Editor’s note: Laine Scales and Melody Maxwell have written a new book about the history of the Carver School of Church Social Work at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, its 1997 closing and its legacy carried forward at Baylor University. What follows is an excerpt of the Epilogue to their book.

Kristen Tekell Boyd

In November 2017, Kristen Tekell Boyd stands in the pulpit of Truett Seminary’s chapel in Waco, Texas, and preaches, taking Ezekiel chapter 37 as her text. As she describes the valley with the prophet Ezekiel coming upon the dry bones, she reads a key question from the Scripture: “Can these bones live?”

This question might have been asked 20 years before when Carver School of Church Social Work closed in 1997, an event that seemed like a death to many of its alumni.

She continues, “God created (these bones) from the dust, and God is the only one who can breathe life into them once again.” After recalling several stories of loss and death, Boyd assures her listeners that God is with us. She closes her sermon with a hopeful directive: “Let us be a people that rise and bear witness; rise and remember!”

Boyd is a recent graduate of Baylor University’s dual degree program, awarding two integrated master’s degrees: a master of social work from the Diana R. Garland School of Social Work and a master of divinity from George W. Truett Seminary. Although only a young child during the events of Carver School’s final closing in 1997, Boyd is a “granddaughter” of the WMU Training School who can trace her educational lineage back to 1904 and the first four women quietly listening in on lectures halfway across the country at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky.

Goodwill Center, operated by the WMU Training School, ca. 1915. (Photo from Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archive)

This connection may not seem apparent at first because Boyd never has been to Louisville. After the school operated for 90 years in Louisville, however, the Carver School family’s figurative “heads of household” moved West in the late 1990s. The two former deans of Carver School of Church Social Work, Anne Davis and Diana Garland, relocated to Waco. Several alumni and supporters followed. This group modified the Carver School dream and, at Baylor University, built a curriculum of social work and theological education to prepare social work ministers serving congregations and faith-based agencies. This generation of graduates would inherit the Carver School legacy.

Although living in a different time and place, Boyd has much in common with her training school grandmothers in Louisville 100 years before her. Like them, she studied diligently to prepare herself intellectually, spiritually and practically to respond to God’s calling, dividing her class time between two buildings on an urban campus. Her intellectual and spiritual task was to integrate social work skills with biblical and historical traditions gleaned from seminary classes.

Boyd is a “granddaughter” of the WMU Training School who can trace her educational lineage back to 1904.

She also was exposed to Baptist tradition, including opportunities to meet important Baptists visiting her school. She did field work in agencies around the city, just as her training school ancestors had done, and she even volunteered in a modern-day settlement house, founded by a Carver School alumna.

As graduation approached, Boyd prayed with her classmates to hear God’s calling about next steps, just as Jewell Legett prayed with Jane Lide in the halls of the training school in 1909. Like many of her training school grandmothers, Boyd met and fell in love with a seminary student; the two graduates married and began working together in the same Baptist institution.

Boyd’s relationship to an earlier generation of training school women may be one of “vocational kinship,” Rosemary Keller’s term for religious women’s “shared identity growing out of a commitment to mutual purpose and values.” Her opportunities, however, are much more expansive than those of Baptist women in the early 20th century.

The congregation that gathered for her sermon in November 2017 was made up of both men and women. Unlike Annie Armstrong’s generation, Boyd has not been socialized to believe she cannot speak before a “mixed” audience. She stands firmly behind the pulpit and claims all its authority; she does not have to step to the side of the “sacred desk” as student Carrie Littlejohn was taught to do in the training school chapel.

After the worship service, Boyd is greeted by Kathy Hillman, a WMU leader who volunteered alongside Boyd’s mother and has encouraged Boyd in her calling from childhood. The hug between the two women signals that the WMU network of support is still alive and well. Boyd also is congratulated by two role models, women pastors who graduated just a few years before her, and lead Baptist churches in Waco.

Although the pastoral role was outlawed for graduates of the training school, it is possible for women of Boyd’s generation, at least in moderate and progressive Baptist churches. These opportunities are available because the SBC’s deep fractures brought together moderate Baptists at new seminaries to support women’s pursuit of any roles to which they are called, including preaching.

Kristen Tekell Boyd’s ministry serves as an encouraging epilogue to our story. Her life and calling braid together the three thematic strands of this book: shifts in education and ministry opportunities considered appropriate for Baptist women, views of social ministry among Baptists, and the place of Baptist social workers within a profession that distanced itself from religion throughout the second half of the 20th century. Other Baptist schools have opened master of social work programs in the last two decades, such as Samford University in Alabama and Campbellsville University in Kentucky, which purchased the Carver School name shortly after the school was closed.

“Could Jesus teach social work at Southern Seminary?” editorial by Marv Knox in the Kentucky Western Recorder after Diana Garland was fired as dean there.

As we write this epilogue in 2017, we acknowledge the 20th anniversary of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary’s closing of Carver School in 1997, and we find that two decades of distance has allowed us time and space to gather stories, reflect and consider the effects Carver School had on Baptist women, on social ministry and on the larger social work profession.

For the past 20 years, we both have studied, lived, worked and taught in Baptist agencies and schools. Rather than speaking as distant researchers, we add to the documented history our own voices, expressing personal perceptions of the events of the past 20 years. Melody has been most closely associated with WMU and Baptist theological education. Laine has been involved with the attempt to resurrect the Carver dream at Baylor University through the Diana R. Garland School of Social Work.

Like survivors of any earthquake that destroys a house, we have sifted through the rubble to find signs of hope. As we have participated in these events of the past 20 years we also have observed as researchers looking for broader connections and insights into American religion, particularly related to women.

While there are many similarities between Kristen Boyd’s experience and that of her training school grandmothers, profound changes in Baptist life and broader culture have created differences in the roles considered appropriate for Baptist women.

“Like survivors of any earthquake that destroys a house, we have sifted through the rubble to find signs of hope.”

While the training school and Carver School were backed by a powerful and united Southern Baptist Convention along with its hard-working auxiliary, WMU, Boyd and other women students who want to be pastors are no longer welcome in SBC seminaries. Southern Seminary president R. Albert Mohler played an important role in the SBC’s 2000 revision of its Baptist Faith and Message document. The statement addresses gender roles, including a controversial statement on the family that requires a wife to “submit herself graciously to the servant leadership of her husband … to respect her husband and to serve as his helper in managing the household and nurturing the next generation.”

It also includes prohibition of women as pastors. Since faculty of all SBC seminaries must agree to teach in accordance with the statement, women students are guided toward courses and vocational choices considered appropriate for their gender, similar to when the WMU Training School was established a century prior.

The gender controversies leading up to the 2000 Baptist Faith and Message further separated Baptists. However, the SBC’s exclusion of women from particular types of ministry roles spawned new seminaries for moderate Baptists that included women called to pastoral ministry and to theological study. In fact, Boyd’s Truett Seminary was established partly in response to the SBC’s exclusion of women, graduating its first class in 1997, just as Carver School of Church Social Work was closing its doors.

By 2002, the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship was supporting 11 seminaries and divinity schools, with seven of those enrolling over 40% women. As some women earned doctoral degrees in moderate Baptist schools, a new generation of women seminary professors and theological scholars emerged.

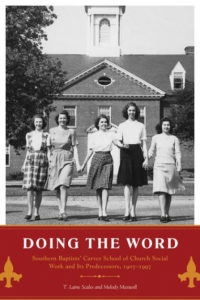

From T. Laine Scales and Melody Maxwell, Doing the Word: Southern Baptists’ Carver School of Church Social Work and Its Predecessors, 1907-1997. Copyright © 2019 by The University of Tennessee Press. Reprinted by permission.

From T. Laine Scales and Melody Maxwell, Doing the Word: Southern Baptists’ Carver School of Church Social Work and Its Predecessors, 1907-1997. Copyright © 2019 by The University of Tennessee Press. Reprinted by permission.