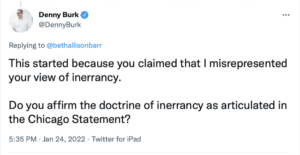

“Do you affirm the doctrine of inerrancy as articulated in the Chicago Statement?” demands Denny Burk, professor at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, tweeting his line in the sand to defend what he thinks are attacks against historic orthodoxy by the ever-so-dangerous Beth Allison Barr.

Bringing up the Chicago Statement on Inerrancy is a common tactic the TheoBros use to simplify their control of a conversation down to the false dichotomy of being in or out based on your affirmation of an unrelated document. It has become a litmus test for orthodox belief and a handy means of discrediting anyone with an opposing theological view.

Thankfully, historians such as Barr of Baylor University and Kristin Du Mez of Calvin College are not falling for these tricks.

Thankfully, historians such as Barr of Baylor University and Kristin Du Mez of Calvin College are not falling for these tricks.

Much could be said about the weaponization of the Chicago Statement on Inerrancy. But where did the Chicago Statement come from? What is it? Does it accurately communicate what the Bible is? Can it be signed in a non-weaponizing way? Or is it a fundamentally flawed document that fails to reflect the Bible accurately and that is inherently weaponized by white male supremacy?

The Chicago Trilogy

Many people do not realize that the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy actually is the first of three statements organized by the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy from 1978 to 1986. Following their statement about inerrancy in 1978, the council reconvened in 1982 in order to release a statement on Biblical Hermeneutics and again in 1986 on Biblical Application.

The 1982 statement on biblical hermeneutics says: “While we recognize that belief in the inerrancy of Scripture is basic to maintaining its authority, the values of that commitment are only as real as one’s understanding of the meaning of Scripture.”

Its authors defined biblical hermeneutics as “the study of right principles for understanding the biblical text,” contrasting the theoretical understanding of Scripture as ancient literature from the experiential understanding of Scripture as “personal knowledge of the God to whom it points,” and arguing that biblical hermeneutics combines the best of both worlds.

The 1986 statement on biblical application explores such topics as abortion, marriage with the “husband as head” and the wife “as helper in submissive companionship,” “sexual deviations,” politics, war, economics, work, wealth and poverty, and environmentalism within a conservative evangelical complementarian worldview and states that with this “trilogy of Summits … the doctrine of inerrancy has thus been defined, interpreted and applied.”

The ‘humble’ authority of the inerrantists

The trilogy begins by emphasizing the “infallible authority” of Scripture, while claiming to be offered “in a spirit, not of contention, but of humility and love.” It admits: “We claim no personal infallibility for the witness we bear.”

“Anyone who allows Scripture to deliver its own message on these matters will end up approximately where we stand ourselves.”

But then the authors go on to say, “Because this loss of confidence (in the “total trustworthiness of the Scriptures”) leads both to loss of clarity in stating the absolutes of authentic Christianity and to loss of muscle in maintaining them, the task was felt to be urgent. … The Council sees what has been accomplished as cause for profound thanksgiving to God, from every point of view.”

They conclude that “anyone who allows Scripture to deliver its own message on these matters will end up approximately where we stand ourselves.”

When taken as a whole, the inerrancy trilogy is designed to maintain infallible authority with humility, clarity and muscle — with the assumption that all orthodox Christians will mostly agree with its writers. But where does the authority actually lie? While claiming the authority rests in the Bible and while giving lip service to humility, the authority ultimately is held by the writers of the inerrancy trilogy, who demand that all Christians submit to their view of the Bible.

The inerrancy of white male supremacy and the invisibility of the rest

The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy originally was signed by 334 people. After looking up every name on the list and asking some of my seminary professors to review the list, I was able to confirm four Hispanic men, one Black man, one Asian man, and five white women who signed the document. But those 11 people are merely drops in a sea of white males.

Because the statement was signed in 1978, the vast majority of those white men were theologically trained decades earlier in segregated seminaries by other white men who had created theologically fueled systems of white supremacy.

Where are the Hispanic, Black, Asian or Middle Eastern women? Where are LGBTQ Christians? Why are there not more Hispanic, Black, Middle Eastern and Asian men?

“In the world of the Chicago inerrancy trilogy, anyone other than straight white men is virtually invisible, nowhere to be seen.”

In the world of the Chicago inerrancy trilogy, anyone other than straight white men is virtually invisible, nowhere to be seen, with apparently nothing to offer to the white men who set the rules.

In what age?

The Preface to the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy begins by stating: “The authority of Scripture is a key issue for the Christian Church in this and every age.”

We don’t even get one sentence into the statement before its writers communicate a lack of awareness of the privilege they have in even holding a Bible. For most of humanity throughout time, access to the Bible was impossible.

When the council of church teachers met at Jerusalem in Acts 15 to discuss whether new believers were bound to become circumcised “according to the custom taught by Moses” — the only Scripture they had — the council instead decided that “it seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us not to burden you. … Farewell.”

As the church continued beyond the time of the apostles, the question of authority continued to be up for discussion. In The Story of Christian Theology, church historian Roger Olson says, “The Christian Bible, or Canon of Scripture, evolved slowly and painfully with much controversy. … Of course the apostles left behind writings. … These apostolic writings were not bound together between leather covers with ‘Holy Bible’ stamped on the front, however, and in (A.D.) 100 the idea of a ‘New Testament’ as a canon of Christian Scriptures was yet undeveloped. That is not to say that no Christians thought of the apostles’ writings as Scripture. Most Christians around that time probably did consider authentic writings of apostles very special in some sense, and occasionally second-century Christian church fathers did quote them as Scripture. The problem was that no single church or even region of Christianity — such as Rome or Ephesus or Egypt — had a complete collection of the apostolic writings, and there was widespread disagreement about which books and letters were genuinely written by apostles.”

The leather-bound single book with “Holy Bible” stamped on the front and printed in the language of common people didn’t exist until the 15th century. And according to Wycliffe Global Alliance, even today “1.51 billion people, speaking 6,661 languages, do not have a full Bible in their first language.”

“The leather-bound single book with ‘Holy Bible’ stamped on the front and printed in the language of common people didn’t exist until the 15th century.”

So how is the authority of an inerrant Scripture key for “this and every age,” when it hasn’t even been accessible by billions of people today or the majority of humankind throughout history? If the God described in the Bible really cares about the suffering of the poor and the oppressed, and if an inerrant Bible is so fundamental to saving them from eternal suffering, then why has the Bible mainly been accessible to the privileged and the powerful throughout history?

Clutching and clinging to authority and certainty

In Tradition and Apocalypse: An Essay on the Future of Christian Belief, David Bentley Hart says: “This is not faith. It lacks even the dignity of honest superstition. It is fideism, the most decadent of religious states. And it is always in a state of desperation. The Protestant fundamentalist clinging to literalist scriptural inerrancy, the Catholic traditionalist clinging to a brutally reductive concept of infallible dogmatic pronouncements, the Orthodox traditionalist clinging to the nonexistent unanimity of the fathers — all are merely clutching at whatever bits of flotsam seem to them most buoyant atop the ocean of historical contingency, following the shipwreck of Christendom. Real faith, by contrast, is something at once far less frantic but also far less certain of itself.”

When one examines the 13 articles of affirmations and denials in the Chicago Statement, the clutching and clinging to authority and certainty in the face of reality become quite apparent.

Article I denies that the Bible receives its authority from the church, but fails to recognize what Olson referred to as the “widespread disagreement” within the church about which books should be included.

Article II denies that creeds, councils or declarations have authority like the Bible does, but seems unaware of how those creeds, councils, declarations or modern conservative evangelical statements affect their interpretation of the Bible.

Article VIII affirms that God used the personalities and literary styles of the biblical authors. Then Article XII affirms that the Scripture is inerrant in areas of history and science, which implies that the authors are either unaware of or being dishonest about how the literary styles of the biblical authors included ways of telling history or viewing cosmology that were fundamentally different than the ways we talk about history and science today.

Article X affirms that inspiration applies only to the original text of Scripture, while denying that the fact these texts no longer exist is problematic. What the authors consider to be “inerrant,” according to their own words, are documents they’ve never seen.

“Article X affirms that inspiration applies only to the original text of Scripture, while denying that the fact these texts no longer exist is problematic.”

Additionally, the authors’ view of there being an original autograph of each book fails to consider how the Bible was pieced together and designed over time.

As Olson observed, “You can’t make authority depend on inerrancy and then say no existing Bible is inerrant without calling every Bible’s authority into question. It’s a hole in inerrantists’ logic so huge even a sophomore can drive a truck through it.”

Olson also notes: “To the untrained and untutored ear, ‘inerrant’ always and necessarily implies flawless perfection … . But even the strictest scholarly adherents of inerrancy kill that definition with the death of a thousand qualifications … . How many people in the pews know about these qualifications held by many, if not all, scholarly conservative evangelicals? … When I teach these qualifications to my students … I have them read the Chicago Statement on Inerrancy and most of them laugh at the twists and turns it makes in order to qualify inerrancy to make it fit with the undeniable phenomena of Scripture.”

Much more could be said about the articles in the Chicago Statement, including detailed analysis of the Bible itself. But at its core, the Chicago Statement proposes a view of inerrancy that denies how the Bible was formed, that denies church history, that denies how the social location of the authors affected their views of history and science, that denies modern science, that denies the authors’ own culturally formed biases, and that depends on original manuscripts that no longer exist.

In the words of David Bentley Hart, that is the very definition of a fideism in a state of desperation, clutching and frantic clinging.

Opening up the conversation by listening to others

One of the reasons I listen to liberationist theologians is that, unlike the promoters of the Chicago Statement, they are aware of and honest about their perspectives.

In Lift Every Voice: Constructing Christian Theologies from the Underside, Susan Thistlethwaite and Mary Potter Engel say that “liberation theologians hold that no value-neutral posture is possible.” This means that every person who reads the Bible reads from a perspective that contains values and biases that are often unnoticed.

In The Liberation of Theology, Juan Luis Segundo says that “the prevailing interpretation of the Bible has not taken important pieces of data into account.”

“The Chicago Statement was written overwhelmingly by conservative evangelical white Western men at the height of the most powerful social location in world history.”

Whatever one thinks about the Bible, the fact is that the Bible was written by people who were processing their fear and experience of exile at the hand of empires. But the Chicago Statement was written overwhelmingly by conservative evangelical white Western men at the height of the most powerful social location in world history, who assume that anyone that takes the Bible seriously will “end up approximately where we stand ourselves,” while refusing to listen to those on the underside of their power that their communities have oppressed.

Due to these biases, Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza says in The Challenge of Liberation Theology: “The interpreter must make her/his stance explicit and take an advocacy position in favor of the oppressed.”

For those of us who are still interested in engaging with the Bible, there are entire worlds of interpretational beauty and liberating power that become available when the Bible can be opened up by the perspectives of the oppressed rather than summed up by the proclamations of the powerful.

For the writers of the Chicago Statement, however, “To stray from Scripture in faith or conduct is disloyalty to our Master.” And unfortunately, the framework, language and makers who formed the Chicago Statement have created an interpretational system where that master is the voice of conservative evangelical white patriarchal men.

Four of the six Southern Baptist Convention seminaries now require faculty to affirm the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, in addition to the Baptist Faith and Message 2000, separate statements of faith unique to that school, and often additional doctrinal statements.

Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Texas requires affirmation of the Danvers Statement on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood and the Nashville Statement on gender.

Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in North Carolina requires affirmation of the Danvers Statement.

Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kentucky, in addition to its own historic “Abstract of Principles,” has adopted the Danvers Statement on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood and the Nashville Statement on gender.

Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Missouri requires affirmation of the Danvers Statement on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood and the Nashville Statement on gender.

Only New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary and Gateway Seminary in California do not mention the Chicago Statement on a published list of doctrinal requirements on their websites.

Rick Pidcock

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a bachelor of arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He recently completed a master of arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.

Related articles:

This is a tale of testicles, fertility, the length of men’s hair, and one bizarre tweet | Analysis by Rick Pidcock

Debate over women in Southern Baptist pulpits flares on social media

Meet the TheoBros, who want you to know they’re right about everything | Analysis by Rick Pidcock