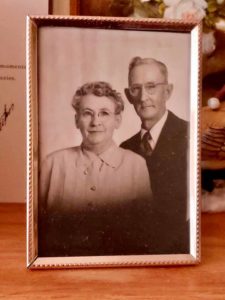

Roy and Delyte Cantwell of Independence, Mo., both at the age of 32, in early 1956 began the arduous process of adopting a child since they were not able to have a child in the usual way.

On Feb. 28, 1957, they brought me to their home when I was six weeks old. Roy and Delyte, Dad and Mom, loved me, no doubt. They provided for me. They did their very best to parent me in the most effective ways they knew how.

I have always wondered about, prayed for and wanted to meet my birth parents, If not meet them, then just sit at a table in a restaurant next to them and notice their mannerisms, hear the tone of their voice and, of course, see what they look like. I have heard many stories of children connecting with their birth parents; some meetings were good, and some were not so good, and some proved to be downright sad.

My birth mother was pregnant with me beginning in late March or early April 1956. Sixty-three years later, I had no interest in barging into her or my birth father’s life uninvited, risking collateral damage for them, and saying, “Surprise! Look at me! Guess who I am!”

My birth mother was pregnant with me beginning in late March or early April 1956. Sixty-three years later, I had no interest in barging into her or my birth father’s life uninvited, risking collateral damage for them, and saying, “Surprise! Look at me! Guess who I am!”

Yet, with the constant encouragement of a special “friend,” who bought me the DNA kits for both 23andMe and Ancestry.com, we opened the door to finding a DNA match with a second cousin and then, scouring her family’s engagement and marriage announcements, and her family’s obituaries, coupled with the help of the 16th Circuit Court of Jackson County, Mo., opening my adoption files after I petitioned them, I found the name, address and telephone number of my soon-to-be 90-year-old birth mother.

With additional help and encouragement from Diane McCullough, who is more my dear friend than cousin and who brought her investigative skills to bear, we learned that my birth mother lives independently in senior apartments, walks with her walker, goes to her Presbyterian church every Sunday if she can find a ride, never married, and never had any other children.

I can’t describe the cavalcade of emotions I experienced over the next couple of weeks. You name it, I experienced it.

“After asking a multitude of people what I should do, I decided to write my mother a letter.”

After asking a multitude of people what I should do, I decided to write my mother a letter. My feeling was that even if she didn’t want to meet or to have any contact with me — which I would desire — I could at the very least provide her with some answers that I believe a birth mother might have about a child she gave up for adoption so many decades ago.

Here is the letter I wrote my birth mother. I wrote and edited the letter under a waterfall of tears and before sending it and added photographs of me, my children and my grandchildren and my original birth certificate with L’s name on it.

The first letter

Dear Lillian,

I hope this letter finds you in good health and spirits!

I have thought of a thousand ways to say this to you, and I simply don’t know of another way to say it, except to say that it is my belief you gave birth to me on January 14, 1957, at the Willows Maternity Sanitarium, Kansas City, Mo.

I located you with the help of the 16th Circuit Court, Kansas City, Mo., who provided me not only my live birth certificate with your name on it, but also a five-page interview you did with your Willows’ case worker.

We haven’t communicated, but I was a DNA match with your niece, on Ancestry. After finding out her name, I searched her family’s engagement announcements and obituaries. Through your sister’s obituary, I found your current location.

“I want you to know up front, if you don’t want any further contact with me, I will respect your wishes and I will harbor no ill will toward you.”

At this point you are probably shocked. I don’t know if you ever thought this day would happen or if you wished this day would never happen. I want you to know up front, if you don’t want any further contact with me, I will respect your wishes and I will harbor no ill will toward you.

I cannot begin to understand what it must have been like for you to become pregnant, without a husband, in 1957. What I do know is what you did with the choice you made in carrying me, caring for me, during your pregnancy by yourself — even though your sister helped you, I believe — was a heroic, brave and unselfish choice. For that, I can only say, “THANK YOU!” There is no way to put into words just how grateful I am for the things you must have endured physically and emotionally to give me life.

I was adopted by a wonderful couple who loved and took care of me in Independence, Mo. Ironically enough, they were born and raised in Pleasanton, Kan., and they retired back to Pleasanton. I know your brother also lived in Pleasanton, but I have no way of knowing if they knew one another. I do know, from an obituary that he worked for a distant cousin of mine for a while.

Both of my adopted parents are deceased now, but at the age of 4 they told me I was adopted and that a “courageous, loving woman, who had to make a very difficult choice” birthed me and that I was lucky because I “now had two mothers.”

We remembered, honored, and celebrated you on Mother’s Days. We prayed for you while I was growing up, and I pray for you even now.

The author’s grandchildren

I apologize if this is too much information as I have no way of knowing what you are making of this unexpected invasion into your life. I will simply say that I have had a great life. I am a chaplain and I earned a bachelor of science degree from the University of Tulsa, Tulsa and a master of divinity degree from Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, Kansas City.

Besides Independence, I have lived in Tulsa, Chattanooga, Atlanta and now Paducah.

My late wife, Brenda, to whom I was married almost 34 years, who died from complications from a stem cell transplant two-and-a-half years ago at the age of 57, and I had three children, Hunter, Brooke and Megan. All three graduated from the University of Louisville, and they all three live in Louisville.

I have gone way too far, so I will leave it here, for now. If it is your pleasure, I would like for us to have further conversations and/or correspondence. If you would like to do so, my cell number, address and email are located at the top of the first page.

I have dreamed about meeting you my entire life. I have told people for decades how I would like to know what my mother looks like, what she sounds like, and myriads of other things about you. There are physical characteristics that my children and their children possess that do not look like me or my late wife or her side of the family, so we have always said, “That must be from my mother’s side of the family.”

If nothing else, please know and never doubt for a second, my family and I are so very, very grateful for you!

The response

I was pulling out of a Paducah gas station one night, not far from my house, and my cell phone rang. I glanced down at the caller ID, and my whole body clenched. The caller ID said it was Lillian.

FINALLY!

I picked up the phone, answered and said as pleasantly and as clearly as I could muster, “Hello. This is Tom.”

The female voice on the other end said, “Do you know who this is?” I hesitated even though I thought I knew who it was on the other end as I had placed Lillian’s possible phone numbers in a contact titled Lillian. It could have possibly been one of her friends or a family member, so I said, “No. Who is this?”

“Then she said, very matter of fact, ‘This is the woman who you think is your mother.’”

My hand was shaking, my lips quivering, as I held my phone close to my ear, waiting, wanting, for what I had waited and wanted my whole life to hear and then she said, very matter of fact, “This is the woman who you think is your mother.”

We talked for three hours and 12 minutes. We talked about everything.

I was in shock and amazement, wrapped in eternal gratitude. I tried to assimilate, deconstruct, recollect and take notes of all the stories told, words said, emotions conveyed.

It was all good, and we made plans to stay in contact.

On the road for the visit

I wrote this next portion from a hotel room in Hays, Kan. Why there? Because over the past six months, my birth mother and I have talked two times each week, an hour and a half at a time, and we email almost every day.

Her name is Lillian (pronounced lay-yan). We are slowly, consistently building a mother-son relationship. Things are good with us.

She is 90 years old, living independently in Longmont, Colo., in a one-bedroom apartment where she has lived for 25-years. Her body is starting to betray her. She is in almost constant pain due to the twin-headed monster of osteoarthritis and osteoporosis.

A month earlier, we began exploring the possibility of me coming to Colorado for a visit, even in the middle of a pandemic, and that is why I am spending the night in western Kansas.

I am fortunate to have had multiple mothers. Delyte, my mom, the mother I have known all my life, was a delight. My great aunt Lorene, who is 101, also helped mother me from two doors up the street. I have had many women who invested their love into my world in maternal ways.

“Tonight, I am trying to write through the windshield of my heart.”

Tonight, I am trying to write through the windshield of my heart. To anticipate what these next few days will bring in Colorado with a mother I have never met leaves me with more than a little anxiety. Things are really good electronically, but that is different than living in the same space.

Today has been a juxtaposition of emotions. I drove 685 miles on this Sunday. I passed through Columbia, Mo., home of my favorite childhood college, the University of Missouri. The panorama of memories was spurred by exits off I-70 that led to fields and gyms where I played, the Independence Center Mall where I went on my first date, the exit for Sterling Road, which leads to my childhood home, Kauffman Stadium and Arrowhead Stadium popping up on my left, the Fellowship of Christian Athletes headquarters on the right, and then a multitude of familiar landmarks as I snaked my way through Kansas City.

I am excited and anxious as I think of the 365 miles that stand between me tonight and meeting my mother tomorrow afternoon.

Traveling with our history

My eyes opened on Monday morning, and my first thought was, “Time to get out of Dodge.” Almost instantly, I realized I was indeed in a western Kansas town, but it wasn’t Dodge City, it was Hays. I pointed my rental car west on I-70 with each roll of my tires carrying me closer to writing a chapter of my life that was always there, but that held nothing but blank pages.

“We all are accompanied by our histories, wherever we go.”

I didn’t travel in a vacuum. I hadn’t the day before, either. We never do. We all are accompanied by our histories, wherever we go.

The day before, the interstate exits for my hometown of Independence and Kansas City, held large chunks of my life that are now neatly tucked away in the treasure chest in my heart. Hysterically, the exit for Topeka, Kan., brought me to uncontrollable laughter. In 1965, ironically, inexplicably, I won my age group at the Mid-America Accordion Festival, in Topeka. It was ironic because I hated playing the accordion, and I was and am tone deaf and rhythmically challenged.

Maybe it was because God has a wicked sense of humor or — as my friend Dwight Jackson once observed — maybe I was so pathetic it was a “sympathy” vote. Whatever, on that day, I played that squeeze box in such a way that after playing I Wish I Was Single, Again and On Top of Old Smokey, that I went home with the first-place trophy. It was also the last time I played an accordion. A bat, a glove, a baseball and basketball became worthy replacements.

The Manhattan exit reminded me of a Louisville/K-State football game where my son, Hunter, filled in for the starting quarterback and led the nationally ranked Cards to a victory in front of 51 of our friends and family.

The Salina exit reminded me of my oldest friend, Larry Wayman, who left Three Trails Elementary, where we attended, when his father took a job in Salina. That summer my parents placed me, by myself, on a Greyhound Bus, bound for Salina, to visit Larry when I was 12 years old. Seriously, what were they thinking?

I was flanked on both sides of I-70 by heads of milo, ripe for harvest, thousands, yes thousands of giant wind turbines, and miles upon miles of flat prairies.

When I spotted the exit sign for Goodland, Kan., I remembered a youth group I was “leading” home from a Colorado ski trip when we had to spend the night at the Methodist church there because of a western Kansas snowstorm. In case you’re wondering, I called the local Baptist church, but there was no room at the Baptist church because another youth group had already beaten us there.

Limon, Colo.? I will refer you back to the story of Goodland, but this time it happened on two different trips, and unbelievably, at the same truck stop.

All the while, my anxiety was spiking, and I wondered if I was tempting fate in meeting my birth mother. I wondered if this was some sort of self-indulgent quest. I was stressed.

Finally to Longmont

Finally to Longmont

As I approached Denver, I chose not to take the bypass to Longmont, where Lillian lives, but instead to go through Denver where I had not visited since the late 1990s. Just north of Denver, I put Lillian’s address into my GPS.

It was 1:30 p.m., exactly when I had told her I would arrive. Finally, there it was, my destination, where on the third floor lived the woman who gave me life, who jump-started everything that became my story.

I found a space to park in front, on the street. She was watching from her third-story apartment, she told me later.

I gathered myself, took some deep breaths, brushed my hair — I know, but who wants their mother to see her son for the first time with messy hair?

I got out and walked toward the front door of the apartment complex where Lillian lives. Inside the mini lobby was a security system where on a box on the wall, you have to call the resident for them to buzz you in. There was some confusion on my part about the logistics. I waited for the door to click, signifying that I was free to walk in and meet my birth mother.

I waited. I waited some more. No click on the door. I waited. Then, a hunched-over, sub-five foot (formerly 5’6″), sub-90 lbs., raven-red haired, blue-eyed, woman was standing on the other side of the glass door, wearing shorts that — even though I am not a fashionista — had to be two sizes too large. Our eyes met as she struggled to open the door. She smiled. I smiled. I grabbed the door and walked through to a time that typically would have happened six decades ago.

I waited. I waited some more. No click on the door. I waited. Then, a hunched-over, sub-five foot (formerly 5’6″), sub-90 lbs., raven-red haired, blue-eyed, woman was standing on the other side of the glass door, wearing shorts that — even though I am not a fashionista — had to be two sizes too large. Our eyes met as she struggled to open the door. She smiled. I smiled. I grabbed the door and walked through to a time that typically would have happened six decades ago.

Lillian rode the elevator up to the third floor without the help of her walker or cane. I was walking behind her, hoping I could catch her if she tripped. Our roles were irretrievably reversed. A mother always wants to protect her children until the day they die. Here, I was protecting the one who had protected me, unconventionally, by giving me away at birth.

We got off the elevator, turned left, and immediately turned left into her apartment. Her one-bedroom apartment was as I had been told by her; it consisted of a tiny galley kitchen on the right, a short hallway that took you to the pantry, bathroom, closet and the bedroom, while the living room was straight ahead. The apartment, as I had been apprised, was cluttered and needed some TLC. There was work to be done. That was one of the reasons I drove to Longmont.

Getting to know you

We made our way to her couch. She sat down on the far right side. I pulled a chair in front of her to talk to her face-to-face. She smiled and patted the couch with her left hand, indicating she wanted me to sit next to her. I did as she asked. We hadn’t talked long until her left hand reached for my right hand while my right hand was reaching for her left hand. They met. The mother’s hand and the son’s hand clasped for the very first time. The broken circle was now closed.

“The mother’s hand and the son’s hand clasped for the very first time. The broken circle was now closed.”

We talked about my trip. She apologized for the state of affairs of her apartment. I told her not to worry about it. We made lists of things we wanted to accomplish while I was there. She apologized for the 13 bags of trash held in Walmart plastic bags. We talked about nothing. We talked about everything. Time passed silently in our hearts. I took the trash down to a chute at the end of her hallway while she led the way.

Afternoon gave way to dusk, and we both said we were hungry. She loves the pizza from a joint called Blackjack Pizza. I got up to go pick it up. She deliberately, gingerly, got off the couch. I stood close in case she fell. As she raised up, her two-sizes-too-large shorts went down. Way down. All the way to her ankles. Awkward! I turned away. She laughed and said, “There’s an image you didn’t need.” She did what she needed to do to become proper. I was certain this moment would be edited out of the Hallmark Channel movie about us meeting.

I left and brought back the pizza. I prayed for us, and then we ate pizza on her couch and watched Monday Night Football, where the Denver Broncos were playing the Tennessee Titans. I do love the fact that Lillian loves football, especially the Kansas City Chiefs. The pizza tasted good, then it was gone, in the same way the Broncos chances were gone against the Titans.

I was exhausted in every way a human could be exhausted. We said good night, and I left to drive back to my hotel room.

I was exhausted in every way a human could be exhausted. We said good night, and I left to drive back to my hotel room.

It was an emotional six-mile drive. I was trying to remember everything that was said and what wasn’t said. I attempted to place my tsunami of emotions in some kind of orderly list. I wasn’t successful. It was good, but it was cloudy. It was new.

There was too much to effectively process. I didn’t care what it all meant. That was the wrong question to ask, so I rode to the hotel in the fog of a dream come true.

The second day

I awoke Tuesday morning in my Best Western suite (Thanks, Priceline!). Seriously, one person in a suite is as useless as, well, you know.

I am attempting to become more open to whatever the Spirit, the Universe, whatever you want to call it, is bringing my way. If you have tried this, it is easier said than done. I am open, but the reality is I was open, not expecting, a wall of uncertainty today.

Lillian, like many senior, senior citizens, doesn’t go to bed until after midnight, like 3:00 or 4:00 in the morning, which pushes her wake-up time to sometime between 11 a.m. and noon. This gave me a free block of time to get my walk in and run some errands for her.

My hotel was in a business park, off an I-25 access road, so there wasn’t an ideal spot to walk. I decided to just lap the business park a few times. I made another executive decision to wear my Kansas City Chiefs’ hat, especially after a Denver Broncos’ loss. A person has to have priorities.

My hotel was in a business park, off an I-25 access road, so there wasn’t an ideal spot to walk. I decided to just lap the business park a few times. I made another executive decision to wear my Kansas City Chiefs’ hat, especially after a Denver Broncos’ loss. A person has to have priorities.

My Apple watch told me I got my miles in, but my mind and heart were occupied with the events of yesterday and the promise of what today held. A lot had happened in the last 21 hours for me, for Lillian, for us, for my family.

I tried to calm my mind as the onslaught of questions continued to invade my neat and tidy world of need-to-know. I don’t know about you, it may just be me, but I like my mind and heart to be orderly, where all my emotions are dusted and placed just right, for all to see.

I finished my walk, but not the storm in my heart and mind. I took a shower, dressed and ran some errands in terms of picking up some items that means nothing for someone who is mobile, like me, but for someone who is not, is monumental. It did not escape me that besides sending Lillian some little things via Amazon, this son had done none of the normal things a son does for his aging mother.

As odd as it felt, it also felt right. I knew there was no way to recreate a normal — whatever normal is in family life these days —mother-son history, but I simply wanted to help out in whatever way I could.

I finished the errands and arrived back at Lillian’s apartment. I set up the new landline phone she had wanted from Best Buy and a toaster from Walmart. I found out toasters during the pandemic are in high demand and short supply — everywhere — who knew?

The author’s maternal grandparents.

While I was checking off my list of things to do, Lillian pulled out pictures and the accompanying histories of my blood family. It was startling to see some physical similarities and to uncover a family that was there all of my life but completely out of sight.

A mother-son outing

We had talked over the phone that if one day Lillian felt good enough, I would put her in a wheelchair I borrowed here from a friend and take her out of her apartment. We laughingly referred to it as, “The Great Escape.” Getting out of her apartment, even pre-pandemic, was not a usual event for her. In 2019, she had spent more than a third of the year in a hospital or a skilled nursing facility. She came back home in September 2019, and she thinks she has only been out of her apartment four or five times since then.

Mother said she didn’t feel great, but she did feel good enough to get out. So we ordered her groceries online and set a time to pick them up. She didn’t like the idea, at all, of getting in a wheelchair. Like most of us, the idea of being dependent on someone or something doesn’t sit well. She pleaded her case to me, unsuccessfully, that she could make it with her walker. I provided the dissenting opinion.

I told her I had the physical ability to pick her up, throw her over my shoulder, and carry her to the car before I would let her shakily go with her walker. At that point, I took on the role of benevolent dictator, for better or worse. She didn’t like it, but she reluctantly slipped into the wheelchair. With that, we moved into a world she was increasingly becoming unfamiliar with and one you and I take for granted, every swinging day.

As I wheeled her out of the apartment building into the Colorado sunshine and air, her head started moving from side to side, taking in what had once been familiar and now seemed fresh and shiny.

We made it to my rental car, a 2019 Nissan Altima, and she seemingly bounced from the wheelchair into the car. “Bounced” might be a bit of hyperbole, but “bounced” works for me.

Because of the combination of her diminutive status and the unthinkable fact that the Altima’s passenger seat had no way to raise it, Lillian was only able to see out the windshield at a greatly diminished angle. Here’s the place in the story where I could have heroically reached into the back seat and picked up the two pillows I brought so she could sit on them and see out the windshield like the rest of us, but I didn’t. Complete unawareness to the solution of the problem sitting right behind me. It didn’t come to me during our 42-minute wait for her Walmart groceries. We laughed about it later, but I think I blew any chance at winning the award for the “2020 Son of the Year.”

Because of the combination of her diminutive status and the unthinkable fact that the Altima’s passenger seat had no way to raise it, Lillian was only able to see out the windshield at a greatly diminished angle. Here’s the place in the story where I could have heroically reached into the back seat and picked up the two pillows I brought so she could sit on them and see out the windshield like the rest of us, but I didn’t. Complete unawareness to the solution of the problem sitting right behind me. It didn’t come to me during our 42-minute wait for her Walmart groceries. We laughed about it later, but I think I blew any chance at winning the award for the “2020 Son of the Year.”

The groceries finally arrived. The plans were to head north to Estes Park, nestled in the Rockies, about 50 minutes away. The setting sun was working against us, so we defaulted to Plan B and headed 16 miles southwest of us, to Boulder.

Seeing all things new

Lillian was still only seeing tall things, but she was Chatty Cathy, describing how her town and the region had changed in the two years since she last appeared from her apartment. She spoke of new growth, a couple of places where she had worked, where people had once lived, and how she lived so close to the Rockies but hadn’t seen them from within the captivity of her apartment.

I had not been to Boulder since 1997, and it has exploded. We drove around the University of Colorado campus, which is breathtaking, tucked next to the Rockies.

We saw what we wanted to see and turned back toward Longmont. We went through a Burger King drive-through, because, as she said, “It’s been a long time since I’ve had a good hamburger.” For me, it has been a long time since I had seen the world through the eyes of someone who was seeing all things new.

“Sitting next to my birth mother, who was as excited as a prison escapee, (this day) was extraordinary in its ordinariness.”

On the surface it would seem to someone on the outside looking in, to have been an ordinary day. Sitting next to my birth mother, who was as excited as a prison escapee, it was extraordinary in its ordinariness.

Seeking medical help — on a short timeline

I had reminded her the night before that she had indicated that Wednesday would be the day she would abdicate her independence, see some medical professionals. Mother is fiercely proud to be independent, and like most of us who are naive enough to believe ourselves to be independent, to a fault.

She said she needed to call by 8 a.m. to get an appointment, and she was never up by 8 so she would have to go another day. I gave her the look a mother gives her teenage son on why he wasn’t home by curfew. I told her I was entirely capable of calling and making her an appointment. She reluctantly gave me the phone number, we said goodnight, and I drove back to my hotel room.

On Wednesday morning — the last full day of my visit — I called the clinic at 8 a.m. A machine answered. I pushed 1, then I pushed 3, pushed 1 after that, before a human voice answered long enough to say, “Will you hold?” I was on hold before I could answer. Finally, almost 10 minutes later, a female voice informed me it would be impossible to see mother today. My stomach hurt. I immediately went into full-blown evangelist or lawyer mode, as I pleaded my case, more than my case, her case, about my limited time in getting her to the clinic on that day and that day only.

Whether I persuaded the scheduler or whether she just wanted me to shut up, she told me an 11:20 had miraculously become available.

I thanked her, hung up and called Mother to wake her up. I wasn’t looking forward to that. Mother told me it was an impossibility for her to be ready in time. I told her I would see her in 45 minutes, and I hung up. When I walked into her apartment, she was sitting on her couch, legs crossed, her face was exasperated, and she was holding a piece of paper that, in handwriting, read, “Your 11:20 appointment today has been cancelled.” Seems the clinic had called the manager’s office, instead of Lillian.

I called the clinic, went through “Press This Number Bingo,” and I was finally told by an anonymous voice that the doctor had a family emergency and she had to cancel all her appointments for the day, there were no other openings with other doctors, and going to the emergency room was not only our best, but it was our only option.

Mother was trying to act disappointed in the recent turn of events, but she is not a good actress. I remembered seeing a University of Colorado urgent care a couple of miles away. So, mother stubbornly got in the wheelchair, and off we went.

The doctor at the urgent care, after a 20-minute consult, encouraged us to go to the hospital. If I had a nickel for every time I heard on the way to the hospital emergency room, “I don’t need to see a doctor. I’ve lived this long.”

The emergency room

I will give you the highlights or lowlights of our seven-and-a-half-hour visit at the University of Colorado Hospital Longs Peak. Mother’s CT scan showed not one, not two, but five broken ribs from a fall she had two-and-a-half weeks earlier. I asked for a social worker consult and, as a result, we were able to set her up with a home health nurse, physical and occupational therapy — which she desperately needs.

I told her before the physical therapist came into her room in the ER for a consult that the main thing he would look for would be how she got out of and back into bed. She gave me a quizzical look and I told her it was a benchmark on whether they believed she could continue to live by herself.

“When the physical therapist asked her to get out of her bed and go to her walker, she lost 30 years and bounded out of the bed.”

When the physical therapist asked her to get out of her bed and go to her walker, she lost 30 years and bounded out of the bed, strode down the hall and back with her walker and climbed back into bed with a sly smile of satisfaction.

The PT seemed satisfied and left. She turned to me with a sheer look of exhaustion and said, “I thought that was going to kill me!” I exploded into laughter, and she just shook her head side-to-side proud of her turning the clock back.

Meds were updated and prescriptions filled. They discharged her, and we headed toward a previously agreed upon dinner of Kentucky Fried Chicken. We went through the Colonel’s drive-through and headed back to her apartment.

How do you say goodbye?

If there were a video of it, that is what you would have seen. What you wouldn’t have seen was a son and a mother knowing that their first visit was approaching its end. How do you say goodbye? Who would want to? How could we say goodbye after 63 years of never having said hello?

“How could we say goodbye after 63 years of never having said hello?”

We finished reviewing her doctor’s visits and chit-chatted in between bites of Original Recipe. I finished first and nervously did some final tidying up around her apartment. I did what I could. I didn’t think it was enough. I went back to the couch and sat down next to the reason for my existence.

My breathing, was I breathing? How could I say goodbye? I love words. This night, emotions were scattered and smothered, and words were scarce.

I mustered enough courage to turn to her. The look on her face told me she knew it was time. My mind went blank. My heart pounded. My fingers were intertwined with her gnarled ones. I whispered to her, “Would you like me to pray for us?” She nodded and closed her eyes. I prayed. I prayed for her health. I thanked God for the visit. I prayed in the usual way. I tried to catch my breath. I prayed some more, but I don’t remember exactly what.

“Her arthritic fingers gripped my fingers harder, begging me not to go.”

Her arthritic fingers gripped my fingers harder, begging me not to go. She asked me if I was coming back in the morning before I left. She already knew the answer. I was heading east, at daylight. Mother looked despondent. I felt like a traitor.

I stood up in front of her. I was a prisoner of the moment. With our fingers still clasped, I gazed into the eyes I never thought I would see. I told her: “I love you, Mother. Thank you for delivering me. Thank you for responding to my letter. Thank you for letting me visit you. Thank you for loving me. Thank you for accepting me. Thank you for telling me you love me. Thank you for being you. My God, you have made my dream come true!”

Our fingers released our grasp. I walked to the door without looking back. As my hand turned the doorknob, I heard: “Son? Thank you! I love you!” I looked back and instinctively responded, “I love you, too, Mother!”

I was so hopeful, expectant about finally meeting her, I had somehow forgotten that movies have to have an ending, even if until the premiere of the sequel. How do I live with this ending? How does she? Is it an ending or a doorway into the next episode?

Driving back to the hotel and away from my mother seemed counterintuitive. What son doesn’t need his mother? What son drives away from his mother when she desperately needs his help after he has spent most of his life wanting to connect with her?

The stable of answers to these questions ranged from the logistics from our distance apart to trying to corral what just happened in the past three days of being together and the previous six months of phone calls or emails.

“Finding its way through my emotional chaos, a calm pried open the door to my soul.”

My emotional fuel tank showed 0 miles left. My mind was spinning. Finding its way through my emotional chaos, a calm pried open the door to my soul. The calm may have been sent by God or not. I don’t know. I don’t care. The calm allowed me to understand my great quest was finished. Of course, there is more to learn, but the unknown variables that made my heart restless were answered.

The answer was there all the time. It always has been there, hiding in plain sight. The answer is not adorned in confetti or flowers or accompanied by a marching band. The simplest, profound answers always stand alone.

My quest is to simply love her. To love her the best I can, as long as I can. I mean, isn’t that what a son does for his mother?

Tom Cantwell is a graduate of Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary and a chaplain in Paducah, Ky.

Finally to Longmont

Finally to Longmont