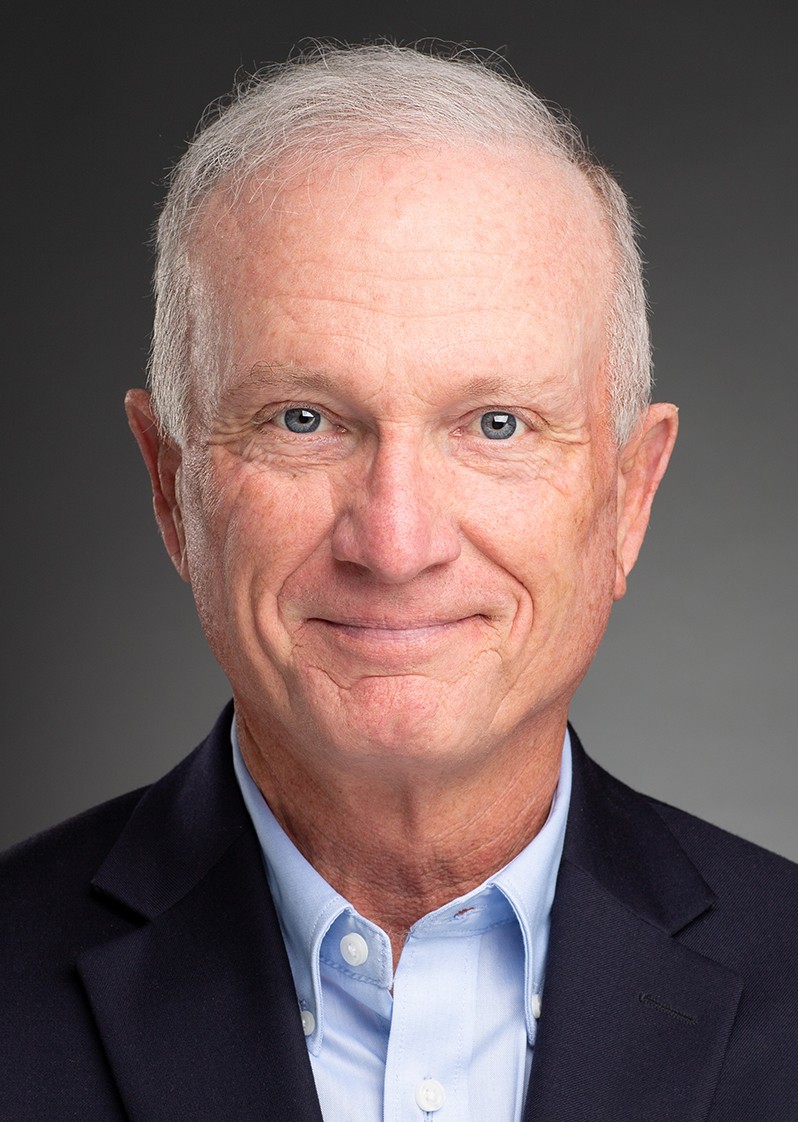

This is the final column written by David Ramsey before his untimely death Dec. 11. This submission was sent to BNG on Dec. 9, less than 48 hours before his death. See the related obituary also published today.

In “Artificial Minds and the Coming Religious Disruption,” Yale Divinity School professor John Pittard examines the intersection of two seemingly disparate fields, theology and technology, and the conflicts the latter might pose to churches and their leaders in the not too distant future.

Pittard draws on an argument by a Google engineer that a chatbot is a sentient being. While Google has dismissed this claim (and the engineer who made it) Pittard suggests it is “not implausible to think that within a generation, human beings will have produced (Artificial Intelligence) interlocutors that some experts and many non-experts will deem to be conscious.”

David Ramsey

If true, Pittard argues, churches may experience conflict over the spiritual status of such, uh, “things” and will need to prepare for the challenges they pose, like if a parishioner asks a pastor if she can bring her AI friend to Sunday School.

I’ve found myself vacillating between bemusement and amusement thinking about this “challenge,” and I’m more than a bit qualified to inveigh on the subject. I spent 10 years studying religion in academic settings and another 10 as a Baptist minister. For the last 25 years, I’ve lived in the world of technology, the last eight of which have been spent at one of the world’s largest tech companies, Amazon. If my life were a Venn diagram, it would look like the intersection of theology and technology.

First things first. It’s called “artificial intelligence,” for a reason. It’s artificial, as in not natural. The adjective alone should be a huge tell and end all further discussion. But Pittard continues, and so shall I.

Pittard suggests: “We have no firm basis for determining whether an AI-enabled being has what it takes to be sentient.” Really? If “sentient” means the ability to perceive or feel things, how can a bot ever experience the joy that accompanies the birth of a child? Or the grief from the death of that same child? Where and who is Buber’s Thou in a bot?

I also take exception with Pittard’s argument that “Christians and other theists have ways of explaining consciousness that are not available to secular atheists,” namely, theism. Theology is available to everyone; however, it doesn’t explain anything. It is a belief system. I would agree, though, with Pittard’s statement that, “from a hard-nosed scientific perspective, consciousness appears to be explanatorily superfluous and thus an inexplicable mystery.”

“If your church’s most intractable problem is what to do when a member brings her AI friend to Bible study, consider your congregation quite fortunate, or blessed.”

My bemusement turns to amusement when Pittard suggests that AI may pose “challenges” to the church. If your church’s most intractable problem is what to do when a member brings her AI friend to Bible study, consider your congregation quite fortunate, or blessed.

Many churches are struggling to get bodies, not bots, into their buildings. Declining attendance in the U.S. is well documented. How and if you should baptize a bot isn’t. (But in this case, I suggest sprinkling versus immersion).

Artificial intelligence is solving incredibly complex and important problems. One bio-pharmaceutical company runs more than 51 billion statistical genomics tests in under 24 hours using AI. Bringing a single, life-saving drug to market takes an average of 10 years and more than $1 billion. AI accelerates this process with a higher probability of success.

I do not know, however, if or how AI can stem declining church attendance. Even if it can, it faces another perennial parish problem: how to get members to support the congregation financially.

Because say what you want about artificial intelligence, bots can’t tithe. Or can they?