In 2013, Reid Trulson was researching the history of missions in the American Baptist Churches USA when he stumbled across the name of a Charlotte H. White, a previously unremembered 19th century missionary.

Then serving as executive director of ABCUSA’s International Ministries, Trulson said he knew other women involved in missions during that era had been sent as “aides” to their missionary husbands without official appointments. But that was not the case for White, a widow who was appointed in 1815 by the Baptist Board of Foreign Missions.

“The more research I did, it became clear to me that the Congregationalists were not appointing women,” Trulson explained on a recent Baptist History and Heritage Society webinar. “No other denomination or mission agency was appointing women. It gradually became clear to me that she was the first woman in all of America to be officially appointed. And I thought that was rather significant.”

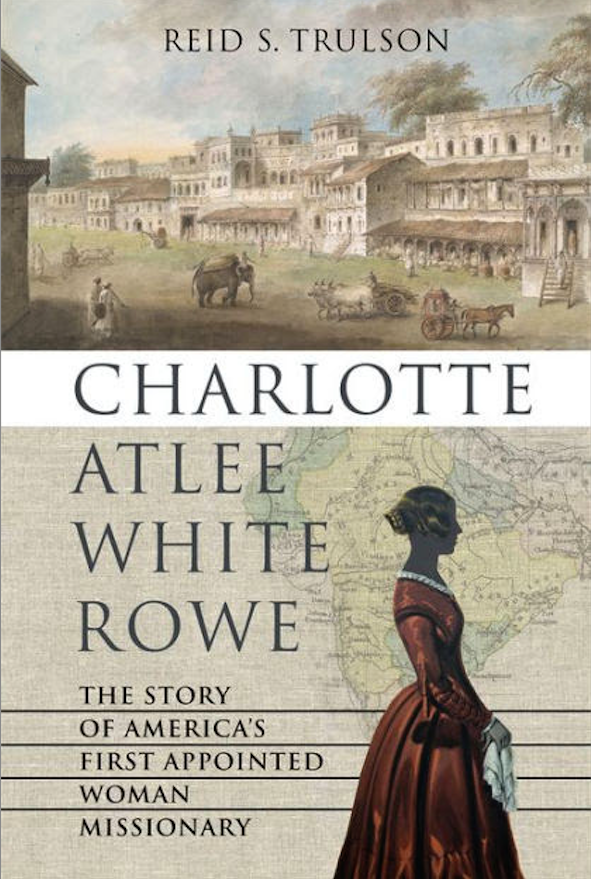

Significant enough for Trulson to write Charlotte Atlee White Rowe: The Story of America’s First Appointed Woman Missionary. The 2021 book was the focus of the history society’s most recent “Making Baptist History Public History” online discussion.

Significant enough for Trulson to write Charlotte Atlee White Rowe: The Story of America’s First Appointed Woman Missionary. The 2021 book was the focus of the history society’s most recent “Making Baptist History Public History” online discussion.

“To me, it’s a matter of justice and I feel it’s appropriate for us to honor her by letting people know about her life and about her ministry,” he said.

The way she overcame obstacles on the way to appointment and during her decade-long international missionary service may be a model for those facing gender bias in ministry in the 21st century, Trulson said. “To tell the story of this woman and how she persevered and achieved so much, I felt was important modeling for men and women today.”

One of White’s significant accomplishments was obtaining an appointment from the body that eventually would become the American Baptist Foreign Mission Society and International Ministries.

Her first barrier was simple: This hadn’t been done before.

“Adoniram and Ann Judson were the first Baptist missionaries to Burma, and I had always assumed that they were both appointed,” Trulson explained. “But the surprise was to discover that only Adoniram was appointed and Ann was not. And then, as I did a little more looking through the archives, I discovered that none of the women who were being sent were appointed. So, Adoniram was appointed in 1814 and the very next year Charlotte H. White was appointed as a missionary to go to Burma to work with the Judsons. And I was astounded.”

But her appointment by the all-male board didn’t go smoothly, the author explained. “All the actions of the board up to that point had been unanimous. But not her appointment. There were several people who voted against it.”

One of those opponents was Henry Holcomb, a Philadelphia pastor and a believer in the then-popular “separate spheres” view of differentiating the roles of men and women.

“It was the concept that there was a public sphere and a private, or a domestic, sphere,” Trulson said. “The public sphere was intended by God to be the sphere of activity for men. So that was business. It was politics. It was economics. It was anything that had a public face. The woman’s sphere was considered to be the domestic sphere that meant home, family, children, church — as long as you had the right role in church.”

“To appoint a woman to this public-sphere role was usurping the authority over the men.”

Holcomb also presented “his view of the inferiority in some respects of the woman to the man. He says it’s the man who is the image and glory of God, not the woman, and to appoint a woman to this public-sphere role was usurping the authority over the men.”

Yet White, then a member of Sampson Street Baptist Church in Philadelphia and a co-founder of its Woman’s Missionary Society, overcame the challenge on the grounds that the mission board’s constitution did not define the word “missionary” as either male or female, or even ordained or not ordained.

However, the board refused to fund her travel and work. “So, she offered part of her estate to the Baptist board on the condition that they would use those funds to pay for her expenses,” Trulson reported. “In other words, the first woman in all of America to be officially appointed as an international, cross-cultural missionary ended up funding her own work. And she would fund her own work for the entire decade that she would serve.”

Reid Trulson

White’s calling to missions was preceded by childhood in her native city of Lancaster, Pa., where her mother died when she was 8 and her father died three years later, prompting a move to Massachusetts to live with family. She eventually married and had a son, but the boy died in infancy and her husband died a year later, leading to a relocation within the state.

“And there she met the Baptists,” Trulson said. “Charlotte is baptized and becomes a member of the Baptist church in Haverhill.” Evidence suggests she previously attended Episcopal and Congregational churches.

Her new congregation had a robust missions society and was directly involved in aiding the work of missionary William Carey in India. “It’s quite likely that a lot of this influenced and was part of Charlotte’s call,” Trulson said. Records show “she experienced a call to missions at the time that she became a believer.”

But White’s goal of working with the Judsons changed when she met Joshua Rowe, an English Baptist missionary in India, while enroute to Burma. They married and the couple had three children and she remained with him in Digah, India, until his death in 1823.

She was busy all that time living out her calling, Trulson said. “Charlotte was an educator. She supervised several schools and started schools for girls because most that existed were just for boys. She had to buck opposition from the East India Company, which didn’t believe Indian children should be educated” from fear it “could imperil colonial administration and their profits.”

White became fluent in Hindi to ensure the schools she led were in the language of her students and their families.

White became fluent in Hindi to ensure the schools she led were in the language of her students and their families.

“The Little Baptist congregation on the mission station was in Hindi,” Trulson said. “So, on Sunday mornings, Joshua goes to the cantonment or elsewhere to preach in English and Charlotte was engaged in leading services in Hindi.”

But Rowe’s death ended support for the mission by the Baptist Missionary Society office in London, which also declined White’s request for a missionary appointment and funds to continue her work. “The leaders of the BMS in London felt it would be too controversial to appoint a woman, and so she knew that there was no hope for her return.”

Back in the U.S., White operated boarding schools, academies and even a seminary for women, Trulson said. But she also would suffer the death of her remaining children before her own death on Christmas Day 1863.

“She is owning the title. ‘I am a missionary,’”

The courage and power of calling White exemplified during her life are displayed in a diary she began in 1815, Trulson noted. In it, she announces its purpose is to document her “missionary career.”

“That phrase might not strike us as being particularly important, but in the setting of the time, it’s revolutionary. First of all, she is owning the title. ‘I am a missionary,’” he said.

“Ann Judson, Harriet Newell and other women who had been sent … were considered to be volunteers who assisted their husbands. Sometimes, they were referred to as assistant missionaries, but they never had the official status of a missionary themselves,” Trulson explained. “So, the word ‘missionary’ is important. The second word is equally important: she’s speaking of her missionary ‘career.’ This is a time in which no one would speak of a woman having a career beyond the career of being a wife and a mother and a housekeeper.”

Related articles:

The year of being threatened by smart women | Analysis by Mark Wingfield

It’s time to remember the first American woman appointed an international missionary — whose name you’ve probably never heard | Opinion by Reid Trulson

GAs Gone Bad: Baptist women you should be reading | Opinion by Susan Shaw