The Maryland General Assembly passed the first of a series of race laws in 1664. The first iteration transformed enslavement to a lifelong identity rather than a state of indenture or a condition that could be changed.

Lisa Sharon Harper (Photo © Joy Guion Bailey)

The Maryland General Assembly kept English common law, which passed citizenship through the lineage of the father. Unlike with the Virginia House of Burgesses, Maryland legislators perceived their problem to be the mixed-race progeny of white women gaining their freedom. To boot, the assembly declared that the children of marriages between white women and enslaved Black men would be enslaved for life, and all their descendants after them. The White woman also would become the enslaved property of her husband’s master until her husband’s death. Finally, the children of married white women and enslaved Black men would be enslaved for life if born after the law went into force. But if born before the law passed, they would serve their father’s master for 31 years.

Fortune’s story

Fortune’s father was enslaved, but she stood in that Somerset County courtroom to face the prospect of indenture precisely because she was not enslaved upon birth. She likely had been able to live free until she was 18 years old. Why? Because of white privilege.

Lord Baltimore Charles Calvert

Lord Baltimore Charles Calvert, grandson of the first Lord Baltimore, brought 16-year-old Eleanor Butler with him from England to Maryland in 1681— six years before Fortune was born. Butler fell in love with and married an enslaved man, identified in court records as “Negro Charles.” She appealed to her friend Lord Baltimore to repeal the 1664 law, which required Eleanor’s immediate enslavement and the enslavement of all her children for life, in perpetuity.

Calvert immediately moved to repeal the original 1664 race law. It was rescinded and replaced with the 1681 race law, which acknowledged an unscrupulous practice that had developed since passage of the original law. Masters were forcing their white indentured servant women to marry the masters’ enslaved African men. This practice reaped exponential increases in planters’ free labor force over generations.

A change in 1681

Maryland’s legislature limited the scope of the law to forced marriages between Black men and white women and dropped the requirement that their children be enslaved. The result? As of 1681, all newborn mixed-race children would be born free.

According to Maryland State Park historian Ross M. Kimmel, Butler benefited only marginally from Lord Baltimore’s efforts. She was still enslaved because her marriage took place before the 1681 law was passed. But as a white woman, she was afforded liberties not usually afforded to enslaved people.

Still, her children and descendants were born after the 1681 repeal. They should have been born free. The 1681 law provided the children free status regardless of which parent was white. Butler’s grandchildren were enslaved. They appealed to the courts in 1710. Around the time of the Revolutionary War, they finally won.

Fortune’s fate should have been equally clear. She stood before the judge in 1705. The 18-year-old girl listed as a “mulatto” in court documents should have been subject to Lord Baltimore’s 1681 law. But in the interim, the Maryland General Assembly soured on Lord Baltimore and replaced his law with a harsher, more comprehensive, racialized legal structure in 1692 — five years after Fortune’s birth.

Trapped by a new law

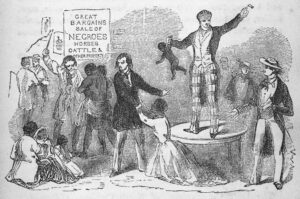

The new law protected white women and their children from slavery by removing the financial impetus for their enslavement. They would be indentured to the local parish, not enslaved by the master. The parishes were ordered to transact the sales of enslaved Black men and indentured white and mixed-race servants to white families. The proceeds of those sales assisted poor whites in the parish.

“The church was the principal protector and manager of white supremacy through the trade of enslaved and indentured human beings in America’s second colony.”

In essence, at the turn of the 18th century, the church itself became the primary auction block in Maryland. The grotesque nature of this arrangement cannot be overstated. The church joined the banks, insurance companies, shipping companies, iron works and other institutions in crushing the image of God on this land. The church was the principal protector and manager of white supremacy through the trade of enslaved and indentured human beings in America’s second colony.

Image: New York Public Library, 1853

According to the 1692 law, a child of a white mother could not be enslaved. Period. The race of the mother became the determining factor of slave or free status. But intolerance of interracial relationships hardened in this law. White women and their children still could be indentured as penalty for miscegenation — married or not. A penalty of seven years indenture was given to the woman and 21 years indenture to the child if the parents were married — or 31 years indenture for the child if the parents were not married.

Standing before the judge

Standing before the court, 18-year-old Fortune was born free and should have remained free according to Lord Baltimore’s 1681 legal turnabout. But, of course, the application of law is different from the law itself. Fortune’s fate was largely dependent on the judge, especially in this formative period of Colonial race law. Would the judge see and honor the legislative merits of Fortune’s fight to stay free? Or would his sensibilities align more with the racialized hardening of the times?

I imagine Fortune, awaiting the judge’s decision, looking out a window to her left, just behind the prosecutor offering his closing argument for Fortune’s indenture. Her heartbeat races. Beads of sweat form on her forehead as she wipes sweaty palms on her dress. She clasps her high yellow hands — the only thing she has to hold on to in this moment is herself. I imagine Fortune thinking of the woman who birthed her, Maudlin.

“He, too, lived on the other side of whiteness, daily surviving the branding iron of legal Blackness.”

We know so little of Maudlin other than the fact that she was an indentured Ulster Scots woman married to an Ulster Scot, George Magee, with whom she bore three children. Maudlin’s first child was John Magee, born one year before Fortune. The year after Fortune’s birth, Maudlin and George brought Peter Magee into the world, and three years after that she gave birth to Samual. Historian Paul Heinegg cites the judicial record of this court proceeding, as well as land tax records indicating that Maudlin was alive and living with her husband, George, as late as 1705 — the year of this trial. Yet, there is no record of her presence.

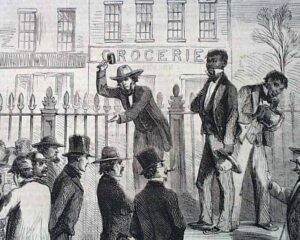

Print from New York Illustrated News, Jan. 26, 1861, captioned: “Annual Sale and Hiring of Slaves at Montgomery, Ala.”

With possible moments left in her free life, I imagine Fortune’s thoughts turning to her father, Sambo. He, too, was born free. He, too, was bound and sold as a teen. He, too, lived on the other side of whiteness, daily surviving the branding iron of legal Blackness.

Enslaved to Constable Peter Douty, Sambo and his wife were willed free and given land upon Douty’s death, five years after Fortune’s trial. We know that he and Fortune were close. She would take his surname and later live with him on that land. Evidence suggests Sambo may have been a healer. His son, Harry, was a practicing doctor in 1750. He credited his knowledge to an “old experienced Guinea doctor” — likely Sambo, who was from a region that intersected Senegal, Guinea and Mali, before national boundaries were drawn. Sambo was a learned man who passed down what he knew to the next generation. It makes me wonder what he passed down to Fortune that was in turn passed down to us.

Fortune stood at the precipice of bondage with only the memories of her freedom and her family to give her comfort. Indenture was just as brutal as slavery. Indentured servants were whipped and maimed as punishment. Fortune did not know what was in store for her, and she had no control over it — perhaps that combination is the essence of the terror of bondage, whether enslaved or indentured. She held within her both this unknowing and a complete lack of control over her own body, life and family.

When I imagine 18-year-old Fortune in that courtroom, I find my own breath shortening in anticipation of the ruling. With short breaths, Fortune likely listened as the judge asked her if she understood her sentence. She was hereby ordered to retroactive indentured service to Mrs. Mary Day until the age of 31.

Twenties gone.

Freedom gone.

Safety for herself and her daughters? Gone, gone.

Lisa Sharon Harper is a speaker, writer and activist and founder of the consulting group Freedom Road. She is the author of several books, including her latest, Fortune, from which this column is excerpted. She is a columnist for Sojourners and a senior fellow at Auburn Theological Seminary. Harper earned a master’s degree in human rights from Columbia University and previously served as chief church engagement officer for Sojourners. Content taken from Fortune by Lisa Sharon Harper, ©2022. Used by permission of Baker Publishing.

Related articles:

What to do if you unearth a history of slavery in your church, college or institution?

How slavery still shapes the world of white evangelical Christians | Opinion by Richard T. Hughes

What Toni Morrison taught me about my people, the Quakers | Opinion by Becky Ankeny