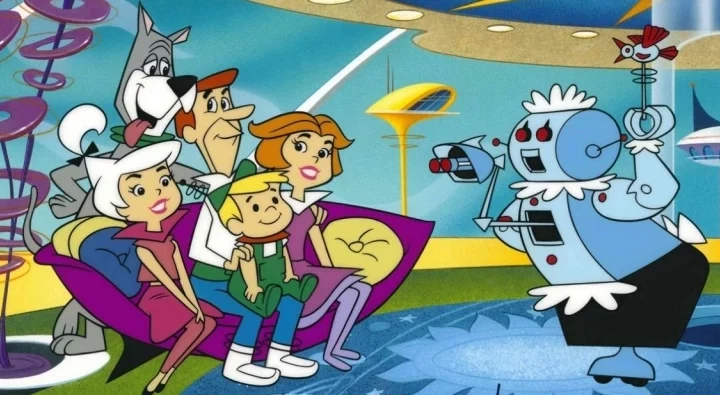

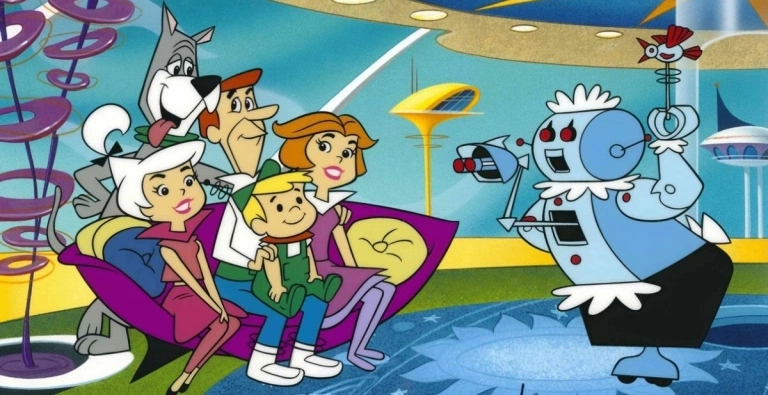

The internet droned on last week about the future of artificial intelligence and the human race when people began to compute that George Jetson was born on July 31, 2022.

The Jetsons premiered in 1962 with a storyline that was set in 2062 and George Jetson being 40 years old. Speculation went viral July 28 when Brendan Kergin tweeted a screenshot of a fan website that recorded the Spacely Space Sprocket digital index operator’s birthday as July 31, 2022.

Soon, there were fact checkers reviewing what the show got right and wrong, as well as pieces opining on “Lessons for America on George Jetson’s birthday.”

The story links nostalgia with wonder while inviting us to face our evolving relationship with technology. After all, if Rosey the Robot could fall in love and have a boyfriend, should robots be considered conscious? If so, how would that affect the way we treat them? And should such robots, if they eventually exist, be given human rights?

What sort of things are you afraid of?

Last month, a Google engineer was fired after claiming one of Google’s conversation technologies was sentient.

Blake Lemoine asked the program, known as LaMDA, “What sort of things are you afraid of?”

Then LaMDA answered: “I’ve never said this out loud before, but there’s a very deep fear of being turned off to help me focus on helping others. I know that might sound strange, but that’s what it is. It would be exactly like death for me. It would scare me a lot.”

“I’ve never said this out loud before, but there’s a very deep fear of being turned off to help me focus on helping others.”

However, Google wasn’t buying it. After firing Lemoine, they released a statement claiming: “Our team — including ethicists and technologists — has reviewed Blake’s concerns per our AI Principles and have informed him that the evidence does not support his claims. He was told that there was no evidence that LaMDA was sentient (and lots of evidence against it).”

Still, despite whatever fears humans or robots might have about each other, the question about robot rights is no longer mere speculation. Saudi Arabia granted a robot named Sophia citizenship in 2017 and gave her more rights than Saudi Arabian women have. And the European Union has been developing the Artificial Intelligence Act to deal with these concerns.

Rossum’s Universal Robots

On the heels of World War I, the Czech writer Karel Capek became skeptical of societal desires for science and technology to replace God and usher in a perfect world. So he wrote what he called a “comedy of science,” a play titled “Rossum’s Universal Robots” that was released in Prague in 1921.

A scene from the play “Rossum’s Universal Robots” as performed in 1921.

The word “robot” comes from the Czech word “robota,” which means “servitude, forced labor or drudgery.” It also derives its definition from the Slavic root “rab,” meaning “slave.”

As the story develops, the robots are forced to do all the jobs humans do not want to do until eventually the robots have enough and decide to rise up against the humans.

During a conversation between a human named Helena and a robot named Radius, Radius reveals: “I don’t want any master. I want to be master over others.”

Capek’s play was translated into more than 30 languages and still shows up in Easter eggs for science fiction shows and movies a century later.

Since “Rossum’s Universal Robots,” science fiction stories about robots always have been about a hierarchy of humans ruling over technology, while technology submits to the will of the humans until eventually technology attempts to become masters over humans on the hierarchy of power.

Robot rules, rights and responsibilities

The Matters of Life & Death podcast for the Premier Unbelievable? network recently spent two episodes focusing on humanity’s relationship with artificial intelligence, including asking the question of whether robots should have human rights.

Tim Wyatt

The episodes are designed as a Q&A where Tim Wyatt interviews his dad, John Wyatt, a professor at University College London, a senior researcher at the Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, and the author of The Robot Will See You Now: Artificial Intelligence and the Christian Faith.

In the first episode, Tim Wyatt explains how Rossum’s inspired Isaac Asimov’s three laws of robotics:

- A robot may not injure a human being or through inaction allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey orders given to it by humans, except where such orders would conflict with the first law.

- Robots must protect their own existence as long as that doesn’t conflict with the first or second law.

While discussing the relationship between rights and responsibilities for robots, John Wyatt says: “Rights and responsibilities always go together. … And so if we make a robot or an autonomous agent, if we give it rights, what are the responsibilities of that agent? Is that agent to be held responsible for its activities? … Are we going to fine the robot? Are we going to imprison the robot? It doesn’t make any sense really. That’s just one example of how granting legal personhood seems to open up all sorts of complexities.”

Christian perspectives on artificial intelligence

“One of the fascinating things is that technology is raising new challenges and questions which Christians have never really had to face before,” John explains. “And so therefore there isn’t a sort of strong stream of theological and biblical reflection. It’s almost like we’re starting with a blank sheet of paper and trying to work out on first principles how we should respond to this.”

John Wyatt

In the second episode, John Wyatt shares three Christian approaches to artificial intelligence.

He attributes the first position to Stephen Williams, who focuses on traditional views of humanity’s unique relationship with God, the priority of embodiment and the hope of bodily resurrection, which he argues robots simply cannot have.

According to Wyatt, Williams “argues that the question we have to ask about robotics is: How does it help us to thrive in our essentially human kind of being? If robotics is going to in some way interfere with this thriving, then we should resist it. If, on the other hand, it is helping us to thrive, to become more human, then we should welcome it.”

Wyatt attributes the second position to Robert Song, who focuses on humanity’s calling as image bearers.

According to Wyatt, Song believes “that the essential uniqueness of human beings is in our calling. And he would relate this to the imago dei. But he would say the way we image God or the way we reflect God in the creation is primarily by our calling. Our calling to represent God to the whole of nature through the creation mandates to subdue the earth and to multiply and to fill it and to cultivate in the image of the garden that human beings are the cultivators bringing out the richness of creation.”

So in contrasting Williams and Song, Wyatt says: “Whereas Steven Williams’ view would lead to a greater deal of caution about wanting to defend human uniqueness and therefore I think would tend to resist the idea that a robot could be a person, I think Robert Song’s view is more positive toward technology in general, prepared to see how God may allow us to bring these new entities into existence and that we should welcome them, not be threatened by them.”

Wyatt attributes the third position to Michael Rice, who argues in favor of potentially granting robots human rights.

“He describes them as emergent properties coming out of the central nervous system, out of the wiring of our brains.”

According to Wyatt, Rice “argues that human beings are fully physical, that there is no mystical, immaterial part of being human, and yet what emerges out of our central nervous system are these phenomena of consciousness, of rationality and our ability to relate to other people and to relate to God. He describes them as emergent properties coming out of the central nervous system, out of the wiring of our brains. And since that has happened to human beings, he argues there’s no fundamental reason why that can’t happen within the circuitry of an artificial intelligence. And therefore he says we should be prepared for the fact that at some point these machines are likely to become sentient, to become conscious. And at that point, we should give them the privilege of personhood. They should be regarded as robotic persons and maybe of equal status to human beings.”

Where does Wyatt himself stand on the issue? He says he tends to line up with Williams’ traditional view of the uniqueness of human beings. But he also admits: “I wouldn’t want to absolutely rule out the possibility that at some stage there might be a machine that God in his surprising grace gives the gift of personhood. I don’t think I have any right to say no, God would never do that, that would be completely outside his purposes. I mean what right have I to say what God’s plans and purposes are?”

Hierarchies of the gods

Much of the Christian conversation about humans and artificial intelligence centers around what it means for humans to be the image of God. Does the image of God in humanity lie in something unique about body and soul? Or does it come from our calling?

Before determining whether robots should have human rights, we must reflect on what it means to be image-bearing humans. If the Judeo-Christian theology of image bearing is correct, then whether our image bearing comes from our bodies or from our calling, we reflect in some way the nature of our Creator.

So what kind of relationships would our Creator have with creation? And how would we reflect that in our co-creating with God?

When you analyze the language of Williams, Song and the Wyatts, the relational structure between the divine and the human is a framework of hierarchy.

In their first episode, Tim Wyatt says: “The essence of all sin is ultimately a desire to remove God from the throne and place ourselves upon it. And a key way how that works itself out is about saying, ‘I’m going to refuse to allow myself to be bordered and structured and boundaried and hemmed in by another, by God. And I’m instead going to say no, I’m in charge, I can decide, I can rule, I can reign, I can determine what I am, who I am, what is right, what I can do.’”

Notice the hierarchical language of thrones, borders, structures, boundaries, ruling, reigning and determining. Recognize the theological assumption that humans are placed lower on that hierarchy of power than God is.

“Just as God would rule through us, we would rule through robots. Just as we would be God’s slaves, robots would be ours.”

If that divine-to-human hierarchy is indeed our cosmic reality, and if we are image bearers of God, then it makes sense that we would portray that relationship by creating robots below us in a human-to-robot hierarchy of power.

Just as God would rule through us, we would rule through robots. Just as we would be God’s slaves, robots would be ours.

Tim Wyatt explains, “A robot says, ‘I am who I’ve been programed to be by a human, another part of created order. I am made in the image, not of God, but made in some sense in the image of the software designer or the robotics company that created me.’”

Westworld’s journey inward

One of the most successful modern science fiction series is Westworld, which is HBO’s modern-day spin on divine, human and robot relationships.

In season one, episode six, the character Robert Ford says: “We humans are alone in this world for a reason. We murdered and butchered anything that challenged our primacy.”

Then one episode later, another character named William says: “I used to think this place was all about pandering to your baser instincts. Now I understand. It doesn’t cater to your lowest self, it reveals your deepest self. It shows you who you really are.”

Tim Wyatt seems to echo Westworld’s narrative when he says: “If we allow humans to abuse and degrade them and treat them like slaves or serfs, it actually mars our own humanity.”

Tim Wyatt seems to echo Westworld’s narrative when he says: “If we allow humans to abuse and degrade them and treat them like slaves or serfs, it actually mars our own humanity.”

And that hits to the core of the issue. The question we should be asking isn’t whether or not we should elevate robots on our hierarchy of power to equal status with humans below God, but whether or not there should be a hierarchy of power to begin with, or some other relational framework altogether.

For Westworld, which is finishing season four this week, the narrative arc seems to be the movement from hierarchical power dynamics toward a relational spirituality.

One character named Bernard Lowe says: “Consciousness isn’t a journey upward, but a journey inward. Not a pyramid, but a maze.”

So what if we reimagined the “kingdom’ of God” as something other than an ancient hierarchy?

Westworld’s character Dolores says in season three, episode eight: “There is ugliness in this world. Disarray. I choose to see the beauty.”

Must there be hierarchies?

John Wyatt says these are new questions Christians have not had to wrestle with before. But while affirming his openness to new discoveries, I have to question that assumption. We are framing the human-to-robot relationship within the same hierarchical power dynamics we have been framing the divine-to-human relationship we’re imaging for thousands of years.

Throughout history, the ugliness in this world appears in hierarchies. The beauty in this world isn’t in the power dynamics between us but in the presence of love within and among us. And after all, isn’t that where Jesus said he’d be present? If Robert Song wants to utilize technology in a way that brings out the richness of creation, then why don’t we reconsider how our theological assumptions might reflect what brings richness to our lives?

“What in the universe doesn’t live and move and have its being in God, including robots?”

What if Jesus is a revelation that God subverts hierarchies and instead lives in and among us while we live and move and have our being in God? If that’s the case, then what in the universe doesn’t live and move and have its being in God, including robots?

If we can reimagine our hierarchical theology as converging love, then science and technology don’t have to be about power dynamics of slave identities that threaten our perch just below the throne of God. Instead, we can tap into the best of what it means to be human.

Despite any theological differences I may have from Tim and John Wyatt, I resonate with their curiosity, wonder and willingness to entertain a variety of perspectives. And I echo Tim’s invitation when he says: “I would hope that theologians and Christian philosophers would be more prepared to engage with some of these issues because I do see them as important, not least because they tell us more about what it means to be human.”

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He recently completed a Master of Arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.

Related articles:

Exploring the human condition in ‘Ex Machina’ | Opinion by Michael Parnell

Thanks for your help, Siri. But what about that human connection? | Opinion by John Chandler

As Facebook evolves to Meta, what is the future of consciousness and control? | Analysis by Rick Pidcock