive and mostly distracted in his early years of being emperor. He viewed himself as an artist, singer and composer.

He wanted and got large crowds of “adoring” spectators. The subsequent rave reviews expected by Nero barely hid the truth. He was mediocre at best but so taken with pretended responses he began to broaden his exploits to athletic contests. We are told he won races he wasn’t even in. He reveled in the fawning, awards and pretense.

When Paul composed Romans, Nero had been a strange, emperor-clown most laughed at behind his back. Few took him seriously. The wise and highly competent philosopher Seneca (who tutored Nero and ran the affairs of state from 54 to 65 AD) was the real power behind the throne. And the empire was run by enough other competent officials. Life went on, the economy thrived and the Christian church continued to grow. Until everything changed.

“When Paul composed Romans, Nero had been a strange, emperor-clown most laughed at behind his back. Few took him seriously.”

In the summer of 64 AD, fire raged through Rome. Dry weather and hot winds carried embers, ash and flames over two-thirds of the famous city. Countless lives, priceless works of art, vital historical documents and untold architectural wonders were lost in the conflagration.

Suspicions leaned in the direction of Nero (he “fiddled while Rome burned,” it was said). His desire for expanding his palace fanned rumors. A quick move to construct the palatial “golden house” in an area close to where the fire began led many to believe he had the fire set as a prelude to his personal urban renewal.

Anger grew. Nero, never one to admit to mistakes, quickly looked for distractions and for others to blame.

It was the Christians, he declared, this growing rabble of unpatriotic, potentially seditious underclass. Tacitus, the famous Roman historian, shares what came next:

Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called “Chrestians” by the populace. … Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind. Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired.

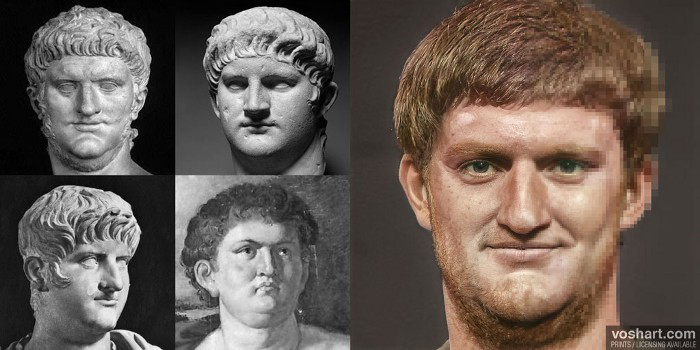

A photorealistic reconstruction of what the Roman Emperor Nero may have looked like. Pictured alongside the reconstruction are the artworks and statuary used as references. From left to right and top to bottom these are the Capitoline Nero; the Glyptotek bust; the Uffizi Gallery’s bust; and the painting by Peter Paul Rubens.

Christians learned a lesson

From these horrors, Christians understandably began to view the empire and those who ran it with far more concern. Although Nero’s persecution was localized to the areas right around Rome, the ramifications for Christians across the empire were profound.

“Would Paul’s perspectives in Romans 13 have been different had they been written after 64?”

At the time of the fire, both Paul and Peter were in Rome. Both are believed to have been martyred soon after. Paul was beheaded. Peter was crucified upside down. Would Paul’s perspectives in Romans 13 have been different had they been written after 64? We’ll never know. But we do know history.

Nero was forced to take his own life in 68. The oddities and tragedies of his bizarre reign eventually yielded to the more competent, professional leadership of Vespasian (who ruled 69 to 79) and Titus (who ruled 79 to 81). Both died natural deaths after successful reigns. Then came Titus’ brother, Vespasian’s other son, Domitian (who ruled 81-96).

For Christians, Domitian became the new Nero. Domitian, like Nero, was a spoiled, narcissistic playboy. Similar to the latter years of Nero, Domitian began to rule with increasing paranoia, violence and progressively unpredictable decision-making. The worse his behavior, the more Christians perceived the crumbling of Roman authority.

What had been appreciated by Paul (a Roman citizen) and prized by Luke (the author of Luke and Acts and a highly educated Gentile) the Empire’s moral bankruptcy is suddenly laid bare in the early 90s AD:

“Fallen, fallen is Babylon the great! It has become a dwelling place of demons, a haunt of every foul and hateful bird … for all the nations have drunk the wine of her fornication …” (Revelation 18:2-3).

The book of Revelation speaks truth to imperial power. Likely composed between 93 and 95 AD during the reign of Domitian (81-96 AD), this well-crafted work of apocalyptic literature becomes a biblical response to devolving Roman power. Throughout, Revelation unveils what Paul in Romans 13 had not yet fully experienced.

In the 40 years from the writing of Romans to the composition of Revelation, Christians confronted a vastly different world of governmental affairs. No longer could anyone in the struggling but growing Christian community view the emperor and his power as malevolent.

This Beast of Revelation is evil incarnate. In this part of the Bible, Imperial Rome no longer remotely resembles the God-sanctioned authority Paul spoke of in Romans 13.

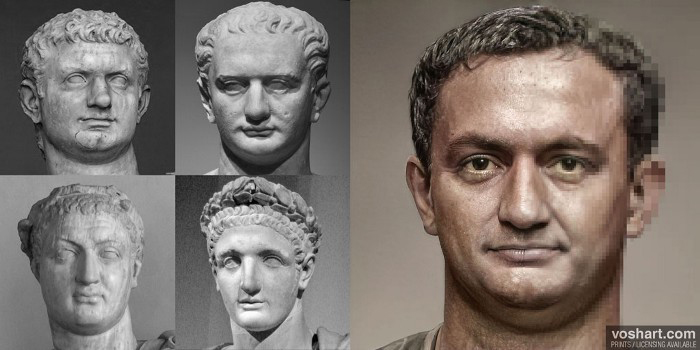

A photorealistic reconstruction of what the Roman Emperor Domitian may have looked like. Pictured alongside the reconstruction are the artworks and statuary used as references. From left to right and top to bottom, these are the Vatican bust; Altes Museum Berlin bust; National Archaeological Museum of Venice bust; and the Louvre bust.

Lessons from history

The separation of church and state makes sense: This is but one of the many healthy lessons we can glean from our Christian history. So while evangelicals like to quote Romans 13 when their leaders have ready access to governmental power, accurate readings from the past offer formidable insights and better wisdom. Churches work fine when left alone to divine inspiration. The state is best when we Christians do our civic duty as faith inspires; and, remembering history, we fully respect the faith of others.

- Context matters. So does our application of the Bible. Never should any of us use Romans 13 to excuse governmental overreach. Nor should we acquiesce to authority unethically wielded. And while Revelation never advocates violence, it does call for perceptive understanding and a faithful response.

- Humility and kindness are essential. With the ever-present dangers of reckless, thoughtless power, humility and kindness remain eternal values. The Bible, and especially Jesus, advocates these from the very beginning.

- Narcissistic playboy emperors are no joke. They can quickly morph into wicked, demented rulers. Those early Christians concluded Domitian and the broader empire could be creatively imaged as Nero incarnate and the Beast embodied. The Jewish gematria number 666 still stands for the pretender, the one posing as a pseudo savior, a liar who masks evil intent with popular slogans and rising power. Therefore, be on guard.

Taking Scripture seriously, let us learn from what has been; and let us apply it rightly to what is now; and let us be prepared for all that is yet to be.

David Jordan

David Jordan serves as senior pastor at First Baptist Church of Decatur, Ga.

Related articles:

Out of context: misunderstanding Romans 13 | Opinion by Matthew Tennant

Thinking biblically about government in an election year | Opinion by David Gushee