The pandemic has changed us. At a minimum, the last 15 months have awakened us to our vulnerabilities. So as the post-pandemic world begins to peek over the horizon, we’ve also become painfully aware of the deepening and widening division within our communities of faith as well as our country as a whole. Many of us now hunger for wise insights and redemptive actions for this new day bolstered by a highly relevant theology. What voices might assist us?

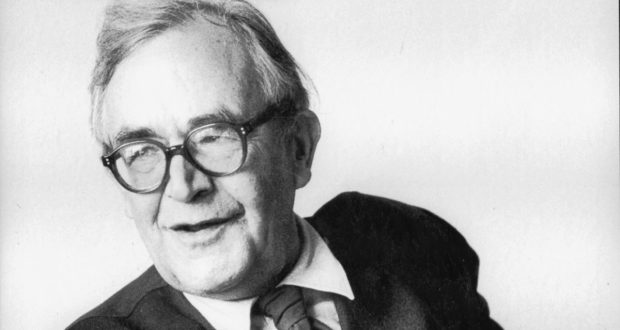

Karl Barth had a lot to say in has time. He still does. Reading his vastly intimidating four-volume Dogmatics is not for the faint of heart. But it turns out, his many words contain vital wisdom for our time.

David Jordan

Barth already was being rediscovered. At the beginning of our new millennium, his prophetic voice cracked through the perilous openings of our then-titillating postmodern world context. Now, however, with the new looming challenges for the church, Barth’s words become especially pertinent.

Barth, you see, constantly found himself revising and revisiting his theological underpinnings. Perhaps more than any theologian of the last 200 years, Barth faced a world consistently in turmoil. His theology began to evolve early. And it consistently centered upon the mystery of God.

The mystery of God as prophetic voice. Barth began his ministry as a Swiss Reformed pastor in the village of Safenwil, Switzerland (1911-1921). He gained a deep love for and concern about the workers of his area. Their poor labor conditions and lack of adequate health care generated a number of sermons aimed at the owners of the mills where they worked. The owners weren’t happy. Swiss Reformed pastors were supposed to maintain the status quo and keep the powerful happy by keeping the laborers acquiescent.

In protest for what rich folks viewed as “political” sermons, five of his six parish leaders quit. They accused Barth of being a socialist. Maybe he was. The term was used as a general putdown then just as it is now. But socialist or not, he was definitely a prophet. He was concerned about the people of God; he was passionate about the justice of God. And he knew the church had fallen short on its sacred obligation. He exemplified the biblical definition of prophecy: speaking truth to power.

“Swiss Reformed pastors were supposed to maintain the status quo and keep the powerful happy by keeping the laborers acquiescent.”

For the next 50 years, Barth contributed keen insights, devoted himself to biblical preaching and teaching, and remained fervent in his cultivation of the next generation of prophetic voices.

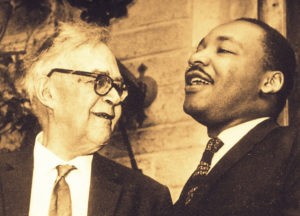

The mystery of God through generational crises. God’s presence and Barth’s passionate expression of it addressed countless crises. In roughly the order he faced them: World War I and the militaristic and cultural co-opted-ness of German friends, colleagues and mentors; the Weimar Republic’s decline and decadence; colonialism and widespread white supremacy; economic crises with comingling hunger, homelessness, divisiveness and social angst; the rise and spread of Nazism, World War II, followed by the horrors and devastation of much of Europe; post-war existentialism, nihilism, socialism and communism; the arms race, the atomic era with multiple threats and widespread mistrust; the Korean Conflict; race riots, Vietnam, and the seemingly endless dysfunction of the institutional church, both Catholic and Protestant.

Karl Barth with Martin Luther King Jr.

The critique of the church. He remained an equal-opportunity ecclesiastical critic throughout his life. “What we need,” he said in 1963, “is an energetic de-sacrementalizing of the church.” As the Lutheran bishop of Bavaria, Hans Meiser, once said of Barth during his early years in Germany: “One cannot build the church with Karl Barth.”

And while many found that to be true, many more found Barth’s deep concerns and well-worded critiques to be spot on. They were then; they are now. Ultimately, the witness to God’s work in the world and in the community of faith was at stake.

The mystery of God at the center of the circle. At the heart of Barth’s theology lies an empty circle reserved for the unfathomable mystery of God. The presence of God, the mystery of God, the reality of God fills and shines at the center. This circle, then, is surrounded in a spokeless wheel. And around the circumference of that wheel Barth envisions the people of God standing side by side (by this, he means all people, regardless of race or place or religion). His justification: “Because the humanity of Jesus Christ is the sacrament of the living God, all human life takes on a sacramental quality.” All people, everywhere.

His vision is telling. All of us, together, regardless of our race, creed, nationality, faith or perspectives are gathered around the circle, this spokeless wheel with God at the center. As each of us works within our own theological system and with our own God-given abilities for theological insight, we move from our places on the spokeless outer wheel toward the center of the circle, or in the direction of God’s mysterious presence.

“This model negates any potential for white supremacy, colonialism, imperialistic desires or cultural superiority.”

The critique of cultural or racial superiority: Crucially for Barth, and now especially for us, the closer we move toward the center, the closer we move to one another — whether we like it or not. This model negates any potential for white supremacy, colonialism, imperialistic desires or cultural superiority. In fact, in Barth’s ongoing critique, each of these along with other perspectives that would negate God’s good creation and the human community would move those individuals away from God and beyond the circle, ostensibly into outer darkness.

The mystery of God as a bird in flight. Further, the mystery of God is “never ‘caged bird’ but always a ‘bird in flight.’” Eberhard Busch, Barth’s friend, assistant and biographer, quotes him with the same “caged-bird” imagery saying: “the whole church business could make one sick and that one could exist in it only like a bird in a cage which keeps on bumping into the cage’s bars every time it wants to fly freely.”

The critique of shallow theology: Our post-pandemic world can use a little Barth in this area as well. While offering constant critique, his frustration with the institutional church parallels our own time. Pastors and congregants alike are heard once again questioning traditions, rituals and long-held “essentials” that possibly have been contributing to our own caged-bird experiences. (Paradoxically, we’re tempted to cling to traditions in the post-pandemic era just so we can reclaim a sense of normalcy). Many further share in the concern that God’s Spirit has indeed been so institutionalized, Barth’s cage critique rings as true now as it did then.

“How do we respect the mystery of God while attempting to provide larger crowds, better offerings and institutional sustainability?”

Churches and denominational headquarters scramble to figure this out. How do we respect the mystery of God while attempting to provide larger crowds, better offerings and institutional sustainability? Most pastors today are inundated with website gimmicks, capital campaign secrets, catchy slogans, irresistible music ideas, innovative sound systems and revolutionary software. All this usually comes with no theological underpinning or concern for better biblical foundations.

As a theologian, Barth sensed in his day what remains true now. Pastors as well as parishioners crave a more meaningful intersection of Spirit, church and theological understanding. Our beloved communities wish for us pastors to be afire with substantive Truth that will cultivate in the people of God biblical lessons and a life-giving gospel.

The mystery of God in community. Finally, his advice to get us all to that better place is instructive. In Barth’s “Forms of Ministry,” preaching and teaching rank high (second and third) on his list of essentials. But his first priority for the people of God is surprising.

Barth was a great lover of music. He composed his lessons, theological treaties and sermons every day while listening to Mozart. And for him, music in the community of believers conveys far beyond the sum of its parts. Singing especially, or what he simply defines in his “Forms of Ministry” as “praise,” provides the structure, theology and joy so necessary for then and now.

Praise: Let everything that has breath praise the Lord! (Psalm 150). For Barth, “singing is the highest form of expression.” It is not only an expression of gratitude and a way to give honor and glory to God, it is also a valuable indicator of a church’s clarity of purpose. Indeed, a church that cannot sing well and joyfully is at best “only a troubled community which is not sure of its cause and of whose ministry and witness there can be no great expectation.” Ouch. Especially following more than a year when singing was discouraged, we are challenged anew by his harsh, but unsettlingly true reminder.

“For him, music in the community of believers conveys far beyond the sum of its parts.”

Preaching: “It proclaims, summons, invites and commands … It calls each and all to decision for faith instead of unbelief, to obedience instead of disobedience, to knowledge in the battle against ignorance.” As Barth stood before his students in the Bonn University ruins following the horrors of the Second World War, he declared:

Proclaim the gospel to all creation! The church runs like a herald who has a message to deliver. It is not a snail that carries its house on its back and feels so comfortable in it that it only sticks out its feelers now and again and then thinks that it has adequately carried out its public duties. No, the church lives from its commission as herald. It is la compagnie de Dieu, the company of God.

Poor preacher, and “poor community whose ministry is deficient in this basic form!”

Teaching: “Destruction of the identity and breaking of the constancy of the content of the community will necessarily result where the community is slack in the vigilance continually demanded of it and in its further instruction in the school of its Lord.” If we do not know what we believe and even more specifically, what the Bible says, then how can we remain spiritually and intellectually confident in the face of “the dominant philosophy of the age”? Therefore, “Christians have both the right and the duty to inform themselves.” Once again, poor preacher, and poor community if we are deficient in this vital source for a learning community. The very definition of “disciple” means in its most basic form, learner. Together, our teaching and learning must span a lifetime of seeking to follow Jesus better by learning together how, why and for what reasons.

Once it is safe again to sing, let us do so with gusto. Offering praise for a new day and a grace that transforms us all changes the world around us. As we move past the pandemic into a new horizon of unknown opportunities and tensions, let us preach with passion and fervor continually undergirded by a deep, biblical understanding. And let us teach, learn and apply new insights to a constantly changing world as disciples of Jesus.

Barth still speaks. And we, the people of God, still must hear, respond and pass along his love of God, his passion for the Bible and his consistent desire to boldly, joyfully disseminate God’s mysterious, saving grace to all the world.

David Jordan serves as senior pastor of First Baptist Church of Decatur, Ga.