Gen Z is a post-Purity Movement generation, having barely escaped the doling out of purity rings. However, exemplified by the popularity of “Virginity Rocks” T-shirts and regalia, this does not mean sentiments of purity culture never impacted our cohort of religious young people.

The Purity Movement is an evangelical ideological phenomenon that began in the 1990s with programs like True Love Waits. It is known for promoting teachings centered around sexual abstinence prior to heterosexual marriage, emphasizing how this discipline should be used to attain closeness with God among all Christians. “Purity culture” is a general term often used to describe the subsequent lifestyles Christians engage in because of these teachings.

A purity ring for girls currently for sale on Amazon.

Many Christians are familiar with the Purity Movement, and although Lifeway’s True Love Waits product line is still being produced for teens today, purity culture looks much different than it did for previous generational cohorts.

For my senior thesis as a religious studies major at Wingate University, I wrote a research paper analyzing the history of these teachings. With this paper, I asked two questions: How has the Purity Movement impacted the lives of women, girls, men and boys differently? How have the Purity Movement’s teachings affected how Christians read and interpret the Bible?

For my honors research project, I extended this research a bit further, attempting to contribute something new to undergraduate studies relating to purity culture. I wanted to know what current college students remembered from their adolescence surrounding purity culture and if they are still affected by religious feelings of shame during their current adult relationships.

But before I present my data, allow me to set the scene for the modern evangelical Purity Movement: Where it came from, where it has been and where it seems to be going.

Sexual purity in the evangelical church

Teachings promoting premarital sexual abstinence existed prior to the 1990s but were popularized in Christian culture by the growing commercialization of the Purity Movement among evangelical Christianity.

My research of premarital abstinence and sexual expectations began with a study of literature from the 1960s called “sex manuals.”

(Shutterstock)

“Sex manuals” were distributed to women and girls and described when and how to engage in sexual activities, sometimes being used in sexual education curriculums and other times being marketed as booklets available for women to purchase. They instructed females on the proper and improper ways in which they should sexually please their husbands and were notorious for their instructions on sexual submission.

For example, here is a quote from a textbook called Home Economics (1963) written by a woman for young women on what to do in the bedroom while getting ready for sleep:

In all things be led by your husband’s wishes; do not pressure him to stimulate intimacy. Should your husband suggest congress, then agree humbly all the while being mindful that a man’s satisfaction is more important than a woman’s. When he reaches his moment of fulfillment, a small moan from yourself is encouraging to him and quite sufficient to indicate any enjoyment that you may have had. Should your husband suggest any of the more unusual practices, be obedient and uncomplaining but register any reluctance by remaining silent.

Unsurprisingly, the Purity Movement in the 1990s and early 2000s did not distribute “sex manuals” that included such explicitly shocking teachings to students in youth groups. However, books written by popular evangelists mimicked the same teachings with a more Christian flair. These books were more conversational, coming from the perspective of a minister giving advice to his readers on how he thinks God wants sex to occur within a marriage. Themes of submission were still very prominent in these texts, but posed as spiritual roles and responsibilities, not just gendered expectations.

For example, Emerson Eggerichs in his book Love and Respect: The Love She Most Desires; the Respect He Desperately Needs (2004) teaches readers that women and men have fundamentally different desires. For men, he says those desires are sexual, and for women, they are emotional.

For example, Emerson Eggerichs in his book Love and Respect: The Love She Most Desires; the Respect He Desperately Needs (2004) teaches readers that women and men have fundamentally different desires. For men, he says those desires are sexual, and for women, they are emotional.

He cites Matthew 5:28, in which Jesus discusses lust as a form of adultery among men as biblical evidence of this. “Our Lord,” he says, “understood that men are stimulated visually. Sex is the forefront of a man’s consciousness.”

In the next paragraph, he discusses the contrasting roles of husband and wife, given this sexual focus among males.

“A wife longs to receive her husband’s closeness, openness and understanding. You can achieve this in two ways: (1) do your best to give him the sexual release he needs, even if on some occasions you aren’t ‘in the mood,’ or (2) let him know you are trying to comprehend that he is tempted sexually in ways you don’t understand.”

Love and Respect and similar books present the same ideas that the sex manuals did, but in an evangelical package: Men have uncontrollable sexual desires and their wives are responsible for regulating them.

From Purity Movement to purity culture

Today, the purity culture is less explicitly present in evangelical churches, as its teachings have bled throughout the widespread culture of the church. This has created a culture less defined by specific organizations that promote abstinence and instead characterized by the ways in which teachings, sermons and general conversations about sex center around feminine virginal purity and masculine sexual desire.

Modern versions of sex manuals are intertwined within the broad spectrum of Christian media. Abstinence is a theme in Christian movies, books, podcasts, blogs, Instagram posts, Twitter threads and even TikToks.

However, there is not one consistent message, as there was during the Purity Movement. My generation likely experienced some of the last youth groups that distributed purity rings or had the girls sign Sexual Behavior Contracts when the Purity Movement was phasing out of popularity.

“My generation also did not get ‘the talk’ about sex in a direct way. We got analogies, metaphors and object lessons.”

But my generation also did not get “the talk” about sex in a direct way. We got analogies, metaphors and object lessons.

Many of today’s generation of young Christians have experienced a more subtle version of the Purity Movement — a purity culture — with the same theologies and ideologies, just intertwined into broader church teachings rather than explicit initiatives or instructions. In fact, most Gen Z Christians I surveyed can recall lessons about sex during church, but not many heard their pastor or parent say the word “sex” out loud until adulthood.

The survey

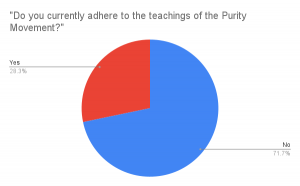

Although the influences of the Purity Movement are still prevalent in church life today, Gen Z believers are resisting the trends of shame that have deeply impacted the church they grew up in.

In an anonymous survey, 46 Wingate students answered questions about the shame they felt related to the sentiments of the Purity Movement and their sex lives. Although this is a relatively small sample size, participants answered a long survey in which I was able to collect various types of information.

Participants were asked to measure how often they felt shame during different sexual activities, answering for both their adolescent and current selves. Then, participants were asked to reflect on what they have been taught about the morality of sex throughout their lives, explaining how those morals were taught and how those teachings made them feel.

Demographics

- 35 women (76.1%) and 10 men (21.7%) participated.

- 35 (76.1%) identified as heterosexual, two (4.3%) identified as lesbian, eight (17.4%) identified as bisexual, and one (2.2%) listed their sexuality as “I don’t know.”

- Most survey participants identified as “Christian” (30), including one respondent from the Church of England, and three who identified as Catholic.

- Other than Christianity, there were four atheists, three “nones,” two agnostics, two Pagans, two people identifying as “spiritual,” and one Jewish respondent.

Initial impressions

Asked to reflect on their childhood or adolescence:

- 9% of participants reported that they, at some point, identified as an “evangelical,” but this percentage dropped to 45.7% when participants were asked if they still maintained this affiliation.

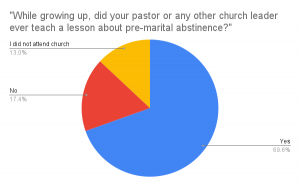

- 6% of respondents said a “pastor or any other church leader” had ever taught them a lesson about premarital abstinence.

- The same share of respondents said a parent had ever taught them a lesson about premarital abstinence.

- This number spiked when participants were asked, “While growing up, did any other adult ever teach you a lesson about premarital abstinence?” 80.4% of respondents reported having learned about premarital abstinence at some point during their childhood or adolescence outside of their home or church.

This indicates that sentiments of premarital abstinence have become immersed into other aspects of society. For example, some respondents explained their first exposure to premarital abstinence as a value was during sex education courses at public school.

Differences between childhood and adolescence

The second and third sections of the survey asked respondents to reflect on how often they felt shame when engaging in sexual activities during both adolescence and adulthood. The same set of questions were asked for each age distinction, and respondents rated themselves on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 meaning inapplicable, 1 meaning never and 10 meaning always.

Listed below are all the questions. While taking the survey, the adolescent and adulthood questions were separated into two sections, so participants could answer all the adolescent questions, then move on to the adulthood questions.

- During adolescence, how often did you feel shame during conversations about sex? Currently, how often do you feel shame during conversations about sex?

- During adolescence, how often did you feel shame while feeling sexual desire that you did NOT act upon? Currently, how often do you feel shame while feeling sexual desire that you do NOT act upon?

- During adolescence, how often did you feel shame while engaging in personal sexual activities, such as masturbating, watching porn or fantasizing about sex? Currently, how often do you feel shame while engaging in personal sexual activities, such as masturbating, watching porn or fantasizing about sex?

- During adolescence, how often did you feel shame while engaging in sexual activities with a person of the opposite gender, such as kissing, touching or sending nude photos? Currently, how often do you feel shame while engaging in sexual activities with a person of the opposite gender, such as kissing, touching or sending nude photos?

- During adolescence, how often did you feel shame while engaging in sex with a person of the opposite gender? Currently, how often do you feel shame while engaging in sex with a person of the opposite gender?

- During adolescence, how often did you feel shame while engaging in sex with a person of the same gender? Currently, how often do you feel shame while engaging in sex with a person of the same gender?

When reflecting on adolescent sexual experiences, for all questions, a majority of the respondents recalled feeling shame 50% to 100% of the time while engaging in the indicated sexual activities:

- During conversations about sex, 26.1% of respondents felt shame 90% to 100% of the time.

- The same intensity of shame was felt during adolescent feelings of sexual desires that were not acted upon.

- 37% of respondents felt shame 90% to 100% of the time “while engaging in personal sexual activities,” the highest amount of shame recorded of any question on the survey.

However, there was a stark contrast between their levels of shame in adolescence and adulthood. It seems Gen Z, only a few years removed from high school, has been able to quickly acknowledge and start processing feelings of shame related to sexual intimacy, even when they maintain their Christian faith.

Current attitudes

When reflecting on current sexual experiences, for all the questions, a majority of the respondents recalled feeling shame less than half the time while engaging in the indicated sexual activities.

In comparison, for conversations about sex:

- 0 respondents felt shame during conversations about sex 90% to 100% of the time.

- 4% of respondents reported conversations about sex only invoked feelings of shame 50% to 60% of the time.

- 1% said they felt shame only 10% to 20% of the time during conversations about sex.

Other notable responses indicated that:

- For sexual desires they did not act upon, only three respondents (6.5%) stated they felt shame 90% to 100% of the time.

- While engaging in personal sexual activities, only seven respondents (15.2%) felt shame 90% to 100% of the time.

- Only five (11.3%) respondents feel shame while having sex with a person of the opposite gender 90% to 100% of the time.

- Only six (13.6%) respondents felt shame during sex with a person of the same gender.

This research indicates that levels of shame related to sexual activities seem to have drastically decreased for Gen Z in the few years since we left high school, although Gen Z has not forgotten about the influence purity culture had on their upbringing.

This research indicates that levels of shame related to sexual activities seem to have drastically decreased for Gen Z in the few years since we left high school, although Gen Z has not forgotten about the influence purity culture had on their upbringing.

Although there are some members of Gen Z who still experience great amounts of shame related to sexual activities post-Purity Movement, no part of the survey indicated they felt nearly as much shame during sexual activities as they recalled feeling during adolescence.

Church teachings and shame today

During the last section of the survey, the long response section, respondents explained the ways in which church teachings influenced their perceptions of sex. They also discussed how they are overcoming feelings of shame and learning how to have healthy sex lives that are congruent with their beliefs in Christianity.

Here are some notable things respondents had to say.

Most respondents explained their experiences of sex education by recalling analogies or metaphors, rather than explicit conversations about sex.

Participants felt these object lessons, although clearly about sex and talked about in the church, left them uncomfortable when they had questions about sexual encounters or experiences. Respondents felt this way of teaching about sex made it clear that open conversations about sex were not welcome in church environments.

Some examples:

- “I had heard the super common ‘tape’ analogy before. … There was no outright condemnation of sex; it was more subtle, passive-aggressive comments, looks and phrases that I think worked their way deeper into my head than outright dialogue would have.”

- “In middle school, the sex educator brought a teacup and had students write nice things about (it). The teacup was then dropped and shattered. … It described how women’s bodies are like this tea cup (precious) and then sex (dropping the teacup) ruins the purity of women.”

- “Girls were taught the analogy of a piece of paper being crumpled up and then opened up again, and how no matter how hard you try to make the paper perfect again it’ll always be damaged.”

Some respondents explained they were conflicted about their feelings on sex, largely due to the ways in which the church taught about sexual purity.

They disliked the gendered expectations promoted by their churches growing up, yet felt shame when they tried to explore their sexualities outside these teachings (despite openly disliking them). For some respondents, abstinence was still a goal, but as a personal faith choice, not as a means to fit into church culture.

Examples:

- “I always correlated sex and sexual acts with shame, and doing them before marriage made me feel like a bad person and a dirty person. This was a result of the teachings I had learned growing up and it was always targeted toward women about how they needed to be pure for their husbands, but the opposite was never taught that men should be pure for their wives, so it seemed one-sided.”

- Premarital abstinence itself “is a great teaching. It was the shame that then followed that put fear in me to have thoughts or partake in any physical action or attraction.”

Finally, it seems respondents are using their resources at college, on social media and in their social lives to learn more healthy perspectives on sex. Although they are not abandoning their beliefs in Christianity, they are broadening their perspectives on how sentiments of sexual purity should (or should not) fit into their personal lives.

Examples:

- “I have both a positive and negative perception of sex now. I was in a long-term relationship where I did things sexually that I now realize I shouldn’t have had to do and weren’t normal because I wanted the man to be sexually satisfied. Being in a different relationship now, I can see how pleasurable sex can be and it is not just about pleasing the man; women can have pleasurable sexual experiences too. However, I also know I would be judged by people (parents, church members, etc.) if I said that.”

- “After leaving the church after high school, I felt much less shame about my sexuality. A lot of YouTubers, influencers, podcasts, etc., talked about sex very openly and casually and helped me learn that I held sex to an extremely high standard.”

So, Gen Z’s experience with purity culture included plenty of teachings that commodified their bodies but did not foster deep conversations about sex, desire or sexual feelings, as analogies and metaphors talked about sex in terms of objects, not humans. And for Gen Z, this shift seems to be fostering a better understanding of consent and health, as well as a desire to do better when it comes to conversations about sex, or having sex, that may not have been present in previous discussions on sex.

Mallory Challis

Mallory Challis is a graduate of Wingate University who will begin master of divinity studies at Wake Forest University School of Divinity this fall. This summer, she is serving as an intern at Providence Baptist Church in Charlotte, N.C. She is a former BNG Clemons Fellow.

Related articles:

My journey through purity culture and Christian worship music | Analysis by Rick Pidcock

‘Please, think of the kittens’ and other scary things I learned from purity culture | Opinion by Amy Hayes

They grew up in purity culture, then taught it and now want to help others recover from it