I was making omelets in the kitchen when I heard the familiar voice of Foster Hewitt coming from the living room. I grew up listening to hockey games on the radio, and Hewitt’s “He shoots, HE SCORESS!!!” is imbedded in the psyche of every Canadian of a certain age.

It turned out that Micah, my toddler grandson, had been fiddling with the TV remote and inadvertently had landed on a documentary about the 1972 “Summit Series” between Team Canada and the Soviet Union. I was overwhelmed by a sudden rush of memory and deep emotion.

Alan Bean

When I was coming up, hockey was Canada’s game. In the early 1960s, we were still sending amateur teams to international competitions. We always won. And then we usually won. By the mid-1960s, we were starting to lose. The Soviet national team trained constantly and played like a well-oiled machine. But in Canada, it was an article of faith that the hated Soviets would be soundly trounced if they were forced to play a team of NHL all-stars.

In 1972, this theory was put to the test. Eight games were scheduled between Team Canada (all NHL all-stars) and the Soviet national team. The first four games were played in Canadian cities; the last four were slated for Moscow.

The Canadian players stayed in game one through two periods, but the superior conditioning of the opposition finally took its toll. The Soviets won 7-3. Team Canada won a game and tied another. But another lopsided loss in game four brought raucous boos cascading from the stands. Interviewed after the game, team captain Phil Esposito let the Canadian public know how disgusted he was by their behavior.

But who could blame us? No one knew how much Canadian national identity was tied to hockey supremacy until the myth was shattered. When Canada dropped the first game in Moscow, the national humiliation was complete. Then something changed. Their backs to the wall, the Canadian team started playing like men possessed. Games six and seven, both squeakers, went to Team Canada.

“No one knew how much Canadian national identity was tied to hockey supremacy until the myth was shattered.”

Three-quarters of the Canadian population tuned in for a climactic game eight. School lessons were canceled so everyone could watch the game. Playing most of the first two periods with a man in the penalty box, Team Canada fell behind 5-3. The chill of impending disaster spread across Canada.

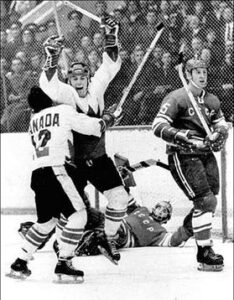

But Canada scored a goal, then another. With just 34 seconds remaining, Canada’s Paul Henderson banged in a rebound, igniting a nationwide celebration. I still get choked up thinking about it.

Paul Henderson celebrates the series-winning goal while being embraced by Cournoyer. The award-winning photograph, taken by Frank Lennon, has been called “one of the ten images that changed Canada.” (Wikipedia)

National humiliation had been averted, but the Summit Series blew the myth of Canadian ice hockey dominance out of the water. We hadn’t dominated international hockey because we were stronger, braver or more resilient than the people of other northern nations. Our post-war success was a function of climate, economics and the fact that Europeans were slow to embrace our game. Our narrow victory in 1972 owed more to desperation and good luck than anything else. In 1972, 95% of NHL players were Canadian; today, 57% of the league’s players are Americans and Europeans.

I’m telling you this story because it helps me identify with American white evangelicals. America once fancied itself the greatest nation on the face of the earth. And this was so, white evangelicals told one another, because America was a bastion of evangelical Christianity.

But America also was great because America was white. In the halcyon days after World War II, 88% of the American population was white. The tenets of white supremacy and divine favor intermingled without embarrassment.

In 1953, the year of my birth, only one in three women were in the work force, LGBTQ persons were in the closet, and the Civil Rights movement was just getting organized. Meanwhile, rates of church attendance were at all-time highs. The best way to keep the good times rolling, most white evangelicals assumed, was to preserve the status quo. God liked America just the way she was.

Then it all started falling apart. White males enjoyed a lock on power, feminists and civil rights activists declared, because the game was rigged in their favor. White evangelical men still controlled the social, political and religious life of the nation, but they had been forced into a defensive crouch. If the American game was rigged, critics argued, the winners had blood on their hands.

In a scene from the Mary Tyler Moore Show, Ted Baxter, a blowhard news anchor, asked Lou Grant for some pre-marital advice. “Ted,” Grant replied after a pregnant pause, “you know the way you are? Don’t be like that.”

This is the message white evangelical males had been hearing for decades when Donald Trump rode his golden escalator to glory. For years, the message had been muted. Prior to the 1990s, most Americans got their news from the three major television networks. Strict neutrality was the order of the day. Conservatives eager to argue against affirmative action, gay rights and the Equal Rights Amendment found themselves sitting across the table from their ideological opposites. Preachers, politicians and pundits shied away from controversy. As Johnny Carson, host of the Tonight Show, once explained, “Why would I want to alienate half my audience?”

“This is the message white evangelical males had been hearing for decades when Donald Trump rode his golden escalator to glory.”

Meanwhile, all the culture war victories were going to the liberals. Brown v. Board of Education. Roe v. Wade. Women were running for elected office; they were gaining a toehold in the boardrooms of the nation. Some were even preaching. The gay rights movement was tacking into a stiff wind, to be sure, but progress was real and rapid. Although still underrepresented, African Americans were becoming more visible on television, in the movies, on the evening news, even in Congress.

Conservative America had the Reagan Revolution to cheer about, but meaningful gains were largely confined to fiscal policy, military expansion and tough-on-crime legislation. White evangelicals felt used and disrespected by their political allies.

Although America was ideologically divided, elite opinion, especially in the coastal cities that controlled mass messaging, tended to skew left. From Hollywood producers to Saturday Night Live to the editorial board of the New York Times, a cautious center-left orthodoxy was constantly reinforced.

The message to white evangelicals was clear: “You know the way you are? Don’t be like that!”

Aleksandr Maltsev #10 of the Soviet Union and Red Berenson #15 of Canada battle for the puck during the 1972 Summit Series at the Luzhniki Ice Palace in Moscow, Russia. (Photo by Melchior DiGiacomo/Getty Images)

Then the times began to change. Much like Team Canada in 1972, American conservatives rallied. In 1987, the “fairness doctrine” that forced broadcast networks to give equal air time to both sides of an issue was rescinded. Beginning in the early 1990s, Rush Limbaugh and a new crop of entrepreneurial talk show hosts took the nation by storm. In 1996, the Fox News Network provided a conservative alternative to mainstream media.

As America moved into the 21st century, white evangelicals no longer were forced to abide liberal talking points. They could take their Christian nationalism straight. It was as if Canada had claimed ice hockey supremacy in 1972 without having to lace up their skates and prove it.

On the hard right, public policy discussions became more like professional wrestling than legitimate sport. Whether you were talking about television, radio or religion, ratings were everything. Limbaugh’s ditto-heads were 100% on his side because he was 100% on theirs. “My objective is to satisfy my audience,” he explained in 2009, “so they come back the next day.”

Limbaugh appealed to generic conservatives: white males, evangelical Christians, right-wing Republicans, and the denizens of flyover America. He told these people their past dominance had been earned. It was theirs by right. Power was a matter of perseverance, not privilege.

As the white slice of the American pie fell from 75%, when Limbaugh got rolling in 1992, to 58% the year he died, the appetite for his convenient lies multiplied. The ritual denigration of feminists, people of color and the LGBTQ community worked with political conservatives, Limbaugh fans, white evangelicals and, increasingly, Republican voters.

These categories can be distinguished, of course, but their response to Limbaugh’s brand of white racial grievance was virtually identical. White evangelicals should have been defined by essential Christian virtues like compassion, empathy, mercy and radical forgiveness. Conservative talk radio proved they were not.

“White evangelicals should have been defined by essential Christian virtues like compassion, empathy, mercy and radical forgiveness. Conservative talk radio proved they were not.”

Limbaugh’s schtick dovetailed perfectly with Christian radio: white male grievance lay at the heart of the message. Limbaugh may have mocked traditional Christian virtues like mercy, humility and compassion, but that’s why white evangelicals loved him. In the beginning, he attended to the wounded pride of conservative America because that’s where the money was. But, over time, he began to believe his own message. He was high on his own supply.

When Donald Trump decided to run for president in 2015, the Republican establishment and the leaders of the Religious Right were initially dismissive. The man was crude, he owned casinos and strip clubs, and he treated marriage as a temporary convenience. More to the point, he had no clue how to adapt his vulgar vocabulary to a religious audience.

But it was quickly apparent that Trump understood white evangelicals perfectly. They were bristling with racial resentment. They were dying for affirmation and reassurance. They were weary of being ignored, caricatured and stigmatized. They cheered every time Trump trampled the canons of political correctness. They applauded when he questioned the citizenship of Barack Obama. They rejoiced when he bragged about building a border wall and making the Mexicans pay for it.

“You know the way you are?” Trump told evangelicals. “I love it!”

His audience ate it up. It was like Paul Henderson banging home the winning goal in game eight of the Summit Series!

Trump wasn’t just talking. In his book Insurgency: How Republicans Lost Their Party and Got Everything They Ever Wanted, Jeremy W. Peters features Trump’s relationship with white conservatives.

When evangelical leaders gathered to pray over then-President Donald Trump, Robert Jeffress of First Baptist Church of Dallas (hand help up) was among them but Russell Moore of the SBC Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission was not.

“He invited Republican activists to small, formal dinners in the Blue Room and policy discussions in the Roosevelt Room. He inquired constantly about his standing with them. ‘Do Christians know all I’m doing for them?’ he asked at one dinner in the Blue Room with conservative activists. ‘Do the pro-lifers like me?’ he asked a golfing companion. Indeed, they did.”

But the love flowed in both directions. In the heart of the Cold War, white evangelicals were critical of authoritarian regimes; after Trump, this concern evaporated. When Trump came on the scene, evangelicals decided personal rectitude was over-rated.

Hugh Hewitt, one of Limbaugh’s heirs, was devoutly anti-Trump until he realized it was bad for business. In a recent discussion with Chris Christie, Hewitt gave away the game. “I never talk about January 6, because I like my audience,” Hewitt told his guest, “I don’t want them to turn me off.”

Hewitt knows his audience. Recent polls suggest that 60% of Americans strongly disapprove of the behavior of the people who stormed the Capitol and 57% believe Trump bears a great deal of responsibility for what happened. But 28% of respondents characterized the rioters as “patriots” and “freedom fighters.” These are the people, many of them white evangelicals, who tune into conservative talk radio.

The conservative echo chamber was destined to produce conspiracy theories like QAnon and the “Big Lie” that Trump won the 2020 election. Something along the order of COVID-19 misinformation and January 6 denialism were virtually inevitable. A movement grounded in fantasy cannot adapt to the real world.

“Before Trump threw his hat into the presidential ring, few grasped how much white male grievance defined American white evangelicalism.”

Before the Summit Series, no one realized how much dominance in international ice hockey meant to Canadians. Similarly, before Trump threw his hat into the presidential ring, few grasped how much white male grievance defined American white evangelicalism. Now, to our sorrow, we know.

Backs-to-the-wall desperation allowed Team Canada to prevail against the Soviets in 1972. In similar fashion, last-ditch despair drove white evangelicals to line up behind Donald Trump in 2016.

White evangelical desperation is a powerful force. It won an election and has allowed religious conservatives to commandeer an entire political party. But history will not be kind to Trump or his evangelical enablers. Like Canadian hockey players, white evangelical males eventually will have to compete on a level sheet of ice. Desperation can breathe new life into a lie; but it will never serve as a long-term strategy.

Alan Bean is executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas.

Related articles:

Choose you this day whom you will serve, Truth or Trump | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

The Trump Card: How white evangelicals are being played | Opinion by Joel Bowman Sr.

From 2016 to 2020, Trump grew in support from white evangelicals