The July issue of Sojourners magazine included “A Christian Call for Reparations” by Kelly Brown Douglas, dean of Episcopal Divinity School at Union Theological Seminary and canon theologian at the Washington National Cathedral.

Kelly Brown Douglas

Douglas’ call for reparations echoed the voice of the late James Foreman who in 1969 famously disrupted a service at the Riverside Church in New York City to issue his Black Manifesto, requesting $500 million from white Christian and Jewish congregations who aid and abet the “exploitation of colored peoples around the world.”

Douglas’ contemporary call joins a plethora of more recent proposals for public reparations including Ta Nehisis Coats’ “Case for Reparations,” as well Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee’s H.R 40, which proposes a commission to study and issue proposals for governmental reparations. Last month the city of Asheville, N.C., approved a reparations initiative.

While the debate over public reparations has been pushed forward by cities like Asheville, individual institutions also may participate in this work.

Numerous colleges and universities have completed self-studies in recent years in an attempt face their complicity with the institution of slavery. Last year, Princeton Theological Seminary and Virginia Theological Seminary announced that they would establish endowments as a form of reparations that would among other things fund scholarships for descendants of slaves.

Institutions and churches studying their past

Beyond educational institutions, the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, too, is currently studying its complicity in racism and white supremacy over the course of its 20th century history.

What is to prohibit local congregations from doing the same thing?

Douglas paints a picture of what reparations should look like for Christian congregations. They must serve as a means of “truth-telling” — a form of remembrance — to identify how systems and institutions were created and undergirded by white supremacy. Many congregations neglect their own institutional histories, which blinds them to ways in which they have failed to live up to their confessional beliefs.

Reparations, she suggests, must both foster the formation of a collective moral identity and serve as the present work of the church and not some work for a distant eschatological future.

For Christian congregations, both those inside and outside the free church tradition, it is easy to think that the work of reparations is the work of larger denominational structures. Such an idea, however, merely shirks the responsibility of racial justice from one institutional body to another.

One church’s example

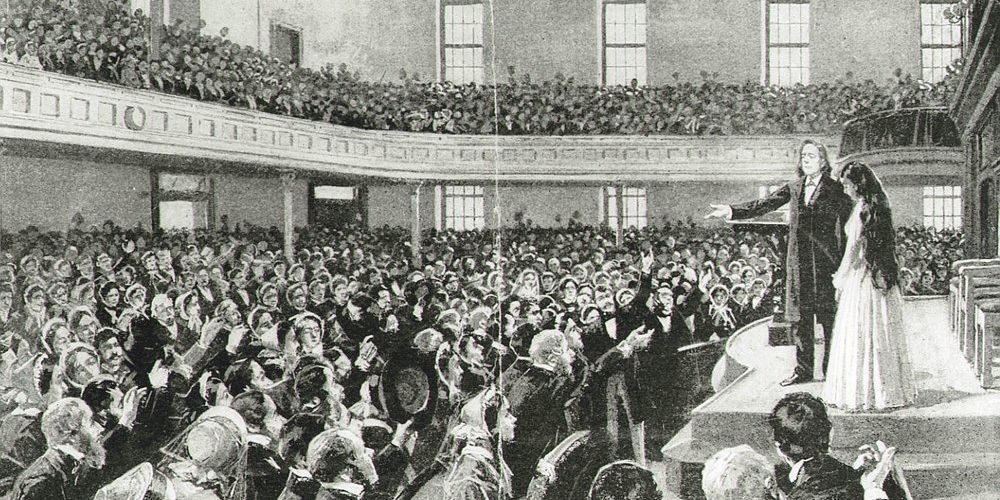

Beginning in 2018, the First Church in Cambridge, Mass., modeled what the work of reparations might look like in a local church through a Louisville Institute-funded project titled, “Remembrance and Reparation at First Church.”

First Church, Cambridge, Mass.

The congregation, which dates to 1636, studied its history with regard to slavery and race in the context of Colonial Massachusetts. Led by Pastors Dan Smith and David Kidder, the church studied the congregation’s minutes, identifying how the church treated Black and indigenous persons of color who sought membership. They studied how ministerial leadership addressed questions of slavery and whether or not they themselves owned slaves.

The historical study found the congregation was “slow to address the challenges of abolition and a growing Massachusetts population of free Black persons.” Even as Northern opinions regarding slavery began to change, “Black families found more welcoming options in the growing number of predominantly Black churches in New England.”

Following this historical work of remembrance, in 2019, the congregation turned toward studying the matter of reparations. They studied the theological and biblical basis for which a congregation might participate in the work of reparations. Pastors Smith and Kidder led the congregation in discussions regarding national and public reparations.

First Church encouraged individuals to take a personal reparations pledge with the organization FOR Truth and Reparations, a grassroots organization dedicated to encouraging “individuals, businesses and institutions of moral conscience to reflect on their unfair advantages and do their part in redistributing value to people who have less because of generations of structural discrimination and political inequality.”

In June 2020, First Church adopted a statement on “Becoming an Anti-Racist Church,” and their work is ongoing. In their statement, they acknowledged “the problem of racism is a white person’s problem and that this is white people’s work.” The work is both personal and communal.

Now is a time for concrete action

While the attention of many Americans is currently focused on Black Lives Matter, now is an opportune time for local congregations to consider taking up the work of reparations.

Keeping in mind Douglas’ plea that the work of reparations must function as a remembrance of past injustices, foster a collective moral identity, and take place now, there are many avenues congregations might take in this work.

James W. Goolsby Jr., senior pastor of First Baptist Church, and Scott Dickison, senior pastor of First Baptist Church of Christ, have worked together in Macon, Ga., to find a way the congregations, with a tangled history embedded in racism, could become friends. (AP Photo/Branden Camp)

All these avenues, however, require unearthing histories that often have gone untold. The first task congregations must engage in is coming to terms with their history. Such work is long and difficult, and most churches do a poor job keeping up with their history. Those who do, often remember only a positive and optimistic history.

For churches to effectively engage this work much like First Church in Cambridge, it may be necessary to appoint a committee or task force to study the congregation’s history with a particular focus on white supremacy and racism.

Yes, committee work is tedious and boring and not altogether immediate, but as Douglas notes, the project of reparations requires remembering so as to better foster a collective moral identity. Identifying and remembering the moral failures of how your spiritual home has been complicit in systems of white supremacy (and it has) is important in this process.

Questions to consider

The work of such a “Committee on Reparations” may take many forms, and, as organizations like BJC show, slavery is not the only moral failure with regard to race that may necessitate the formation of such a committee. Congregations might begin by working through some of the following questions.

- Were slaves and those who claimed ownership of them members of your congregation in the 19th century?

- Were Black individuals prohibited from joining your congregation during the era of Jim Crow?

- Is there a historically Black congregation that shares your white congregation’s name or down the street from your congregation?

- Were members of the Ku Klux Klan also members of your congregation?

- Did your congregation hear support for slavery from the pulpit? Colonization? States’ rights? Segregation? “Law and order?”

- Was your congregation part of, or did it support, denominational entities that advocated slavery, resisted civil rights, or generally avoided issues of racial injustice?

- Did your congregation flee its downtown location when white families fled to the suburbs to escape Black families moving into the neighborhood?

- Did your congregation grow and profit from white flight to the suburbs?

- Did your congregation remain silent about the civil rights movement?

- Did your congregation oppose integration?

- Did your congregation support a one-sided form of integration that destroyed a legacy of Black education, firing Black teachers and administrators, allowing Black children to attend white schools without a support system?

- Have your congregation’s longest-running ministries avoided issues of racial inequality and white supremacy?

- Did your congregation passively allow the passage of racist policies that disadvantage Black homeowners in your community?

While not an exhaustive list, answering yes to any of these questions is a good indication that the work of reparations for racial injustice is work for your congregation. If this historical work seems daunting, contact a historian in your area to see if they might be willing to help.

This history is not easy or pretty, but it is necessary for Christian congregations to uncover and take responsibility. This work will not likely be a year-long process that ends in a lump-sum donation. It will likely be years-long work that hopefully reshapes and guides your congregation’s financial and ministerial priorities for decades to come.

As James Baldwin noted, and Eddie Glaude highlights in his recent work, Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons For our Own, “Responsibility can’t be lost, it can only be abdicated. If one refuses abdication, one begins again.”

It is long past time for religious congregations to begin again — to dredge up their history in order to confront it and begin anew. Congregations cannot begin to move forward with the work of racial justice until they face their past complicity in white supremacy.

Andrew Gardner holds a Ph.D. in American religious history and is the author of Reimagining Zion: A History of the Alliance of Baptists (2015).

Related articles:

5 reasons why reparations talk makes white people crazy

Princeton Seminary’s gift of reparations? Let’s talk instead about cultural competency