A plan to melt down and ultimately reuse the bronze from the Robert E. Lee statue that white supremacists violently rallied to save in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017 is an inherently spiritual undertaking that should appeal to many people of faith, according to a leader of the initiative.

“The goals of the project are to be transformative and to seek healing, which are are some of the central tenets of the Christian faith,” said Jalane Schmidt, an associate professor of religious studies at the University of Virginia and a steering committee member with Swords into Plowshares, a coalition spearheaded by the Jefferson School African American Heritage Society to use the bronze from the Lee monument, which was taken down in 2021, to create a new work of public art.

Jalane Schmidt

Schmidt, the daughter of a Mennonite pastor, explained the plan and its meaning in a May 9 webinar conversation with host and moderator Sam Heath, manager of the EJUSA Evangelical Network. Schmidt spoke about the historical research into the monument, the way it was used to perpetuate the Southern myth of the Lost Cause and how it stood as a symbol of oppression and intimidation for close to a century.

And she dispelled the lie inherent in the Lee monument and other Confederate statues, namely that they represent community history and values during and since the mid-19th century.

“In our community of Charlottesville and Albermarle County at the time of the Civil War, 52% of the population had been enslaved,” she said. “So, that’s over half of the residents of our community who were enslaved. What this said to me was: Those Confederate statues have been lying to us from day one because the majority of people here were elated with the victory of Union forces.”

Heath asked Schmidt to describe the difference between “history” and “memory” and how the distinction fits into the work of UVA’s Memory Project, which she directs as part of the university’s larger Democracy Initiative.

“History is the collection of events, facts and data which may or may not be preserved somewhere, whereas memory takes a portion of history that’s been deemed representative or sometimes reprehensible or sometimes laudatory and holds it up for our edification or sometimes as a cautionary tale,” she answered. “But memory prioritizes certain historical facts and says that ‘this is worthy of reflection.’”

An example is the Civil War, which represents a central place in American memory despite representing only four of the nation’s nearly 250-year history, Schmidt said.

A flatbed truck carries a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee away from the Market Street Park July 10, 2021, in Charlottesville, Virginia. (Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

“We take that and say this is so worthy of reflection that we’re going to focus on this and we’re going to make heroes of certain people … or say these people were really repressed by the Antebellum slave regime. … It’s about reflection on certain episodes of history that we have deemed worthy for an extra bit of our attention.”

But white supremacists historically have taken a very narrow portion of history to construct their Civil War memories, even though Gen. Lee himself was against such notions, she said.

“Lee became a paragon of honor among those who maintained the flame of this Lost Cause interpretation. … But Lee himself, after the war, was insistent there should not be memorials to the Confederacy. He was not buried in his uniform. There was no Confederate flag at his funeral. Nothing. Lee said we don’t want to keep this wound open. People who claim to be honoring Lee are disrespecting his express wish.”

Yet the movement continues, she said. “Part of what’s going on with the Confederate States of America is this attempted foundation of a white Republic. Explicitly so. And for these white supremacists who call themselves the Alt-Right, which is the same-old white supremacy gussied up in polo shirts and khaki pants, their explicit desire is to create a white ethno-state. They want there to be a kind of ethnic cleansing or a forced migration of the rest of us who aren’t deemed white. So Lee, for them, is a historical figure they’ve latched onto, especially the more Southern nationalist variety. They see in Lee a figure who was valorized by Confederates and their Lost Cause descendants.”

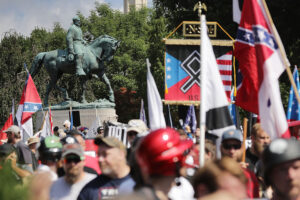

The statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee stands behind a crowd of hundreds of white nationalists, neo-Nazis and members of the “alt-right” during the “Unite the Right” rally August 12, 2017, in Charlottesville, Va. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

That’s why the Charlottesville City Council’s February 2017 decision to remove the Lee monument enraged the far right and motivated two days of violent rioting in the city the following August.

“What happened during the Trump campaign in 2016 is they came out from under their rocks,” she said. “They were emboldened. And they specifically said, when they came to Charlottesville, ‘We are here in support of Donald Trump’s agenda. He is our hero.’ They were wearing their MAGA hats as they came into the park.”

But the community was resolute in removing the statue because it wasn’t a fair representation of their collective history, Schmidt said. “It was saying that this narrative of the Lost Cause was always exclusive of a large part of our community … and there was a broader consensus that this is not what we want in our public space.”

The purpose of the Memory Project is to expand public knowledge about the community’s history, she added. “We are attempting to promote more inclusive narratives about our past, and we do that by sponsoring different art and performance initiatives, like Swords into Plowshares, and commemorative events and panel discussions.”

That’s where the plan to melt down the Lee statue comes into focus. The goal is to take community input on appropriate designs and ultimately commission an artist to use the bronze ingots to craft new public art for installation by 2026.

The entire process is designed to be socially and spiritually transformative, Schmidt said. “How do we take something that was harmful and turn it into something that gives healing and restoration? That’s a way of living our faith in the present day. I think it can be energizing and illustrative for a lot of projects we have going on in church and society.”

Related articles:

Of statues and stories: Reckoning with the Lost Cause | Opinion by Greg Garrett

Tearing down statues doesn’t erase history | Opinion by Ella Wall Prichard

At the intersection of Monument(s) and Avenue(s), a new vision rises | Analysis by Craig Martin