Another season of the so-called “war on Christmas,” especially in the wake of Donald Trump’s election, may be just enough to drive some people over the edge.

And all indications are it isn’t going to go away.

“There is no easier way for politicians or pundits to rally the base this time of year than hyping the ‘War on Christmas’ by liberal elites,” Baylor University history professor Thomas Kidd said in a book review of Gerry Bowler’s Christmas in the Crosshairs: Two Thousand Years of Denouncing and Defending the World’s Most Celebrated Holiday.

“Donald Trump’s son Eric told evangelist James Robison in an August interview that one reason Trump decided to run for president was because the White House ‘Christmas tree’ was now called the “holiday tree,’” Kidd writes, adding that multiple sources say the change never occurred.

In his Christianity Today piece, Kidd presents Bowler’s account of the love-hate affair some Christians have had toward Christianity through the centuries.

Religion scholars are not surprised conservative evangelicals herald the holiday today, when their Puritan ancestors banned it for being too Catholic and pagan. And they have taken just about every position in-between.

But what is consistent is the battle, said Andrew Gardner, a doctoral student in American religious history and author of the 2015 book Reimaging Zion: A History of the Alliance of Baptists.

“There is nothing new under the sun,” Gardner told Baptist News Global. “That reminds me that we’re constantly undergoing a negotiation as to what Christmas means.”

The constant back-and-forth, Gardner said, is about the symbols inherent in Christmas.

“Anytime you’re dealing with symbols you’re constantly negotiating over what they mean.”

For some, Christmas symbolizes the incarnation. For others, it’s about decorated trees and time for family. For some, it’s time off from work and gift-giving. While others see it as a sign of their faith’s place in the culture.

Other issues that have shared that kind of back-and-forth are Ten Commandments and prayer in school debates, Gardner said.

“Another example is communion and what communion means, and Baptists in particular do that a lot,” he said.

From Puritans to Westboro Baptist

The Christmas tug-of-war began early, Kidd writes in his review of Bowler’s book, which was published in October by Oxford University Press

The Christmas tug-of-war began early, Kidd writes in his review of Bowler’s book, which was published in October by Oxford University Press

Some early Protestants saw the holiday negatively because it was tied to the Catholic Church. They believed it to be Rome’s attempt to Christianize a pagan festival.

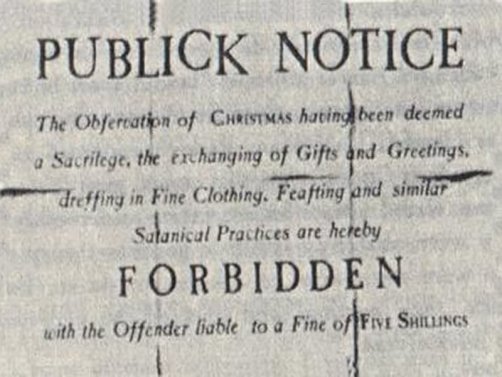

“In the 1640s, the Puritan-dominated English Parliament banned Christmas. …’” Kidd writes.

The holiday’s prospects improved around the early 19th century with the works of Charles Dickens and others. The 1822 publication of a story known as “’Twas the Night Before Christmas” is also considered a pivotal moment, Kidd writes.

“The gift-giving Santa also transformed Christmas into the merchants’ holiday par excellence,” he added.

The book also provides modern examples of the tug-of-war over Christmas. These include Westboro Baptist’s replacement of “Santa Claus is comin’ to Town” with “Santa Claus Will Take You to Hell.” Planned Parenthood, Bowler reported, offered a version of the “Twelve Days of Christmas” in which a lover offers family-planning gifts to his beloved.

And there are ACLU and other secularists’ efforts to remove Christmas symbols from the public square.

Bowler is opposed to both of the spectrum in the ongoing culture battle, according to Kidd.

Part of the problem, Gardner added, is that Christmas has become a secular, national holiday. That makes the debate over its meaning particularly complex.

“Any time you have something this fluid and this malleable, you’re always going to go through this negotiating,” Gardner said.

And for that reason, there is little hope the rhetoric is going to stop.

“In 10 to 15 years it may not be about Christmas, but it will be about other things,” he said.