Reaching herd immunity against the coronavirus cannot happen without more intervention from the faith community, according to leaders of two national organizations tracking current trends.

“We do not get to herd immunity without dealing with faith identity. Religious identity is key to ending the virus,” said Eboo Patel, founder of Interfaith Youth Core. “There are significant segments of the American community whose attitude toward the vaccine is tied to their religious identity.”

IFYC partnered with Public Religion Research Institute to conduct the largest national survey to date exploring religious identity and vaccine hesitancy. The two groups reported findings of the survey in a webinar April 22.

“Religious identity is key to ending the virus.”

“America’s religious congregations can be a powerful tool for convincing hesitant Americans to get vaccinated,” added Robert P. Jones, founder of PRRI.

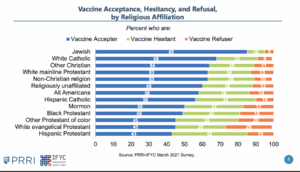

Faith communities and especially faith leaders can make a notable difference among the vaccine hesitant, who account for 28% of all Americans today. And although those who are vaccine refusers — representing 14% of all Americans and the most hard-core opponents of vaccination — are harder to reach, faith leaders can make a difference there, too, the survey found.

Three most resistant groups

Encouragement from faith leaders will be especially fruitful among three of the groups most likely to include the vaccine hesitant — white evangelical Protestants, Hispanic Protestants and Black Protestants.

Encouragement from faith leaders will be especially fruitful among three of the groups most likely to include the vaccine hesitant — white evangelical Protestants, Hispanic Protestants and Black Protestants.

Among Hispanic Protestants, 42% currently are vaccine hesitant and an additional 15% are vaccine refusers. Among white evangelicals, 28% are vaccine hesitant and another 26% say they will not get vaccinated. Among Black Protestants, 32% are vaccine hesitant and 19% say they will refuse to get vaccinated.

Segments of these same groups, however, told pollsters they might change their minds if encouraged toward vaccination by their faith communities.

Among those who are hesitant to get vaccinated, 70% of Black Protestants, 66% of white evangelical Protestants, 53% of Hispanic Catholics, 43% of white Catholics, 36% of white mainline Protestants and 21% of religiously unaffiliated Americans said they would turn to religious leaders for information on vaccines at least a little.

Faith-based approaches

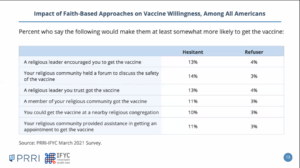

Also among the vaccine hesitant, 26% said that one or more of several specific faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get vaccinated. Even among vaccine rejecters, 6% said one or more faith-based approaches might sway them.

Those surveyed approaches include a religious leader encouraging them to take the vaccine, a religious community holding a forum to discuss the vaccine, a religious leader or other members of the community getting the vaccine, religious communities offering the vaccine at their buildings, and religious communities offering assistance for scheduling and getting to a vaccination site.

Those surveyed approaches include a religious leader encouraging them to take the vaccine, a religious community holding a forum to discuss the vaccine, a religious leader or other members of the community getting the vaccine, religious communities offering the vaccine at their buildings, and religious communities offering assistance for scheduling and getting to a vaccination site.

The survey found important differences between those who regularly attend religious services and those who claim adherence but do not regularly attend. This factor creates opposite effects among Black Protestants and white evangelical Protestants, however.

Black Protestants who do not regularly attend services are less likely than those who do attend to get vaccinated, while among white evangelicals, those who attend services are less likely than non-attenders to get vaccinated.

“Black Protestant churches are doing something to encourage vaccine adoption,” said Natalie Jackson of PRRI, noting a “very large drop-off” in vaccination rates of Black non-attenders compared to those who attend services.

“Black Protestant churches are doing something to encourage vaccine adoption.”

Nationwide, among those who attend religious services at least occasionally and are vaccine hesitant, 44% said they would be more likely to get vaccinated with one or more of the faith-based approaches, as would 14% of vaccine refusers who regularly attend religious services.

Among Black Protestants, 52% of the vaccine hesitant said they might be influenced toward vaccination by faith leaders. The same is true for 43% of white evangelical Protestants.

Who are the vaccine hesitant?

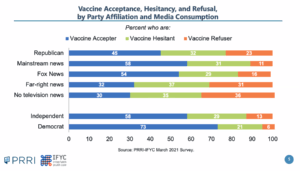

Understanding who are the vaccine hesitant is a complex picture, the researchers said, but some trends are clear. Hispanic Protestants are the largest vaccine-hesitant group; political identity and trusted news sources are indicators of vaccine acceptance; and adults under age 50 are more likely to be vaccine refusers.

The age factor could be due to access issues, as the survey was conducted in March when most adults under age 50 were not yet eligible for vaccination, Jackson explained. “It will be interesting to see how this plays out longer term.”

The age factor could be due to access issues, as the survey was conducted in March when most adults under age 50 were not yet eligible for vaccination, Jackson explained. “It will be interesting to see how this plays out longer term.”

As other surveys have shown, the new data confirmed that education levels create a stark divide among Americans and their views about vaccination. Among white Americans, those with at least a four-year college degree are 25 points more likely to be vaccine accepters. Among Black Americans, the college-degree gap is 26 points.

Political identity also was confirmed as a dividing factor. Republican voters in general are among the most vaccine resistant, with 32% being hesitant and 23% being refusers. The new data found the only thing more likely to predict being a vaccine denier than being a Republican is to be a white evangelical Protestant or to live in a rural area.

News sources and QAnon beliefs

More than political identity, however, the study found trusted news sources make a difference in vaccine acceptance. It’s not just that Republicans in general are resistant to the vaccine, but that Republicans who rely on the most far-right news sources are more resistant.

“There’s an assumption that Fox News is working to make Republicans more extreme on many dimensions. This, however, doesn’t seem to be one of them,” Jackson noted. What seems to matter instead, she said, is reliance on far-right news sources.

“There’s an assumption that Fox News is working to make Republicans more extreme on many dimensions. This, however, doesn’t seem to be one of them,” Jackson noted. What seems to matter instead, she said, is reliance on far-right news sources.

Belief in QAnon conspiracy theories also correlates with vaccine resistance and refusal, the survey found.

The survey asked respondents whether they agree with four common tenets of QAnon-related conspiracy theories, including three that have nothing to do with vaccination. The result was that 88% of America’s vaccine refusers said they believe some or all of the QAnon conspiracies, compared to 13% of the overall population who believe QAnon.

However, those who agree with QAnon conspiracy theories are among the most likely to overcome vaccine hesitancy when influenced by faith leaders. Among those who generally agree with QAnon conspiracy theories and who are vaccine hesitant, 36% said one or more of the faith-based approaches would make them at least somewhat more likely to get a vaccine.

What should be done?

The bottom line to the survey results is that “America’s religious congregations can be a powerful tool for convincing hesitant Americans to get vaccinated,” said Jones of PRRI.

Patel compared the present moment to a football game. “The long last mile to the end zone is going to be the long game, person to person, congregation to congregation,” he said. “Religious engagement, particularly in a localized way, does encourage people to take the vaccine.”

“America’s religious congregations can be a powerful tool for convincing hesitant Americans to get vaccinated.”

This may seem counterintuitive considering the declining influence of religion on American life, he noted. “For all the talk about the erosion of religion, it turns out that religious communities are strong repositories of trust. … We cannot get to herd immunity without dealing with religious identity.”

Patel offered three specific recommendations based on the new data:

- Expand faith-based vaccination sites. “It really does make a difference,” he said.

- Expand data gathering to monitor progress. “There ought to be a faith attitudes and vaccine tracker,” he suggested, to keep tabs on how faith communities are making a difference.

- Scale faith community health ambassadors. He advocated for creating ambassador programs that promote faith-based advocacy for the vaccine — “people who are paid to start conversations in diverse communities, to do the person-to-person, hand-to-hand work that is characteristic of an effective ground game.” IFYC, for example, has committed to mobilize volunteers on 100 college campuses to promote faith-based encouragement of vaccination.

The survey was conducted online March 8-30 with a sample balanced to be representative of the entire United States. It carries a margin of error of 1.5 percentage points.

Related articles:

4 in 10 Americans don’t see getting vaccinated as a way to ‘love your neighbor’

Public health officials find churches are ideal sites for COVID vaccine clinics