Anyone who assumed that a growing number of Americans would abandon a politicized evangelicalism over its support for Donald Trump appears to have been wrong, new research shows.

On the contrary, a new analysis reveals no significant abandonment of evangelicalism by white Americans during the four years of the Trump presidency, Pew Research Center reported. In fact, increased identification with the evangelical label by white Trump supporters offset the losses of other non-white Americans leaving behind the evangelical label.

“There was no mass departure of white Americans from evangelical Protestantism between 2016 and 2020,” Pew said in a Sept. 15 report about its American Trends Panel, which focuses on the relationship between the former president and evangelicals. The panel consists of data collected immediately after the 2016 election and another after the 2020 election.

“In fact, there is solid evidence that white Americans who viewed Trump favorably and did not identify as evangelicals in 2016 were much more likely than white Trump skeptics to begin identifying as born-again or evangelical Protestants by 2020,” Pew reported.

“In fact, there is solid evidence that white Americans who viewed Trump favorably and did not identify as evangelicals in 2016 were much more likely than white Trump skeptics to begin identifying as born-again or evangelical Protestants by 2020,” Pew reported.

Some observers had predicted that because of Trump’s track record as a liar, womanizer and bully — traits previously considered antithetical to the life of virtue espoused by evangelicals — more evangelicals would pull away from him. Instead, the opposite happened among white evangelical voters.

“The data also show that Trump’s electoral performance among white evangelicals was even stronger in 2020 than in 2016, partially due to increased support among white voters who described themselves as evangelicals throughout this period,” Pew reported.

Pew also tracked a 4% uptick in evangelical identification between the two election cycles, with 25% of white adults claiming the status in 2016 and 29% doing so in 2020.

Losses offset by gains

“Of course, this doesn’t mean that no one stopped identifying with evangelicalism between 2016 and 2020,” Pew added. “The survey shows that among white respondents who participated in both surveys, 2% identified as born-again/evangelical Protestants in 2016 and no longer did so by 2020. However, the 2% of white adults who stopped identifying as evangelicals during Trump’s term were more than offset by the 6% of white adults who began calling themselves born-again/evangelical Protestants” in the same period.

The most defections of any label were among white Protestants who did not identify as evangelicals in 2016, Pew said. “Overall, 6% of white adults described themselves as non-evangelical Protestants in 2016 but not in 2020, while 3% started identifying as such during the Trump administration.”

White Americans with “warm views toward Trump” were far more likely than those with less favorable attitudes toward the 45th president to adopt the evangelical moniker during his term, Pew said, “perhaps reflecting the strong association between Trump’s political movement and the evangelical religious label.”

Nor was there any clear evidence that anti-Trump white evangelicals were more likely than his proponents to leave the fold. In fact, the “vast majority” of white adults who claimed evangelical Protestant status in 2016 still did so four years later.

The research also revealed a sizeable increase in evangelical backing for Trump between the two elections.

“Among white respondents (both voters and nonvoters) who identified as evangelical Protestants in 2016 and expressed at least some ambivalence about Trump, 88% still identified as evangelicals in 2020, while 12% no longer did so. Among consistent Trump supporters, 93% still identified as evangelicals in 2020, while 7% no longer did. Though the 12% defection rate among Trump skeptics is nominally higher than the 7% defection rate among Trump supporters, the difference is not statistically significant.”

The research also revealed a sizeable increase in evangelical backing for Trump between the two elections.

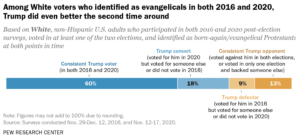

“Trump garnered even more support in 2020 than in 2016 among white voters who identified as evangelical Protestants in both years and voted in at least one of the two elections,” Pew said. “Six in 10 in this group were consistent Trump supporters who cast ballots for him in both 2016 and 2020, and an additional 18% were Trump converts — they backed him in 2020 after voting for another candidate or not voting at all in the 2016 general election. In total, 78% of white voters who identified as evangelicals at both points in time voted for Trump in 2020.”

In comparison, 9% of white evangelical voters were defectors who supported a different candidate last year after voting for Trump in 2016, with the remainder not voting for him in either election.

“Trump’s improved performance among this group is one key reason that his overall vote share among white evangelical voters — including those who’d been evangelical all along and those who began identifying as evangelical between 2016 and 2020 — ticked up from 77% in 2016 to 84% in 2020.”

A different story with non-white evangelicals

Data collected about non-white evangelicals was less granular, Pew said. “The surveys did not include enough interviews with Black, Hispanic and other non-white Americans to permit analyzing them separately, or to discern whether Trump opponents were more likely than Trump supporters to drop the evangelical label.”

Even so, the research found that the share of non-whites who have ceased identifying as evangelical or born-again “in recent years is offset by the share who adopted it,” Pew added.

“In the 2020 survey, for example, just 30% of non-white voters who identify as born-again or evangelical Protestants … reported casting a ballot for Trump.”

“Among non-white respondents who participated in both the 2016 and 2020 surveys, 26% identified as born-again/evangelical Protestants in 2016, and 25% identified this way in 2020. Of course, some did drop the born-again/evangelical label during Trump’s term (7% of all non-white respondents), but they were offset by an equal share (7%) who adopted the born-again/evangelical label during the same period.”

But there were bigger differences in voting habits among this population. “In the 2020 survey, for example, just 30% of non-white voters who identify as born-again or evangelical Protestants (including just 12% of Black evangelical voters) reported casting a ballot for Trump.”

What does this mean?

The new polling data prompted a new round of commentary by scholars who study evangelicalism and politics and previously have tried to point out the deep connections between Trumpism and white evangelicals.

Among those is Anthea Butler, professor of religious studies and Africana studies at the University of Pennsylvania and author of White Evangelical Racism: The Politics of Morality in America.

In a c0lumn she wrote for MSNBC, Butler said the term “evangelical” “doesn’t mean born-again anymore; it means Republican.”

She added: “When it comes down to it, ‘evangelical’ is more a political label than a religious one. People who embrace the label use it to signal that they’re against immigration, science and abortion and to signal a belief that discussions of racism in America are antithetical to their idea of America.”

“‘Evangelical’ is more a political label than a religious one.”

As a result, evangelicalism today “is not a religious group exclusively, but a majority white religious group linked strongly to Trump, the Republican party and particular ideas about race, gender, morality and America,” Butler wrote.

Historian Thomas Kidd of Baylor University sees a more ominous warning in the new Pew data. He told Christianity Today that the possibility that Americans began calling themselves “evangelical” simply because they backed Trump “should be of concern to all pastors and committed churchgoers.”

He added: “There are good reasons for churches to continue to describe themselves as ‘evangelical,’ if by that term they are referencing their historic commitment to the Bible’s authority, the necessity of spiritual conversion, and the felt presence of God in daily life. But pastors in particular should realize that the meaning they attach to ‘evangelical’ may not be the same as that of some in their congregation. I suspect most pastors would not want to inadvertently signal to their congregations that they are effectively branch offices of Donald Trump’s GOP, simply by making undefined use of the term ‘evangelical.’”

Christianity Today quoted another scholar who has coined a term to describe the phenomenon of assuming the label of “evangelical” as an indication of supporting Trump. Mark Caleb Smith, director of the Center for Political Studies at Cedarville University, noted: “If the Pew study holds up, and is confirmed by other data sources, it presents the challenge in a new light. Is it possible that people not within the religious tradition of evangelicalism are only ‘political evangelicals’? Does this reflect poorly on us?”

Related articles:

Trump candidacy will test evangelical voters, says SBC leader

‘Evangelical elite’ just doesn’t get it, claims pastor and Trump supporter

The Trump Card: How white evangelicals are being played | Opinion by Joel Bowman Sr.