Every disconnection from communal wholeness goes back to a disconnection within the self, which is fundamentally experienced in bodies. So the way Christians talk about Jesus being born as a human body has the potential to shape either wholeness or disconnection from self and neighbor.

Perhaps no other community has been hurt by this theology fueled disconnection more than intersex people.

Intersex people have bodies that are different from the male and female bodies most of us are accustomed to having. Some intersex people may have genitals that are typical of both male and female bodies, including having both ovarian and testicular tissues simultaneously. Others may have chromosomes that are different from what would be expected for their physical appearance and may never know they are intersex.

While many people have not considered this reality, intersex bodies are common in a variety of species.

Because all theology is ultimately an exercise of faith, it lives within a spectrum ranging from speculation to interpretation. But whether our theology is accurate or not is beside the point. What matters is that the way Christians talk about theology, especially regarding the incarnation of God being born in the body of Jesus, affects the communal wholeness of intersex people.

The incarnation as reaction to brokenness

Conservative evangelicals have been shaped by a cosmo-theological narrative of Creation, Fall, Redemption and Restoration. They believe God created everything perfectly whole, but that sin entered the world and brought brokenness, especially experienced in human bodies and sexuality. Then they believe Jesus came as a reaction to our brokenness to redeem some of our souls and that he eventually will return again to restore Christian bodies back to original perfection.

“This narrative frames the incarnation of Jesus as a reaction to brokenness and frames the identities of our bodies and sexuality as broken.”

Besides its obvious disconnections from evolutionary reality, this narrative frames the incarnation of Jesus as a reaction to brokenness and frames the identities of our bodies and sexuality as broken. And this is why so many believe LGBTQ people, as well as intersex people, are manifestations of brokenness.

In an article at The Gospel Coaltion, Denny Burk called intersex people a “morally confounding situation,” an “ethical challenge,” and a “problem.” Rather than offering any helpful thoughts, Burk responded by lamenting progressive and liberal Christians committing a “sustained assault on what the Bible teaches about gender and sexuality” in a “Bible-ignoring zeitgeist.”

In other words, the net result of The Gospel Coalition’s response to intersex people is universal disconnection.

The incarnation as overflowing love

But there is another view of the incarnation that is older than evangelicalism. Denis Edwards, who was a priest as well as a professor for The Catholic Theological College, notes: “In one view, the incarnation is thought to have been caused as a remedy for human sin. In the other, associated with Franciscan theology, particularly Duns Scotus (c. 1266-1308), God’s plan of creation always had the incarnation of Christ as its center.” Or as the modern Franciscan friar Richard Rohr says in The Universal Christ, “God loves things by becoming them.”

“When we see intersex people in light of an incarnation of overflowing love, we no longer experience brokenness, but infinite wholeness.”

To frame the incarnation as God’s becoming human in overflowing love is to affirm the goodness of human bodies and sexuality and the fulness of God experienced in them. And thus, when we see intersex people in light of an incarnation of overflowing love, we no longer experience brokenness, but infinite wholeness.

The incarnation as the intersex body of God

Conservative evangelicals believe gender and sexually binary distinctions are rooted in creation itself, which is a reflection of a distinct God. They often will go so far as to demand that all members of the Trinity be referred to with exclusively he/him pronouns.

But if conservative evangelicals would be consistent in their literal interpretation of the Bible, they would discover in Jesus the intersex body of God.

In Proverbs 8:1-3, Wisdom is described as a woman with the pronouns “she” and “her” used repeatedly. Then later in verses 22-31, Lady Wisdom is described with the exact language Jesus is described with in 1 Corinthians 1:24 and Revelation 3:14. Even The Gospel Coalition says, “To put it simply, if Jesus is God’s Wisdom, then Proverbs 8 must be a reference to Jesus.”

If Christians interpret the second person of the Trinity as Lady Wisdom incarnating as Jesus the Son, then Jesus was either transgender or intersex.

Intersexion: An interview with Cynthia Vacca Davis

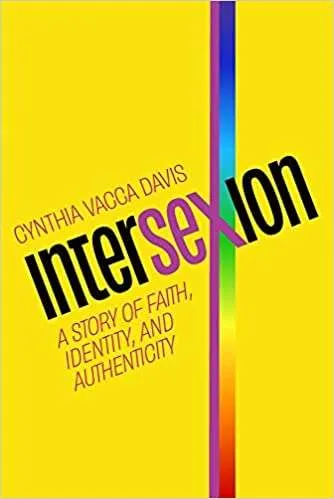

Given the fact that so few Christians understand intersex people, let alone have considered intersex people as good and whole revelations of the incarnated intersex body of God, I decided to interview author Cynthia Vacca Davis about her book Intersexion: A Story of Faith, Identity, and Authenticity.

Cynthia Vacca Davis

Intersexion is a dual memoir in which Davis — an LGBTQ ally — and Danny — an intersex person who came out of conservative evangelicalism, come together as friends in pursuit of wholeness. Her book was listed by Q Spirit as one of the top LGBTQ Christian books of 2022.

What are the messages conveyed to intersex people regarding their human identity in light of their bodies? Are they positive, negative or perhaps mixed messages? How are these messages conveyed to them either verbally or nonverbally? And who are these messages coming from?

In talking with people about intersex over the eight years I have been involved in writing and advocacy, I have seen reactions ranging from empathy and interest to skepticism and disgust — and these reactions are coming to me as an ally as opposed to an intersex person living every second of their life in their body.

“I was feeling just a fraction of what Danny had lived with his entire life and it had reduced me to near desperation in a year.”

My introduction into intersex advocacy was a baptism by fire: In a year, I had lost a tenure-track professorship, was ousted from my church and had to take on a bunch of exhausting jobs to come up with the money to finish my MFA. I was feeling just a fraction of what Danny had lived with his entire life and it had reduced me to near desperation in a year.

That I could hit such a low in that amount of time spoke volumes. I cannot imagine how the barrage of messages and opinions can accumulate over a lifetime, but having so many unsolicited opinions around your identity and personhood has to be exhausting.

Some common reactions I hear are questions around frequency — people seem to need to know numbers, and to want those numbers to be small. If intersex is rare, people don’t have to expend too much brainpower on the issue and feel justified dismissing it as an outlying issue.

To me the question “How many people does this really impact?” equates to “Do I really need to think this through or is it rare enough not to be relevant?”

Most of this line of questioning has been from conservative Christians who are anti-gay. It almost seems like they’re annoyed that the clear, biological nature of intersex throws a question mark into their theology, and they want to be able to put intersex into a narrowly defined category of “rare exception that I don’t need to think about much.”

Most of this line of questioning has been from conservative Christians who are anti-gay. It almost seems like they’re annoyed that the clear, biological nature of intersex throws a question mark into their theology, and they want to be able to put intersex into a narrowly defined category of “rare exception that I don’t need to think about much.”

I’ve also had people question the validity of Danny’s story, saying, “That’s not possible,” or accuse me of sensationalizing the details.

I remember conversations with Danny where we’d talk about different reactions we’d heard and I remember him saying, “But yet, I exist! I am not a unicorn!”

At times, the message definitely seemed to be that Danny’s existence was something that had to be proved scientifically and then vetted spiritually, which was definitely weird.

What are some games intersex people feel they have to play in order to be accepted in society as a result of those messages? And how might those games keep them from being their authentic whole selves?

I’ve heard it said many times in the intersex community that if you have met one intersex person, then you have met one intersex person. It’s important not to generalize the intersex experience as looking one certain way or requiring a specific set of coping mechanisms.

“He instinctively knew his body — his very existence — was an affront to the beliefs around gender and sexuality he heard at home and church.”

There are many different types of intersex and many ways to live as an intersex person. In Danny’s case, though, he lived as a woman until he was in his early 40s because he instinctively knew his body — his very existence — was an affront to the beliefs around gender and sexuality he heard at home and church. He didn’t see himself represented at all, and that was terrifying enough for him to live in misery as a female for decades as opposed to stepping into his authentic male identity, which he was only able to do when his life was on the line.

Some Christians frame the incarnation of Jesus as God’s reaction to sin, while others conceive it as God becoming what God loves. How could imagining the incarnation of God as a body-affirming overflow of love encourage the embodied presence of intersex people in themselves and among others in ways that framing the incarnation of God as a reaction to sin and brokenness would not?

That’s such a great question because it gets to the heart of whether to view an intersex person as defective or “fearfully and wonderfully made.” And going all the way back to why Jesus chose to walk among us can really frame our view of not just intersex people, but all of humanity.

“If we see the incarnation of Jesus through a sin lens, we see only brokenness.”

In an open, affirming view, we can see an intersex body as encompassing more humanity; or offering a beautiful image of duality in the world. If we see the incarnation of Jesus through a sin lens, we see only brokenness — a brokenness that makes it easy to write off intersex — or really anything “different” as a consequence of living in a fallen world.

I sat at a board room table at a Christian university being grilled about intersex. My future at the university was dependent on my answers. Of all the things I was asked, the most baffling question was, “Where do you see the sin in your friend Danny’s situation?”

That question stopped me in my tracks, because I never for a moment considered there to be sin in being intersex. But I came to realize the only way they were able to process the existence of intersex people was through the lens of a sinful world. In their minds, intersex would not exist without sin.

Do you know of any positive examples of churches embracing intersex people?

I think there is a clear divide between mainline evangelical churches who I do not see affirming examples from and affirming churches that I would not personally categorize as evangelical.

Are there any conservative evangelical churches that embrace intersex people that you know of?

Tolerate, perhaps, but embrace — I haven’t seen it.

Are they more willing to embrace intersex people than they are to embrace transgender people?

I definitely have had conversations with Christians who are eager to adopt a clinical, medical view of intersex so they can definitively differentiate it from transgender. They can accept intersex as a “medical issue.” But there are so many problems with this approach, the first being that a “medical issue” implies that intersex itself is problematic.

It’s also murky from a scientific standpoint. Intersex and transgender are absolutely different but also have points of connection that even experts don’t agree on. Some people have dualities on the chromosomal level that don’t manifest physically, so it is possible to be intersex and not know it. From that perspective, it’s possible that some people who just don’t feel right in their bodies — people conservative Christians might think of as ‘just wanting a sex change’ — could still have a biological basis for the disagreement they feel with their assigned gender.

There are so many stories of people who find out in adulthood that they aren’t the gender they think. Most people go their whole lives without having chromosomal testing.

Also, some intersex people, like Danny, are also trans because they opt to change how they present. Danny was miserable in his assigned gender. It never fit. When he had the support and language he needed to explain his intersex identity, he then was able to change his outward presentation to match who he’d always been inside — so Danny is both intersex and trans.

For all these reasons, I am uncomfortable with the need some people have to distance intersex from transgender — yes, they are different, but keeping intersex as a rigid category apart from transgender can be a barrier to being affirming when those two things intersect.

Do you know of any conservative evangelical complementarian churches that allow intersex people to get married or to hold church leadership? Or do they require celibacy and non-leadership roles for all intersex people?

I cannot speak broadly on what individual churches do, but I will say that in the conversation with the Christian university I worked for — the answer they were looking for when they asked me about the sin in Danny’s situation was around the need for celibacy. The administrative leaders expressed to me that being intersex was like alcoholism — you may be born a certain way, but then it is your responsibility to stay away from certain things like alcohol or sexual relationships as a moral obligation.

“You may be born a certain way, but then it is your responsibility to stay away from certain things like alcohol or sexual relationships as a moral obligation.”

Essentially churches that hold that view are asking intersex people to live a less-than-full life devoid of intimacy, yet there seems to be a culture of grace around church leaders who are not faithful to the spouses they are encouraged to have.

How should allies of intersex people appeal to non-affirming Christians to influence them toward affirming and embracing intersex people?

As a writer with a journalistic background, I claim stories as my life’s work. I am a believer in the power of stories. If we allow stories to be our teachers, we will learn more than we ever could imagine.

Is appealing to scientific data helpful?

It can be, but it also invites debate. Just yesterday on Twitter I saw something that perfectly illustrates this. Someone tweeted how mind expanding it had been to learn that being intersex is as common as red hair. The tweet blew up with both affirming comments but also a sea of nay-sayers determined to undermine the statistic, pick through methodologies and discredit sources. The conversation became unproductive pretty quickly.

But you cannot debate a story. A well-supported, fully told story can sometimes do more heavy lifting than a scientific study. Jesus knew this, too. He came to tell stories. Studies can add to a knowledge base, but stories create empathy, and there is nothing more powerful than empathy. We see this sometimes in evangelicals who have a change of heart after a family member comes out as gay. They didn’t have empathy for nameless, faceless people but a family member’s experience (story) changed their view.

“A well-supported, fully told story can sometimes do more heavy lifting than a scientific study.”

Is having to appeal to scientific data or Bible verses in order to affirm their humanity dehumanizing to intersex people?

Although there can be a validating component to data (hey! I am not alone, there’s language for what is happening to me) I also find it frustrating to have to “prove” the legitimacy of who you are as a human.

Is it possible to appeal to intuition and our common humanity, or are those simply non-factors for non-affirming Christians?

I see my book as a test balloon for this idea. So many of my readers to date have been progressive Christians, but there’s a sense there of preaching to the choir. I want to get Danny’s story into the hands and hearts of people who are skeptical, people who are willing to look at something they don’t understand and dive into another person’s experience. I am so hopeful that eventually I can find inroads to those audiences. I am so hopeful they exist.

How can we be present with intersex people in relationships that affirm their goodness and wholeness?

Be the kind of person who an intersex person feels safe confiding in. My friendship with Danny began simply because I had a reputation as a “safe” person. When Danny got to the end of his ability to live in secret, he had to take some risks. I was one of those risks.

Statistically, almost everyone knows someone who is intersex, but most will never know that because it’s too dangerous for an intersex person to be vulnerable and transparent unless they have a reasonable expectation that you are someone they can trust. If you have a history of having strong, negative, anti-LGBTQ opinions, you likely do know intersex people — they just aren’t telling you about it.

Rick Pidcock

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He recently completed a Master of Arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.

Related articles:

What is a woman? | Opinion by Anna Sieges

My story of being trans and the conservative Baptist school that made me that way | Opinion by Triss Ingels

When forced to choose between their ministry and their transgender child, this family chose love

Why being transgender is not a sin | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Seven things I’m learning about transgender persons | Opinion by Mark Wingfield