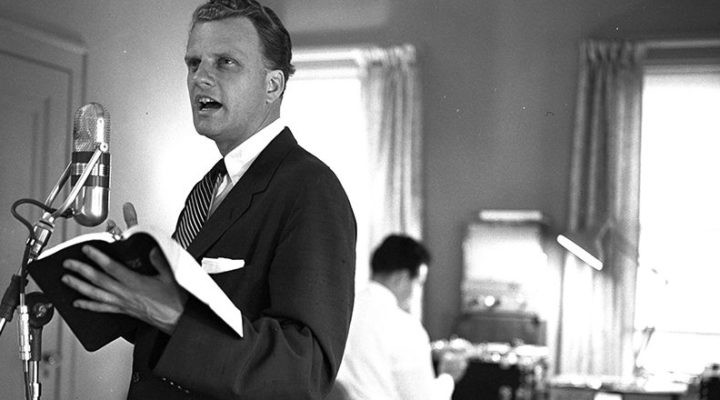

In 1950, evangelist Billy Graham initiated a radio program called the “Hour of Decision,” an audio vehicle for dispensing the call to conversion on the airwaves of America and the world. Actually, it was only a 30-minute broadcast, but what self-respecting evangelist would invite sinners to a mere “Half-hour of Decision?”

Sponsored by the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, the “Hour of Decision” endured until 2016, hosted throughout most of its history by Graham’s longtime colleague and musical director, Cliff Barrows. The format included a sermon by Graham or members of his “team,” and music from soloists or crusade choirs, concluding with an invitation for unconverted listeners to make “the decision,” accepting Christ as Savior by praying the “sinner’s prayer.”

Bill Leonard

Proclaiming that gospel message in mass revival crusades, publications, films and the “Hour of Decision,” evangelist Graham was a major figure in defining modern American evangelicalism.

The “Hour of Decision” came immediately to my mind after reading a recently released letter to Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R-Ill.) from certain evangelical members of his family. The handwritten missive, dated Jan. 8, 2021, begins: “Oh my, what a disappointment (multiple underlining) you are to us and to God!” It goes downhill from there, words from a family furious that their kinsman voted to impeach their president.

“President Trump is not perfect,” the letter continues, “but neither are you.” It notes that Franklin Graham, Robert Jeffress and other of Trump’s pastoral “mentors” “know that he is a believer,” and cites the president’s “Christmas Message,” “where he actually gave the plan of salvation, instructing people how to repent and ask the Savior into their heart to be ‘Born Again”!

The 11 signers contend that while more “grievances” could be enumerated, they “decided you are not worth much more of our time,” and collectively declare: “It is now most embarrassing to us that we are related to you.” (Guess that’s why they didn’t close with “yours in Christ!”)

This deeply personal, sadly public epistle is a microcosm of divisions seeping into the fabric of American culture from legislative enclaves to political parties, town councils, churches and multitudes of extended families. For many Christians, enduring debates over Scripture and doctrine, social and political action, and the very nature of the gospel itself often come down to one brief confession of faith: “Donald Trump, are you for or against him?”

In 2021, after four years of political intrigue and unrest, culminating in a Capitol insurrection and resulting impeachment trial, what will be the immediate if not lasting impact on American evangelicals across the political spectrum? Is this their own hour of decision as to the meaning and method of their Christian identity and witness inside and outside the church? As to where the gospel will take them or will they take the gospel, post-Trump?

“American evangelicals are clearly at a crossroads for determining who they are and what they are about.”

Whatever their politics, American evangelicals are clearly at a crossroads for determining who they are and what they are about, not simply in Washington, D.C., but also in the kingdom of God.

Some are already revisiting the “evangelical quadrilateral” set forth by British scholar David Bebbington, in describing most salient features, including: 1) a conversion experience (new birth) marking entry into Christian faith; 2) a strenuous biblicism that anchors faith to scriptural authority; 3) the centrality of the cross event as Christ’s unique act of gospel redemption; 4) an evangelical activism by which born-again individuals share their faith with others.

More recently, given the substantive support of some evangelicals for the person and work of Donald Trump, Bebbington’s quadrilateral has come under criticism from those who suggest that its four points may be too general to explain certain religio-political positions of many of its adherents.

Independent scholar Timothy Gloege writes that, “conversion’s unmeasurable quality is what makes it useful for insiders,” thereby allowing anti-Trumpers to suggest that his supporters are evangelical drop-outs, while pro-Trumpers assert that “never-Trump evangelicals have demonstrated their faithlessness.” Gloege adds: “Liberal evangelicals also have a calculus of conversion that excludes their conservative rivals. Conversion (thus) acts as a theological weapon that muddies the definitional waters; it’s not an analytical category.”

Messiah College historian John Fea acknowledges the value of Gloege’s critique while affirming the quadrilateral as a clarifying tool. Fea expresses “hope that because my fellow evangelicals believe in an inspired Bible, or a conversion (‘born-again’) experience that results in holy living, or the command to share their faith with others, they can be persuaded that racism or nativism or Trumpism may not be the best way to be ‘evangelical’ in this world.”

Right now, were I to tinker with my friend Professor Bebbington’s quadrilateral, I’d suggest adding that evangelicals believe that the exercise of individual conscience is essential for all who claim and are claimed by God’s grace in Christ. Martin Luther articulated this “evangelical” grace in his declaration that, “My conscience is captive to the word of God.” The presence or lack of individual conscience is the great test that confronts us all in the Trump era.

“The presence or lack of individual conscience is the great test that confronts us all in the Trump era.”

Indeed, two revelations from Trump’s response to the Jan. 6 insurrection, made known at the second impeachment trial, dramatically illustrate the need for and absence of acts of conscience on the former president’s behalf. The first was the acknowledgement that shortly after Trump learned that Vice President Mike Pence, a committed evangelical Christian, had been evacuated from the Senate chamber where he was presiding over the electoral vote count, Trump quickly tweeted: “Mike Pence didn’t have the courage to do what should have been done to protect our Country and our Constitution.”

That post, immediately available to the invading mob, paralleled the chant, “Hang Mike Pence,” echoing in the Capitol’s hallowed halls, where Pence and his family spent hours in hiding, their escape just in the nick of time captured on security cameras. Trump’s knowledge of the Pence family’s evacuation from the Senate chamber was confirmed by Tommy Tuberville (R-Ala.), who reported that Trump called him to insist that he delay the ballot count from the electors. Tuberville, a major Trump ally, then told the president what was occurring in the chamber. Still, Trump made no effort to send reinforcements. Where was his conscience at that decisive moment? Were Pence and his family expendable? At that moment, the troops and the president’s conscience were nowhere to be found.

A second, related event occurred when House minority leader Kevin McCarthy telephoned Trump later that January afternoon to plead with him to send troops to the increasingly occupied Capitol. Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler (R-Wash.) gave this written testimony at the impeachment trial: “When (Kevin) McCarthy finally reached the president on Jan. 6 and asked him to publicly and forcefully call off the riot, the president initially repeated the falsehood that it was antifa that had breached the Capitol. McCarthy refuted that and told the president that these were Trump supporters. That’s when, according to McCarthy, the president said, ‘Well, Kevin, I guess these people are more upset about the election than you are.’” (Her italics.) Again, troops were not immediately sent to the Capitol — the president’s conscience nowhere to be found. Would ours have remained intact?

So what about evangelicals and the rest of us, our consciences, convictions and conversions? Vanderbilt professor and presidential historian Jon Meacham summed it up for me on the Monday after the impeachment trial ended when he recalled a passage from Tom Sawyer, where Tom says that “an evangelist came to town who was so good that even Huck Finn was saved until Tuesday.” That’s a sobering reminder to all of us, don’t you think?

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.