New data from PRRI’s Census of American Religion show continued decline of white evangelicals as a proportion of the American population.

I prefaced my 2016 book, The End of White Christian America, with an “Obituary for White Christian America.” It read, in part:

After a long life spanning nearly 240 years, White Christian America — a prominent cultural force in the nation’s history — has died. WCA first began to exhibit troubling symptoms in the 1960s when white mainline Protestant denominations began to shrink but showed signs of rallying with the rise of the Christian Right in the 1980s. Following the 2004 presidential election, however, it became clear that WCA’s powers were failing.

Although examiners have not been able to pinpoint the exact time of death, the best evidence suggests that WCA finally succumbed in the latter part of the first decade of the 21st century. The cause of death was determined to be a combination of environmental and internal factors — complications stemming from major demographic changes in the country, along with religious disaffiliation as many of its younger members began to doubt WCA’s continued relevance in a shifting cultural environment.

Robert P. Jones (Photo by Noah Willman)

The End of White Christian America was published in July 2016, just as Donald Trump was securing the Republican nomination for president and the Make America Great Again worldview was supplanting policy considerations within the GOP (indeed, by the end of Trump’s presidency, the party officially abandoned any attempt to adopt an official policy platform). The data I had available at the time identified a watershed event that was driving this desperate movement: The U.S. had become — for the first time in our history — a country that was, demographically speaking, no longer a majority white Christian country.

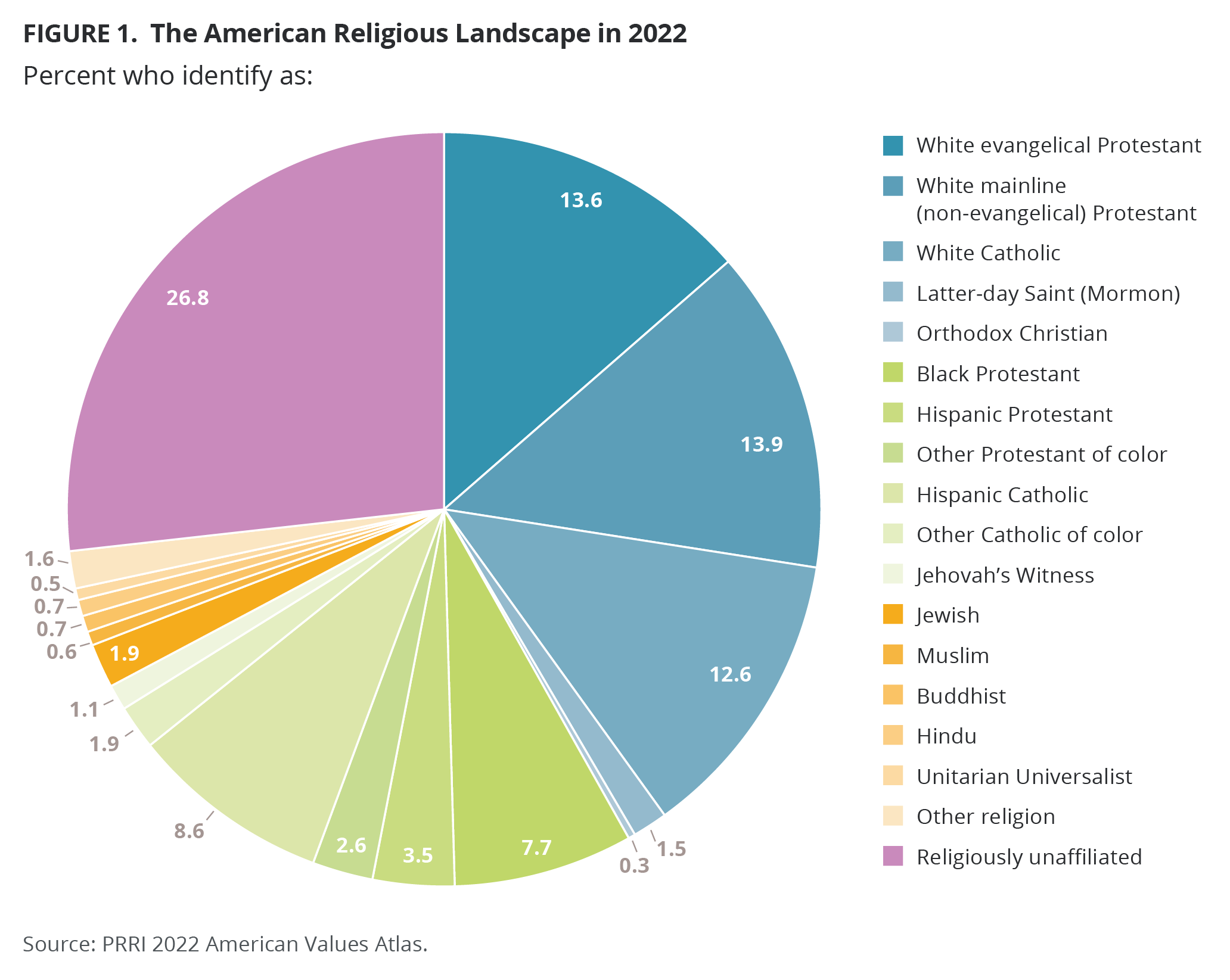

The newly-released 2022 supplement to the PRRI Census of American Religion — based on more than 40,000 interviews conducted last year — confirms that the decline of white Christians (Americans who identify as white, non-Hispanic and Christian of any kind) as a proportion of the population continues unabated.

As recently as 2008, when our first Black president was elected, the U.S. was a majority (54%) white Christian country. As I documented in The End of White Christian America, by 2014, that proportion had dropped to 47%. Today, the 2022 Census of American Religion shows that figure has dropped further to 42%.

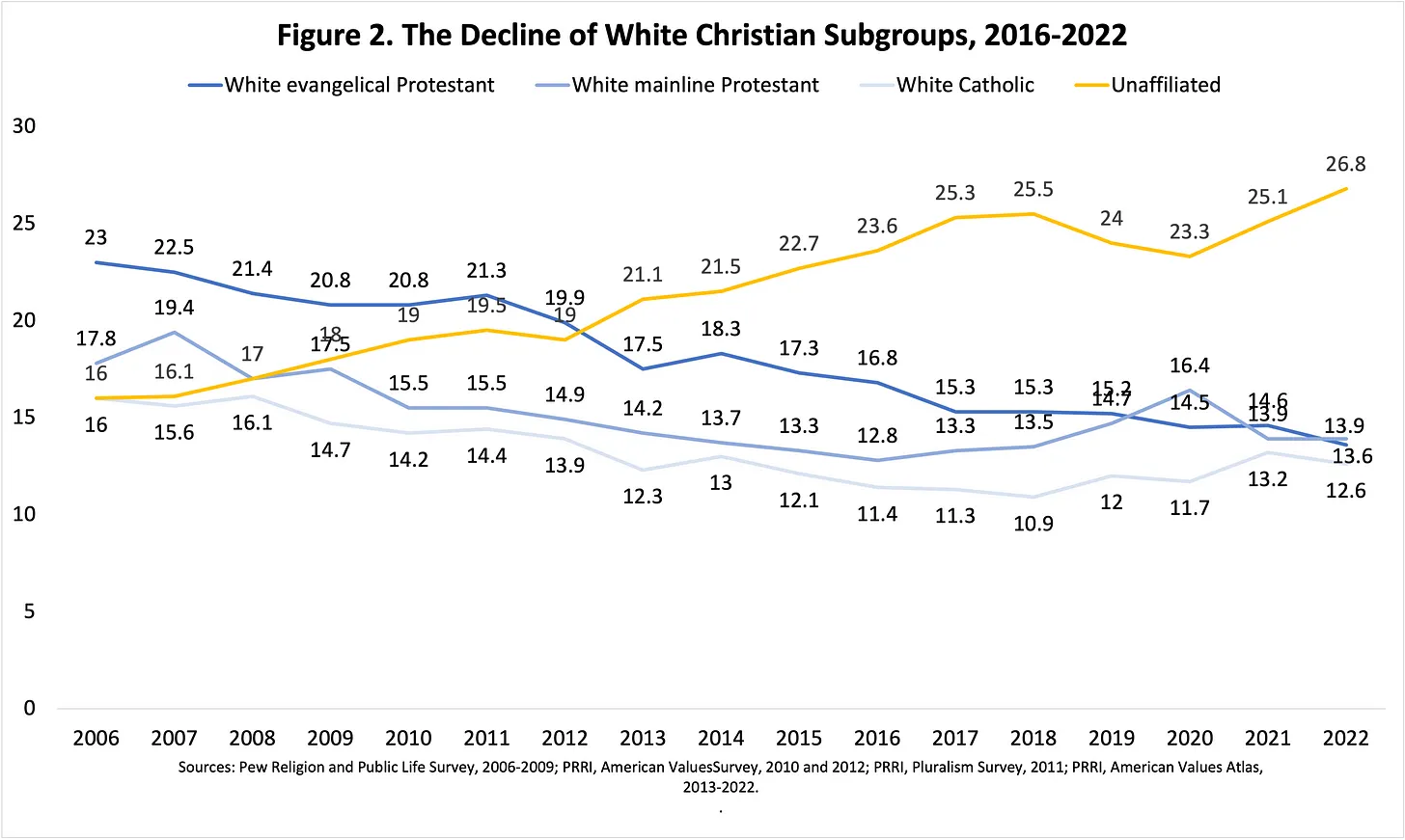

As figure 2 below demonstrates, all white Christian subgroups — white evangelical Protestant, white non-evangelical/mainline Protestant, and white Catholic — have declined across the last two decades. Notably, in the last 10 years, white evangelical Protestants have experienced the steepest decline. As recently as 2006, white evangelical Protestants comprised nearly one-quarter of Americans (23%). By the time of Trump’s rise to power, their numbers had dipped to 16.8%. Today, white evangelical Protestants comprise only 13.6% of Americans. As a result of this precipitous decline, white evangelical Protestants are now roughly the same size as white non-evangelical/mainline Protestants, a group that experienced its own decline decades early, but has now generally stabilized.

As the fine print on retirement investment statements remind us, past trends are no guarantee of future performance. But there is no evidence suggesting any immanent reversal of these trends. The median age of all white Christian subgroups — 54 for both white evangelical and non-evangelical/mainline Protestants, 58 for white Catholics — is considerably higher than the median age of all Americans (48), an indication of the exodus of younger adults from these congregations. By contrast, the median ages of Christians of color, non-Christian religious groups, and the religiously unaffiliated are all more consistent with or even below the median age of the country.

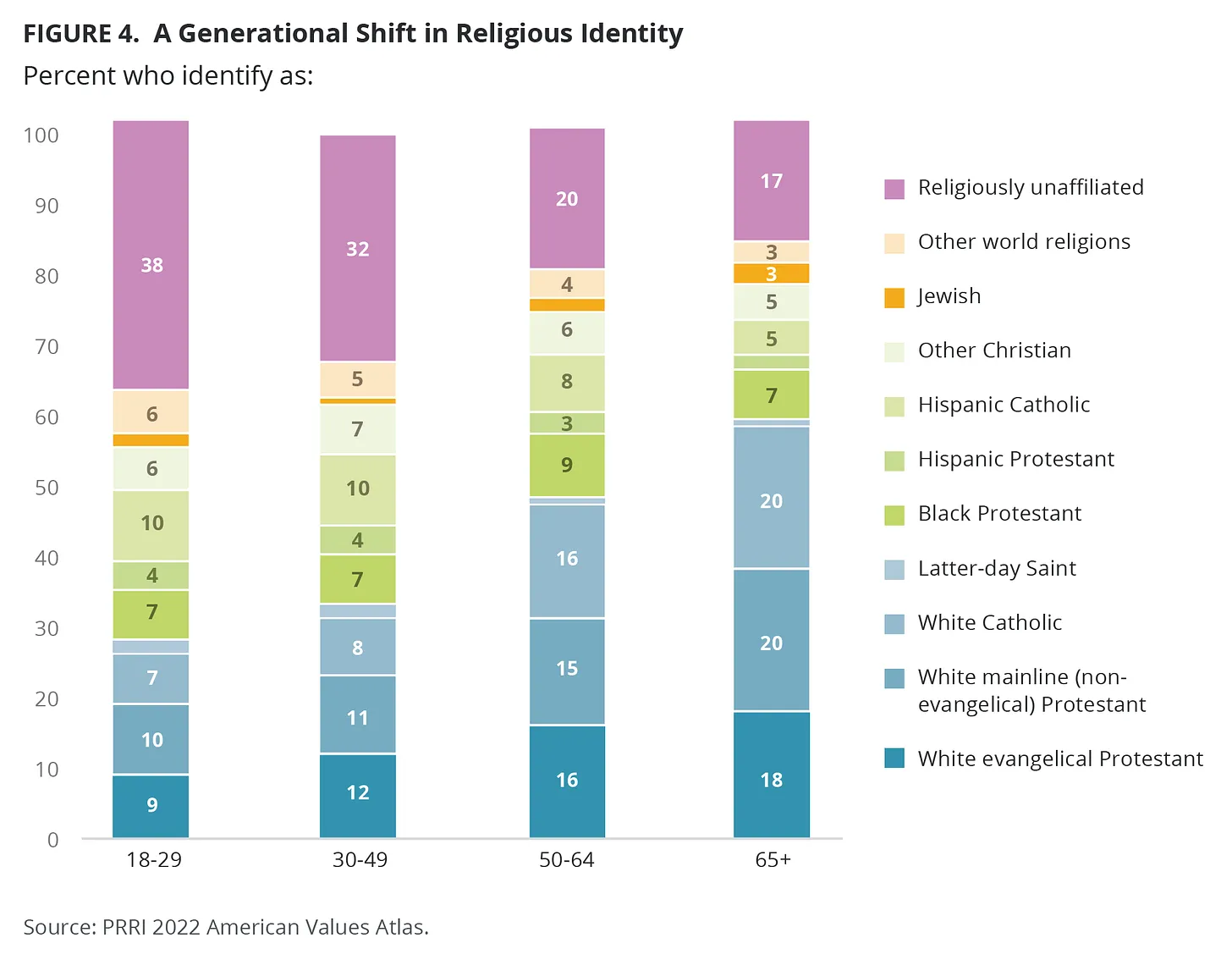

An examination of religious affiliation by age cohorts demonstrates a marked, linear decline of the share of white Christians in each successive younger group. Comparing the oldest (ages 65-plus) to the youngest (ages 18 to 29) group of American adults reveals white Christian subgroups each have lost approximately half their market share just across the generations who are alive today. For example, 18% of seniors, compared to only 9% of young adults, identify as white evangelical Protestant.

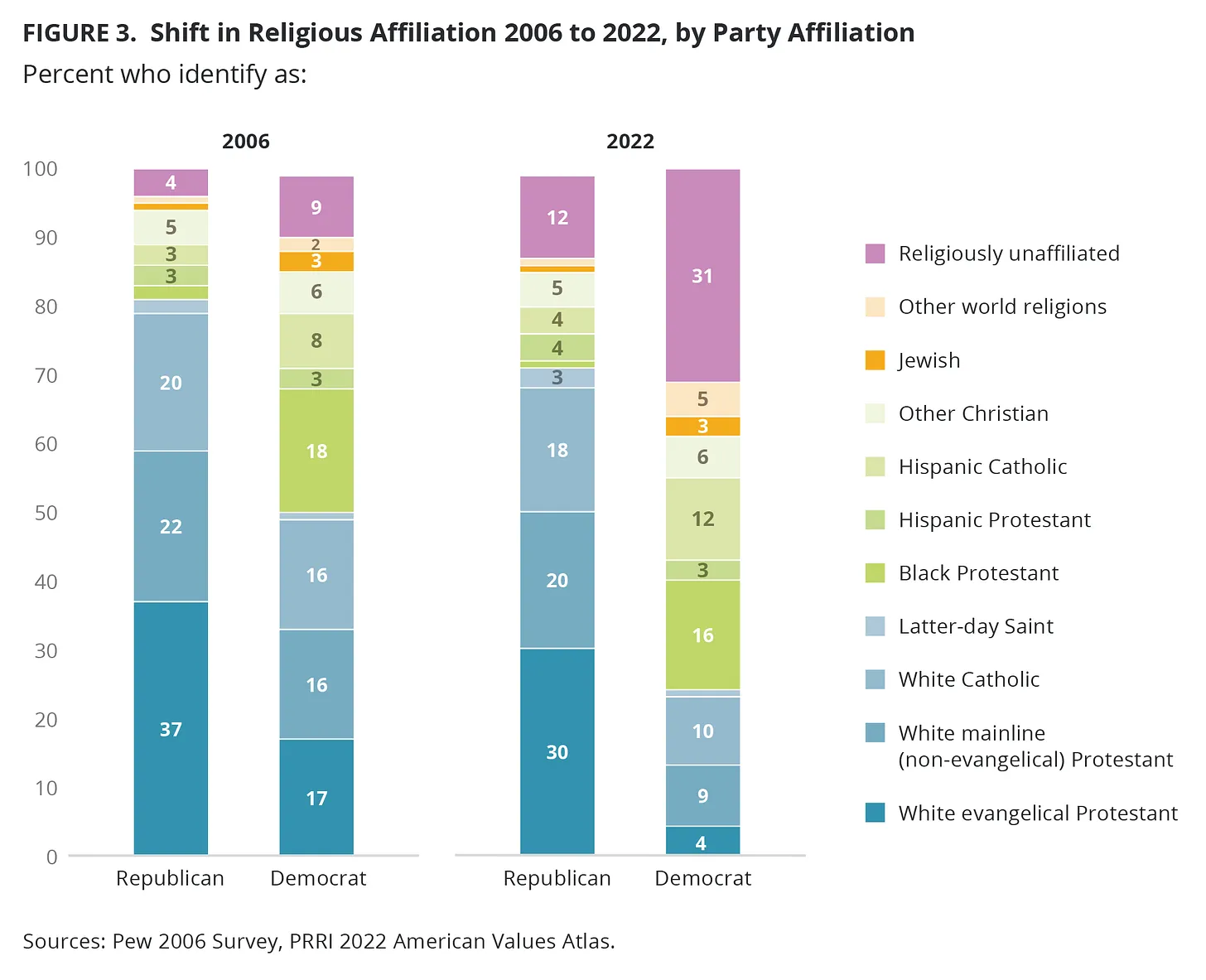

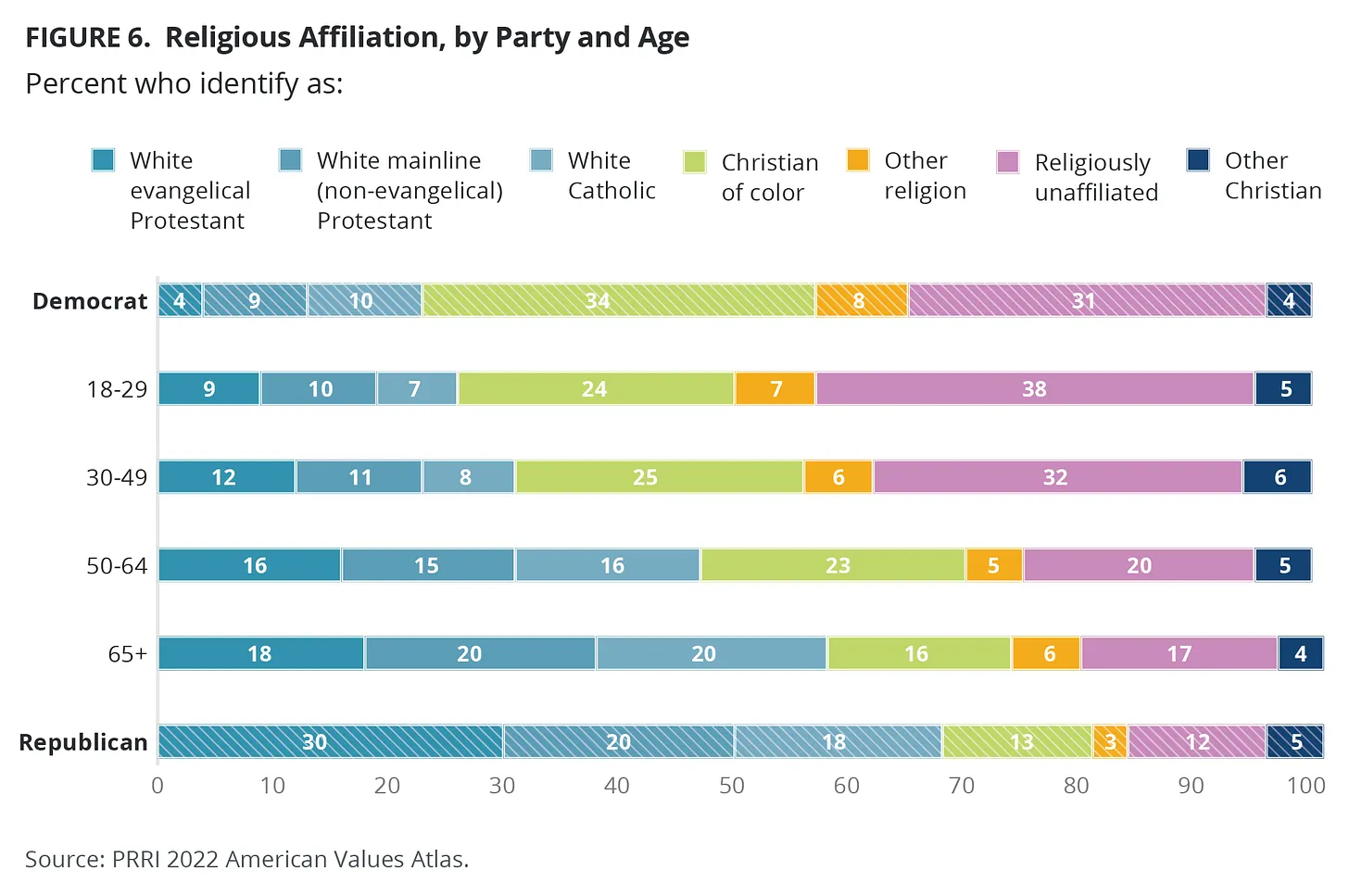

As the numbers of white Christians have dropped, their presence in our two political parties also has shifted. Two decades ago, white Christians comprised about eight in 10 Republicans, compared to about half of Democrats, a gap of about 30 percentage points. As their numbers have declined, this gap has increased to about 45 percentage points, with white Christians continuing to account for about seven in 10 Republicans but only about one quarter of Democrats.

If we overlay the current ethno-religious composition of our two political parties onto the generational cohort chart, we see a stunning result. In terms of its racial and religious composition, the Democratic Party looks like 20-year-old America, while the Republican Party looks like 80-year-old America.

In The End of White Christian America, I summarized the political polarization this cultural and demographic shockwave had generated: “The two divergent and competing narratives — one looking wistfully back to midcentury heartland America and one looking hopefully forward to a multicultural America — cut to the heart of the massive cultural divide facing the country today.” Trump’s ascendancy, leading ultimately to a violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, only heightened this fundamental divide over two incompatible visions of America.

While I held out some possibility in 2016 that white evangelicals and other conservative white Christians might accept their new place alongside others in an increasingly pluralistic America, their steadfast allegiance to Trump’s MAGA vision — actually increasing their support for him between 2016 and 2020 — and their unwillingness to denounce either Trump’s Big Lie that the election was stolen or the violence on January 6 have dashed those thin hopes.

Back in 2016, here’s how I described the likely consequences if white conservative Christians dug in:

(White Christian Americans’) greatest temptation will be to wield what remaining political power they have as a desperate corrective for their waning cultural influence. If this happens, we may be in for another decade of closing skirmishes in the culture wars, but white evangelical Protestants will mortgage their future in a fight to resurrect the past.

But as alluring as turning back the clock may seem to White Christian America’s loyalists, efforts to resurrect the dead are futile at best — and at worst, disrespectful to its memory. Like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, resurrection by human power rather than divine spirit always produces a monstrosity.

The continued demographic decline makes it clear the MAGA goal of reestablishing their vision of a white Christian America can’t be realized by democratic means. But as I explained in my most recent posts, I’m deeply concerned that the embrace of Christian nationalism by nearly two-thirds of white evangelicals and a majority of the Republican Party will spawn more theological monstrosities justifying anti-democratic schemes to achieve this end.

Robert P. Jones is CEO and founder of PRRI and the author of White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity, which won a 2021 American Book Award.

This column originally appeared on Robert P. Jones’s substack #WhiteTooLong.