Americans have consistently lacked confidence in the United States criminal justice system and, once again, a majority views it as not tough enough. A national debate, ongoing for at least a century, attempts to solve the problem of crime.

Ironically, we often call this effort “the war on crime.” When war itself may be a crime, this seems an odd way to approach our current state of dis-ease.

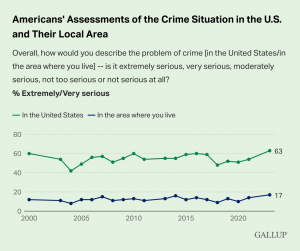

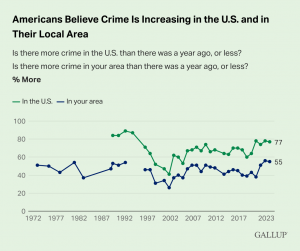

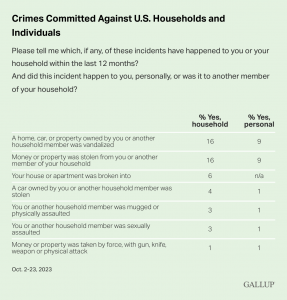

According to Gallup polls, more Americans want to see the criminal justice system get tougher on crime. The debate over crime and enforcement measures may be perceived as a statistical skirmish. Both sides throw around statistics exploding on the scene like Black Cat firecrackers on the Fourth of July. But statistics have limited value in debate. Not only do all sides of the debate have reams of statistical data, our “post-truth” culture now devalues what once was considered facts, proofs, evidence and solid information.

According to Gallup polls, more Americans want to see the criminal justice system get tougher on crime. The debate over crime and enforcement measures may be perceived as a statistical skirmish. Both sides throw around statistics exploding on the scene like Black Cat firecrackers on the Fourth of July. But statistics have limited value in debate. Not only do all sides of the debate have reams of statistical data, our “post-truth” culture now devalues what once was considered facts, proofs, evidence and solid information.

The people who seek to influence American public opinion often are locked into an outmoded notion that if people are just given the facts, they will reach logical and rational conclusions. Cognitive scientist Geroge Lakoff bluntly asserts, “If you believe something like this, you will be dead wrong.”

Statistics, however, still have value in providing background information and foundations for the vigorous debates about crime in the U.S.

Megan Brenan, in an article titled “Americans More Critical of U.S. Criminal Justice System,” reports:

- 58% say the criminal justice system is not tough enough, up 17 points since 2020.

- 49% think the criminal justice system is fair, down from 66% in 2003.

- More white adults than people of color say the system is fair, not tough enough.

In the current survey, three-quarters of Republicans think the criminal justice system is not tough enough, 16% say it is about right, and 7% believe it is too tough. Democrats are more divided in their views, with a 42% plurality saying it is not tough enough, 35% about right and 20% too tough.

While a 63% majority of white adults say the criminal justice system is not tough enough, fewer people of color (49%) agree. Another 29% of people of color think the system is about right (compared with 24% of white adults), and 20% say it is too tough, which is slightly higher than the 12% of white adults who say the same.

Emotions drive American attitudes about crime

The issues are more about emotions than statistics. Understanding the attitudes of Americans toward crime and enforcement requires attention to the dynamics of affects (emotions).

Below the surface of increased pressure for stricter law enforcement, added police presence and longer sentences are an array of American demons. Debating the facts about crime leads to a standoff with hostages thrown in. No progress can be made until we face our demons. These demons have biblical, historical, political and sociological components.

Fear

Fear covers America like an impregnable dome dropped out of the sky. Even if people are not fearful by nature, it is in the air we breathe, the news and programs we watch, the social media we read, the conspiracy theories we imbibe, and the politics that dominate our system. We catch fear by osmosis.

Fear stems from legitimate concerns such as crime. Our politicians take our legitimate concerns and turn them into apocalyptic threats to our security and safety.

The apocalyptic rains are falling, and the winds are howling, and we are afraid we have built our national house on shifting sands.

For instance, David Brooks has intoned, “America is falling apart at the seams.” It is sober commentary on the rise of hostility Americans are showing to each other.

John Fea, in Believe Me, identifies fear as a major motivating factor among American evangelicals. Anna M. Young in “Rhetoric of Fear and Loathing: Donald Trump’s Populist Style” argues our politics are controlled by irrational fears.

John Fea, in Believe Me, identifies fear as a major motivating factor among American evangelicals. Anna M. Young in “Rhetoric of Fear and Loathing: Donald Trump’s Populist Style” argues our politics are controlled by irrational fears.

As the gates of Eden closed forever, fear walked out into the world with Adam and Eve. While I have no patience with notions of “original sin” passed on in the blood of Adam, I am convinced fear haunts all humanity.

The message sounds everywhere: The nation is falling apart, the nation’s faith is unraveling, the barbarians are at the gates (borders), and the enemies are within. Fear, fear and more fear.

Fea argues, “Fear is the political language conservative Christians know best.”

Religious fear

Evangelicals have been dishing out fear since the first English settlers arrived on the East coast. The culture of fear came to America on the Mayflower. The shadow haunting Winthrop’s vision of the “city on a hill” was fear. From the Puritan attempts to create a society free of sin and crime to the wrath of God in Jonathan Edwards’ “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” fear has dogged every step of every American from the beginning to the present moment.

The fear of moral and spiritual decline in the 17th century is mirrored by the same fear in our day. Each generation of evangelicals added new out-groups to fear: the Catholic menace, the infidels and atheists, the scientists of evolution, the critical scholars of the Bible, the communists, the African Americans and now, all these fears morphed into the fundamentalist fear of radical liberal, feminist, atheist, unpatriotic Americans attempting to destroy the Christian way of life.

Political fear

There’s an apostolic succession of fearmongering in America — passed along to each new generation. The fear resonates from every pore of the political demagogue’s resentment, nativism, nationalism, triumphalism — in a mixture of economic angst, racism, religious bigotry, antifeminism and hostility toward science, the mainstream press and the establishment in general.

During the 1990s, two-thirds of Americans believed crime was rising, when in fact the crime rate was dropping. Conservative politicians fed the engine of fear around the subject of crime.

The politics of fear provides the emotional fervor to our attitudes toward crime. Importantly, said Daniel Patrick Moynihan, there is always some factual basis to conspiracy theories (for example, an increase in the number of Mexican migrants in the United States), even though the extrapolations from those data (immigrants commit more violent crimes) often are baseless.

Media-generated fear

Conservative media spreads the fear. Laura Ingraham, for instance, has, like so many others in the Fox universe, depicted illegal immigrants as thieves and murderers, despite overwhelming evidence that immigrants commit fewer crimes overall than native-born Americans. Thus, she has called for an end to all immigration.

Conservative media spreads the fear. Laura Ingraham, for instance, has, like so many others in the Fox universe, depicted illegal immigrants as thieves and murderers, despite overwhelming evidence that immigrants commit fewer crimes overall than native-born Americans. Thus, she has called for an end to all immigration.

Some media outlets sensationalize crime. “If it bleeds, it leads.” Attitudes toward crime often are constructed around our experiences of watching crime reporting on TV news.

Also consider is the large number of crime shows that comprise so much of our visual entertainment. Chicago PD., NCIS,FBI, FBI International, FBI Most Wanted, Law and Order, Law and Order SVU, East New York, Blue Bloods, and The Equalizer are top-rated television shows.

“Politicians are savvy enough to know that tough talk on crime works because it fits what people see on the news every day.”

Kathleen Jamison in Dirty Politics shows how the language of political ads about crime became the language of the national news. “Substantive” reporting allows itself to be shaped by artful consultants skilled in the use of emotional appeals and misinformation. Politicians are savvy enough to know that tough talk on crime works because it fits what people see on the news every day.

Politicians have effectively used audience psychology and emotional appeals to color attitudes toward crime. The rhetoric of George Bush, for example, transformed Willie Horton’s name for some into a symbol of the terrors of crime. And every claim in the ad about Horton was either false or an outright lie.

The personalizing of appeals involves an intensification of emotions. Rodney King, Willie Horton, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Alton Sterling, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and Dante White are a few of the names that have intensified the debates swirling around crime, race and police methods.

Levitical issues

From a biblical perspective, attitudes toward law and order are a Levitical argument. There are a growing number of Levitical Christians in the U.S. variously described as evangelicals or Christian nationalists or right-wing believers. Will Campbell once said, “If you want to sentence someone to death in the South, all you need is a jury of 12 good Baptist deacons.”

Leviticus never met an action or a thought that it was hesitant to criminalize. In the pages of this Hebrew Scripture are the origins of what George Will labels “overcriminalization.” Will suggests we now operate a “broken windows” policing along with decades of “overcriminalization.”

“The policing applies the wisdom that when signs of disorder, such as broken windows, proliferate and persist, there is a general diminution of restraint and good comportment. So, because minor infractions are, cumulatively, not minor, police should not be lackadaisical about offenses such as jumping over subway turnstiles,” Will says, concluding that overcriminalization has become a national plague.

The death penalty was prescribed for 36 offenses in the Old Testament, including sassing your mother and having a dangerous ox. For instance, false prophets whose prophecies do not come to pass are sentenced to death (That might give rapture prophets pause). Then there was working on the Sabbath, adultery, pretending to be a virgin, and disobeying one’s parents. And one especially intriguing: “disobeying a court order.”

“Leviticus never leaves the imagination of many Christians.”

The current Christian infatuation with Leviticus and its propensity for harsh punishment extends to the anti-abortion movement. Strict anti-abortionists are attempting to add the death penalty for women who have abortions, doctors who perform abortions, and even friends who drive a pregnant woman across state lines for an abortion. Leviticus never leaves the imagination of many Christians.

Christians should offer at least the story of God’s reluctance to engage in such behavior. The story of Cain remains instructive. “And the Lord put a mark on Cain, so that no one who came upon him would kill him. Then Cain went away from the presence of the Lord, and settled in the land of Nod, east of Eden” (Genesis 4:15–16). The mark of mercy mitigates the brutish desires for more punishment. And that mark of mercy burst the bounds of human understanding in the death of Jesus on the Cross. The Cross — God’s ultimate sign of mercy — marks all humanity for life.

The book of Numbers also mitigates the harshness of Leviticus with “refuge cities.” It says: “The towns that you give to the Levites shall include the six cities of refuge, where you shall permit a slayer to flee, and in addition to them you shall give 42 towns.

Authoritarianism

The desire for more control over crime issues from rising authoritarianism in America. People desire security, safety and control. They are susceptible to authoritarian promises to provide all these desires in exchange for giving up freedom.

The dogma of escalating authoritarianism arises from an understandable paranoia toward potential terrorists, our traditional fear of too many liberties and our deep distrust of one another.

The tragedy of escalating authoritarianism: It makes victims of even ardent supporters. It tightens the rope around one’s own neck. As 1 Samuel 2:9 asserts, we will not prevail by force.

A fundamentalist strain of Christianity, rooted in claims of biblical and pastoral authority, has gained far too much power in our political system. Cornel West argues this Christian fundamentalism is violating fundamental principles enshrined in the Constitution; it is also providing support and “cover” for the imperialist aims of empire.

The Jesus way

If we can tear ourselves away from the siren calls of getting tough on crime, perhaps we can once again seriously consider the teaching of Jesus.

In his first sermon, announcing the arrival of God’s kingdom, Jesus says, “He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives.” Now, here’s a countercultural move against longer sentences, more prisons and a crackdown on crime. Jesus’ call for release of prisoners stands opposite all calls for more incarceration.

“Jesus’ call for release of prisoners stands opposite all calls for more incarceration.”

Hanging on the Cross as a condemned criminal, terrorist and seditionist, Jesus continued his work of mercy by accepting one of the thieves into the kingdom while both were dying.

In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus instructs his followers not to go by an eye for an eye. He creatively reinterprets Leviticus by bursting open the previously barred gates to all humanity as neighbors.

An analogy from television

The Last Enemy is a five-part BBC television series that brings laser focus to a near-future London beset by crime, terrorism and illegal immigration. At the heart of the program is a computer program known as TIA, short for Total Information Awareness. The centralized database tracks and monitors everyone, effectively controlling the population.

The audience gets a feeling TIA may not be worth the loss of freedom it entails. Even more ironic, the story reveals a political cover-up based on a government-sanctioned but secret medical experiment gone bad, with key members of the government attempting to hide the evidence of their terrorist act that kills thousands of people. The people controlling TIA become criminals and terrorists.

TIA unpacks the moral, social, freedom and privacy concerns we now face. A belief that our government should be tougher on crime has the potential to lead to a TIA world. In this series, the audience sees control mechanisms that are already in use in modern life, such as retinal scans, fingerprint identification, DNA and the ever-present camera and cellphone surveillance.

The story raises more questions than it answers as the protagonist becomes a pawn in a manipulative security state. Perhaps The Last Enemy serves as one more alarm to the dangers of too much security and control.

I am convinced fear and authoritarianism are anathema to democracy and Christianity.

Rodney Kennedy

Rodney W. Kennedy is a pastor and writer in New York state. He is the author of 10 books, including his latest, Good and Evil in the Garden of Democracy.