Once again, I’m so grateful I live in Oregon.

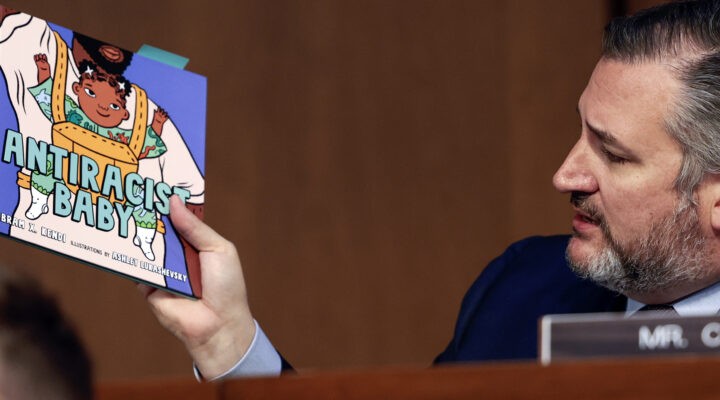

Across conservative states, legislators are interfering with what’s taught in K-12, colleges, universities and workplaces. They’ve targeted content that addresses issues of race, gender and sexuality, with a special emphasis on Critical Race Theory and intersectionality.

They argue they are ensuring that students (read straight white male students) are not made to feel “discomfort” because they are told they are inherently racist or sexist. They claim that attention to race and gender is “divisive” because it calls attention to racial difference rather than colorblindness. Sexuality content, they argue, is “normalizing” and “grooming” for queerness.

Susan Shaw

They are attempting to put in place laws that would remove gender, race and sexuality content from classrooms and libraries and prohibit institutions from requiring staff to participate in diversity-focused trainings.

Here’s my experience

I’m a professor of women, gender and sexuality studies, known as WGSS. For six years, I directed Oregon State University’s Difference, Power and Discrimination Program, a faculty development program that teaches instructors how to center issues of diversity, power and systemic discrimination across disciplines. I’ve led workshops for faculty and staff at institutions across the country using intersectional, feminist, critical race and queer theories to examine how structures of power shape academia, how systemic discrimination works in higher education, and how we can transform curriculum and institutional structures to create more inclusive, equitable and just colleges and universities.

Republican legislators really are clueless about what this work is.

With little knowledge of the theories, research or processes of socially transformative curricula, these legislators have twisted, misinformed and lied to score political points by playing on the fears of white people, particularly white men, about the loss of social power.

So from the perspective of someone who has spent a 35-year career so far doing this work, let me explain what really happens in social justice-focused teaching.

Feminist teaching and learning

No teaching is value free or morally neutral. In WGSS, we acknowledge and own the political nature of our discipline, and we work intentionally to shape our classrooms to reflect our political goals of inclusion, equity and justice.

“I welcome and care about every student in my class, including the straight white men.”

That means I try to create a classroom that is itself inclusive, equitable and just. I welcome and care about every student in my class, including the straight white men, and I also recognize the ways that experiences of mistreatment, discrimination and oppression affect students’ lives and the selves they bring to the classroom. I pay attention to dynamics of difference and power in my classroom, and I help students learn to analyze the structures of discrimination in their lives and in society.

Feminist teaching trusts students as learners and co-teachers. In the feminist classroom, teachers do not simply bring content and pour it into students’ heads as if they are empty receptacles. Rather, we approach teaching as a way we all, students and teacher alike, construct knowledge together, and we maintain that we all learn more when everyone brings something to the discussion.

We also prioritize critical thinking, particularly from intersectional feminist, critical race and queer perspectives. Across the university, much teaching still relies on content shaped by and for straight white men. So, for example, we learn the histories of war but not the histories of reproductive justice. We study scientific research methods without asking who created those methods, why and whose interests they serve. WGSS seeks to bring marginalized experiences, perspectives and methods to the table to challenge students to think more deeply about the hows and whys of important contemporary topics.

We don’t tell students what to think. A faculty colleague once wisely quipped that we couldn’t possibly brainwash our students; we can’t even get them to read the syllabus. Our goal is for students to think for themselves.

Discomfort isn’t bad

Do we make them uncomfortable? I certainly hope so.

The deepest learning occurs when we are out of our comfort zones. That’s part of the reason I love taking students on study abroad trips so much. When we hear or experience something new, we are uncomfortable as we figure out how to make sense of it.

“The deepest learning occurs when we are out of our comfort zones.”

Discomfort in education is not a bad thing at all. With discomfort, however, feminist teachers also work intentionally to create a classroom space that is open, honest, welcoming and supportive, as well as challenging. It’s a place where students can make mistakes with what they say, and we don’t call them out, but, as feminist activist Loretta Ross says, we call them in. It’s a place where students can disagree — with one another or the professor — respectfully.

Feminist teaching values each person and the unique experiences that person brings to the classroom. Everyone has something to contribute to the knowledge we’re creating together. Conservative students are welcome to participate in that process. They may be challenged, but, as long as the challenge is civil, that’s part of the learning process. And they are welcome to challenge me or other students.

The problem is that sometimes students want to say things with no accountability for their words. Critique is a key part of education, and students need to be open to having their ideas challenged. Students also have to understand that what we’re critiquing is ideas not people.

“Critique is a key part of education, and students need to be open to having their ideas challenged.”

While feminist teaching is deeply concerned about the individual student in the classroom, our content centers on systems of oppression and structural inequities. We understand our students as people within a web of relationships, institutions and ideologies that shape identities and experiences. We also know that social transformation is much less about changing individual hearts and minds than about transforming social structures.

Diversity Academy

In addition to teaching at OSU, I also have spent a decade facilitating a summer “Diversity Academy” at another university in California. Faculty and staff spend eight six-hour days with me learning about how they can center issues of social power, diversity and institutional structure in their work, whether that’s as a professor, administrator, maintenance worker or financial aid officer.

We start the academy with an overview of systems of oppression theories. These theories work to explain the persistence of interlocking systems of sexism, racism, heterosexism, classism, ableism and ageism. We ask how these systems are at work at their university and in their unit. We talk about the consequences of these systems, and we identify ways each person can make change toward greater inclusion, equity and justice within their sphere of influence.

Do I tell them people are born inherently racist or sexist? Do I make the white people feel guilty? Do I make individuals responsible for racism, sexism and so on?

Of course not.

In fact, what I tell them is that we learn prejudice and discrimination because we all are born into racist, sexist, ableist systems. The problem, I explain, is not individuals; the problem is the system. Guilt, I argue, is counterproductive because it re-centers the individual rather than addressing structural problems. I also tell them that racism, sexism, classism and so on are harmful to everybody — to different degrees and in different ways, of course, but everyone suffers in systems of oppression because something of one’s humanity is lost when they participate in harming others.

“The problem, I explain, is not individuals; the problem is the system.”

I don’t end there, though. I go on to what Latina theologian Ada Maria Isasi Dias called a hopeful utopian vision — a dream of what could be in a world that is inclusive, equitable and just. We imagine a transformed world and brainstorm how we could get there. And I contextualize all this within a central principle — love, a radical love that embraces the humanity of all of us and challenges us all to do better so that everyone can have enough food and shelter and health care and agency, enough affirmation, enough belonging, enough love.

The love of power

This work that I and others like me do is all so scary to Republican legislators that they have to lie and misrepresent social justice teaching. They pick and choose from occasional mistakes social justice educators may make (myself included); they use scare tactics to enlist voters against the very kinds of education that would most benefit many of the poor and working-class whites who are part of the Republican base.

Why? They’re afraid of losing power. They are the beneficiaries of a system that pretends to be colorblind while systematically and disproportionately incarcerating young Black women and men. They benefit economically when poor and working-class whites find greater solidarity with rich white Republican legislators who exploit their labor for their own gain instead of with Black people, indigenous people and persons of color, women and queer people who also face systemic exploitation.

“They use scare tactics to enlist voters against the very kinds of education that would most benefit many of the poor and working-class whites who are part of the Republican base.”

What they love is power. This was clear during the attempt to overturn the 2020 presidential election. No principles of truth, democracy, law and order, morality or any other lofty ideal underlay the blatant attempted power-grab. The love of power was more compelling than love of country, love of democracy or love of truth. And that continues to be so.

Lovers of power seek to hold onto power no matter the cost to others or the unethical methods they must employ to do so. Social justice teaching provides them with the perfect scapegoat and means to manipulate their base by playing on fears of the loss of white power.

Social justice teaching is a threat to them because it seeks to make unequal power visible and to redistribute power to create equity and justice for all people.

Having done the work of social justice teaching my entire career, I know its transformative potential. Many of my students do change as they encounter, construct and grapple with feminist knowledge. They catch a vision of what could be, and they develop skills to make a difference for good where they are. Even the students who disagree with every word I say leave my classroom with a different appreciation for feminist teaching and learning, and they know their teacher cared for them and welcomed them, despite our differences.

If Republican legislators prevail, many students across the nation will not experience the joy of confronting new, disruptive, life-changing ideas. That will be a loss for them and a loss for our country and our world.

Susan M. Shaw is professor of women, gender and sexuality studies at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Ore. She also is an ordained Baptist minister and holds master’s and doctoral degrees from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Her most recent book is Intersectional Theology: An Introductory Guide, co-authored with Grace Ji-Sun Kim.

Related articles:

Critical Race Theory, voter suppression and historical negation: The irony of it all | Opinion by Bill Leonard

It’s time to stop the insanity that is killing public education | Opinion by Mark Wingfield