Earlier this month, I wrote about the history of the subminimum wage and a current lawsuit seeking to overturn it as part of the ongoing economic struggle for equality. In the sobering spirit of Lent, this follow-up piece turns from the historical and legal dimensions of wage justice to the rhetorical, examining how corporations favorably frame their treatment of their low-wage employees.

The fight for equality is a war of words as much as a war of ideologies.

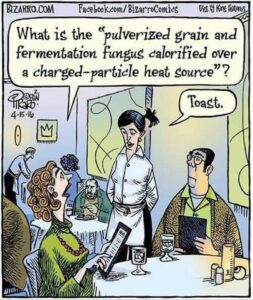

Credit: Don Piraro, www.bizarro.com.

One of the reasons more of us do not know about the inhumane impacts of policies like the subminimum wage is that corporate PR minimizes them. It is a strategy that works much like a cartoon Dan Piraro created a few years ago. The scene is an upscale restaurant. A nicely dressed woman, seated at table, asks the server a question about the menu. “What is pulverized grain and fermentation fungus calorified over a charged-particle heat source?” The server responds, “Toast.”

Piraro’s cartoon pushes the use of grandiose descriptive language to an extreme, but the joke wouldn’t work if this device wasn’t familiar to us. We can (and should) laugh at this type of preposterous exaggeration. But we should not simply dismiss it.

Such elaborate descriptors are more than pretentious. There is a sinister undercurrent to this use of language. Wording a menu to make ordinary toast sound exotic and refined is both deceptive and manipulative, giving the illusion that something meager is something special when nothing could be further from the truth.

Similarly, many corporations have taken to giving employees long or grandiose job titles. Apple refers to its retail associates as “geniuses.” Kate Spade’s sales staff are “muses.” At Sephora, they are “cast members.”

These titles give the impression that these employees are special, that the companies value them more than they do. If corporations truly valued their rank-and-file workers, no one in America would be working for less than a living wage. Unfortunately (from the perspective of corporate boards), living wages diminish company profits and therefore executive bonuses. It’s better for the bottom line for corporations to give the appearance that employees are special and well taken care of without actually delivering — the HR equivalent of offering toast as “calorified, pulverized grain and fermentation fungus.”

Giant corporate entities such as Darden Inc., the restaurant conglomerate that is the subject of One Fair Wage’s subminimum wage lawsuit, are particularly adept at casting such smokescreens because they can afford the services of marketing firms and lobbying groups that specialize in these sorts of effects. Visit Darden’s website and it appears their restaurant employees have it made. In March 2021, the company declared it would ensure all employees made a minimum of $10 per hour. They also state that, across all their brands, Darden servers earn an average hourly rate of $22.47.

The Darden website further advertises generous benefits for team members including (a) access to health benefits, (b) paid sick leave, (c) paid family and medical leave, (d) 401(k) savings opportunities, (e) a stock purchase plan, (f) an employee assistance program, and (g) dining discounts. It all looks and sounds fantastic.

“There is a glaring asterisk accompanying Darden’s hourly rate claims for its servers.”

However, the smokescreen soon becomes apparent if we take the time to look closely at what Darden is presenting. If we wave a little math at it, the smoke quickly starts to dissipate.

For starters, there is a glaring asterisk accompanying Darden’s hourly rate claims for its servers. Both the $10 minimum and the $22.47 average wage rates are inclusive of tips. Since tips are variable by nature, Darden isn’t actually guaranteeing very much. They are assuming their servers will earn enough in gratuities to raise their effective pay to these advertised levels. Thanks to the subminimum wage, Darden itself pays these employees less than $3 per hour in most states. The rest (in the form of tips) comes from customers. That’s not much of an employee investment on Darden’s part.

Even if we give Darden the benefit of the doubt, $22.47 per hour isn’t much to brag about. It only sounds generous because this average rate is three times the pitifully, scandalously low $7.25 federal minimum wage. Assuming a full-time schedule of 40 hours per week (which few servers receive) and consistent tipping from customers, a Darden server could expect to gross an average of $3,595 per month or $43,142 per year. That amount falls below MIT’s “livable wage” projections for every state except Kentucky.

As an aside, the term “living wage” is another smokescreen that has become commonplace in our political discourse.

MIT – the university that developed and maintains the database(s) used to calculate what a living wage in each state would be each year – defines “living wage” as “the minimum income standard” required to stave off “the need to seek out public assistance or suffer consistent and severe housing and food insecurity.”

The research team behind the project states, “The tool does not include funds for pre-prepared meals or those eaten in restaurants. We do not add funds for entertainment, nor do we incorporate leisure time for unpaid vacations or holidays. Last, the calculated living wage does not provide a financial means to enable savings and investment or for the purchase of capital assets.” In other words, this supposed “living wage” is a survival wage, not a wage people can actually live and thrive on as the term implies.

“This supposed ‘living wage’ is a survival wage, not a wage people can actually live and thrive on as the term implies.”

These numbers, therefore, mislead the general public and severely underestimate what the true cost of living in the United States has become.

Thus it is even more scandalous that Darden then expects its servers to pay for many of their company “benefits” out of an already less-than-sufficient wage. Medical and dental insurance is offered through “a private health exchange,” but there is no mention of Darden covering a percentage of the cost. Darden will match employee contributions to a 401(K) savings plan up to 6%, but how much can a server contribute toward future retirement when they’re likely struggling to cover the costs of present needs? The same holds true for employee “opportunities” to fund Day Care Savings Accounts (FSAs) or Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) using their own pre-tax dollars, or the chance to purchase Darden stock at a 15% discount. As of this writing, shares of Darden Inc. are trading around $140 per share. Even at the reduced rate of $119, a Darden server earning the company’s average hourly rate would have to work six hours (15% of their weekly full-time schedule) to afford one share.

Developing eyes to recognize these smokescreens for what they are is essential if we desire to shape a more just and equitable society, if we are at all interested in God’s will being done on earth as it is in heaven.

The manipulative corporate framing of systemic realities is all around us. These frames contribute to the widening wealth and opportunity gaps in America as well as the crumbling of the American Dream. For decades, workers across the economic spectrum have seen their compensation stagnate even as their productivity has steadily increased. Meanwhile, executive bonuses and compensation packages for top executives have reached preposterous heights.

We can and should do better. These smokescreens not only obscure present realities, they also suffocate future possibilities.

May we who profess Jesus have eyes to see.

Todd Thomason is a gospel minister and justice advocate who has pastored churches in Virginia, Maryland, and Canada. He holds a doctor of ministry degree from the Candler School of Theology at Emory University and a master of divinity degree from the McAfee School of Theology at Mercer University. In addition to Baptist News Global, Todd writes regularly at viaexmachina.com. Follow him on Twitter @btoddthomason and Facebook @viaexmachina.

Related articles:

In this Lenten season, consider the plight of subminimum wage workers

The U.S. wealth gap presents both a political challenge and a spiritual problem | Analysis by Todd Thomason

The connection between the wealth gap, monopolies, affordable housing and biblical truths | Opinion by L.A. “Tony” Kovach

Think you understand what it’s like to live on minimum wage? Here’s my story | Opinion by Rick Picock

It is impossible to afford rent almost anywhere in the U.S. with a minimum-wage job