Across the decades, residents of “tornado alley” — the expansive swath of central North America visited by twisters every year — have heard myriad stories of inexplicable storm damage.

A single piece of straw driven through a tree trunk is an oldie but a goodie. Same for a tornado hopscotching down a street, decimating some homes and leaving neighboring houses untouched. And don’t forget tales of all kinds of items, from automobiles to teacups, carried away but placed undamaged out in a field or up in a tree.

Now, researchers have added a new, more far-reaching, illustration of quirky twister tolls: The spinning storms often inflict racial inequity on the counties they terrorize.

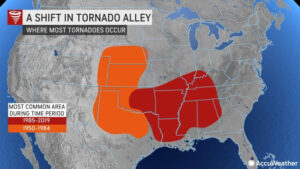

Source: Accuweather

Tornadoes are more likely to destroy property in U.S. counties with relatively more Black residents than other locales, a team of researchers discovered. Compounding the damage, tornadoes often expand the breadth of racial segregation, they learned.

The Journal of Economic Studies published the work, “Tornadoes, Poverty and Race in the USA: A Five-Decade Analysis” late last year. Researchers Russ Kashian, an economics professor at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, Tracy Buchman, an assistant professor of occupational and environmental safety at UW-Whitewater, and Robert Drago of Precision Numerics produced the study.

“In counties where tornadoes hit, … the overall proportion of Black people and the proportion of people living in poverty are both slightly higher, while median income and the proportion of people with at least a bachelor’s degree are lower,” reporter Clark Merrefield noted in The Journalist’s Resource, which distributed the information.

Although reasons for this twist of fate went unreported, the locations of the preponderance of U.S. tornadoes occur in largely rural regions, where per capita income is lower than urban and coastal regions. Also, a significant share of tornados inflicts the South, where the percentage of Black residents is higher than other parts of the country.

Beyond the propensity for tornadoes to strike Black and lower-income counties, tornadoes leave racial segregation in their wake, the researchers discovered. They cited two influences:

- Abandonment occurs when homeowners decide not to repair or rebuild their damaged houses and simply move elsewhere. White residents disproportionately possess the resources to pack up and move, the researchers reported. This leaves a higher percentage of African Americans living in those now-poorer communities.

- Displacement occurs when storm victims have access to resources — think insurance — that enable them to rebuild. Lower-income residents, who often are disproportionately Black, tend to be renters with no control over capacity to rebuild, and they find no option but to move away.

Consequently, while abandonment leaves a higher percentage of Black residents in newly poorer communities, displacement drives a higher share of Black residents from rebuilt, newly whiter and now higher-income neighborhoods.

“Abandonment is more likely in heavily populated areas, with displacement more common in rural areas,” Merrefield reported. “Counties where people were largely displaced had an average population of 38,523. Counties where people largely abandoned their homes had an average population of 286,448.”

“People with the means either do well because they’ve been able to mitigate and recover, or they leave,” Buchman told The Journalist’s Resource. “People without means end up backfilling because stuff is expensive now (in a devastated area), or they didn’t do well, and they’re still living in an area that’s vulnerable to multiple strikes of tornado and the damage that goes with it.”

Also, while storms in wealthy areas are more expensive, victims in poor areas are more likely to suffer, the researchers discovered. For example, a driver with insurance can replace an expensive car, but someone with an old car and minimal insurance may lose their only mode of transportation.

“The wealthy have more to lose (but) … the vulnerable are more likely to experience losses.”

“The wealthy have more to lose,” Kashian conceded, but “the vulnerable are more likely to experience losses.”

The researchers examined economic damages from 11,000 tornadoes that struck across five decades, beginning in the 1970s. Even accounting for inflation, storms are getting more expensive, they found. Each tornado measuring at least EF2 — wind speeds of 111 to 135 miles per hour — inflicted an inflation-adjusted cost of $131,976 in the 1970s, which dipped to $49,492 in the 1990s and then soared to $666,668 in the 2010s.

While weather patterns are not likely to change, responses to them could mitigate the problem.

The U.S. government can do better to help low-income tornado victims recover from disaster, Kashian suggested, noting the Federal Emergency Management Agency — FEMA — could distribute recovery funds more equitably. “What we need to say is, ‘Who needs the money?’” he suggested. “And, ‘What areas need investment?’ And invest in such a way that it retains the character of the neighborhood prior to the event.”

People of faith also might help alleviate the disparity. Several options come to mind:

- Support the FEMA response Kashian proposed.

- Advocate for just and fair insurance regulation.

- Leverage financial clout to help low-income homeowners and landlords, first by making fairly priced insurance available and later by making low- or no-interest loans available for storm reconstruction.

- After twisters inflict their damage, think about others over self and resist the temptation to abandon the community.

Marv Knox

Marv Knox, founder of Fellowship Southwest following a long career in journalism, lives in Durham, N.C., but he was raised in the Texas Panhandle and has firsthand experience with tornadoes.

Related articles:

Tornado in ‘the buckle of the Bible Belt’ takes toll on houses of worship

Lessons for life and faith after a devastating tornado | Opinion by Doyle Sager

Churches playing role of chaplains in twister-torn communities