Standing at the crossroad of two gravel roads, one can turn in any direction to see wheat fields and cotton rows fade into a crimson haze on the horizon. Each road is pre-ordained to the straight and narrow by land surveyors marking off quarter sections 150 years ago. Creosote-soaked utility poles line the roadway, and they disappear into eternity, shouldering swooping black strands that carry power and occasional telephone calls between places one cannot see.

The crossroad is unremarkable in every way except where a barbed wire fence marks the perimeter of a small cemetery. In the far corner, overgrown cedar trees splash shade across a few dozen grave markers meandering to the north. A lonely headstone near the center of the plot is all that remains of the Ebenezer Mennonite Church, the name “Ebenezer” coming from a Hebrew phrase meaning “stone of help.”

Tim Krause

Nearly 100 years ago, on about that spot, in the middle of the church house about halfway between Gotebo and Mountain View, Okla., and at the epicenter of the American Dust Bowl, a young boy squirmed in the pew as Pastor Henry Hege’s sermon plodded into its second hour.

The summer heat already had rendered the boy’s Saturday night bath as aromatic history. A lock of brown hair sagged into his eyes, and his woolen suit pants stuck to his legs. The hot breeze offered scant relief, but it did deposit a thin coat of dust on the sill of the open window before rushing out the narthex door like a convicted sinner.

The young boy’s little brother, sitting next to him, was in similar shape. Their older sister, seated across on the other side of the room with the rest of the women, fanned herself vigorously with the order of worship. The pastor quoted from another epic sermon as he brought his own to a thirsty end: “For he makes his sun rise on evil and good, and he sends the rain on righteous and unrighteous.”

Pastor Hege’s doctrine had long arms as he cinched God’s providence over their 16th century forbears fleeing religious persecution up tight against the daily struggles of the sharecroppers in his pew. His elocution, delivered always and only in high German, was lost on the squirming kids who spoke a low form of German at home and English everywhere else. The young boy felt the power in the message, though, even if he didn’t understand it, and it stirred him in a way that never would leave him.

Seven hundred miles southeast of the Ebenezer church headstone, just at the edge of town in White Castle, La., a slender white steeple sprouts from the roof of the First Baptist Church. The ranch-style building’s buff brick façade is accentuated by a freshly mown front lawn. A covered walkway across the south parking lot connects worshipers to a steel building that contains an optimistic amount of education space.

The highway running past is the main thoroughfare into town, and it is the only barrier that seems to forestall vast sugar cane fields growing in the fertile Mississippi River bottom soil from enveloping the church and the town.

“The pastor’s name dangles precariously on a shingle below so that it can be easily changed without needing to repaint the whole sign.”

The sign out front advertising the name and the times of services isn’t much bigger than a Realtor’s yard sign. The pastor’s name dangles precariously on a shingle below so that it can be easily changed without needing to repaint the whole sign. More utility poles shouldering similar strands of cable traverse in front of the church, and their presence offers the first inkling of a long-distance connection between two far away churches.

The original white frame church building near the town center, directly across the street from the Catholic church, fell into disrepair and was sold to a developer in the early 1960s. The developer razed the church and the parsonage to make room for a commercial building. A concrete driveway apron leading from the street to nowhere is the only remaining artifact. The town, the fields and the church usually avoid periodic immersion when God sends a little too much rain upriver thanks to a massive levee that protects the community from the engorging river.

A decade after the church moved to its current location, automation had come to the sugar cane industry and eliminated most of the jobs, decimating the local economy. An unlikely visitor stopping in for morning worship on a typical Sunday will find fewer than 40 people in the pews, most of them of a certain age.

“The visitor might assume this is just an irrelevant rural church destined to be forgotten by the next generation.”

The visitor might assume this is just an irrelevant rural church destined to be forgotten by the next generation. Except, something — almost out of place — might catch his or her attention, like a granite headstone in the corner of a wheat field: A well-crafted sermon being delivered by a young, articulate preacher.

What the visitor would not realize is that the preacher is a student in the doctoral program at the Baptist seminary in New Orleans, about an hour and a half drive south. In fact, all 26 of the church’s pastors since 1940 were students at the same seminary.

Even as it continues to struggle with its own survival, the church offers a lifeline to these student preachers and to their futures. Many of them never could have afforded seminary without the weekly stipend. And the experience these student preachers are afforded by this church has an impact far beyond what any person can measure.

Those 26 students left that little church to spend careers spanning five continents. Some became pastors of churches in towns across America. Others were missionaries to Venezuela, Japan, Malaysia, Egypt and Germany. Some are still quite famous in the circles where they live. Many of them, though, already are as forgotten as an Oklahoma cemetery, as the trace lines of their influence fade with each generation.

Those 26 students left that little church to spend careers spanning five continents.

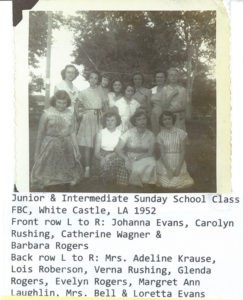

Only Lois Roberson, who lives in town near where the original church stood and now in her 80s, remembers one student preacher who grew up attending a small Mennonite church in southwest Oklahoma and arrived in White Castle with his wife in 1952.

“He was full of stories,” she said. “I was a teenager, and I liked to hear him preach. His wife was pretty, and we became friends.” She remembers that he used to come up early, on Saturday night, to watch boxing matches on TV with her dad.

“He was full of stories,” she said. “I was a teenager, and I liked to hear him preach. His wife was pretty, and we became friends.” She remembers that he used to come up early, on Saturday night, to watch boxing matches on TV with her dad.

The couple went on to become missionaries to Germany, where they nurtured dozens of new English-language churches throughout Europe. Most people who are in those congregations today — those churches that have survived the post-cold war withdrawal of American military personnel — would not know their names or anything about their work and certainly would not know anything the preacher said on any typical Sunday morning from the pulpit. When Lois is gone, the same will be true in her church for the memory of the young student preacher, his wife or their newborn baby.

This doesn’t mean that something important enough to remember didn’t happen in those places. The 16th century Mennonites fought through the adversity of persecution, the wheat farmers fought through the Dust Bowl, and the church fought through the automation of sugar cane farming. We all fight through our own struggles. We know we prevail because the Lord has helped us, and this is how we leave a marker for those who will never know us.

What is important is the stone that will have been left, the ebenezer.

As we begin to emerge from the pandemic and we take stock of what we have lost and what we have learned, how we have behaved in the face of adversity and how we should respond, we should look to the example of these soon-to-be-forgotten people and places.

Whether we sit in the pew or stand in the pulpit, what is written on the headstone we leave behind will be dictated by what we decide to do next, not by what we think others should or should not be doing now or in the future.

No headstone in any cemetery reads, “Here lies a saint who knew what everyone else should do.” We can, however, understand who has brought us to the time we occupy now.

“And in our moment, when we are faithful to the truth of that rich history, a headstone will stand there for each of us and for future generations.”

And in our moment, when we are faithful to the truth of that rich history, a headstone will stand there for each of us and for future generations after we have been long forgotten, all of them strung together like a line of creosote-soaked utility poles shouldering God’s unbroken story of humankind from before the beginning to an eternity we cannot see.

The truth of this history is found engraved on the headstone in the center of that Oklahoma cemetery about where my father sat squirming in his woolen suit so long ago. The inscription is taken from Samuel 7:12 where the Hebrew prophet placed an ebenezer on a hillside and proclaimed, “Hitherto hath the Lord helped us.”

Tim Krause is a writer and business consultant who lives in Dallas. He is the author of Finding Theo, a book about his young adult son’s journey after suffering a spinal cord injury from a mountain biking accident and the unlikely collection of people who came together to save him.