By Blake Tommey

Alan Bean and his wife Nancy had spent only a year in the small, panhandle town of Tulia, Texas, when the inconceivable happened—local police arrested 47 Tulia residents in pre-dawn raids in connection with an extensive criminal drug operation. “That is, according to the uncorroborated word of a single undercover agent,” Bean added. Nonetheless, the arrests resulted in 38 convictions for various drug charges with sentences of up to 99 years in prison.

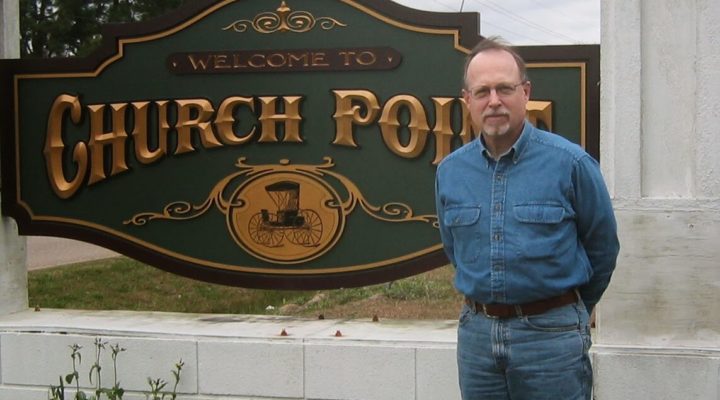

Alan Bean

The local press characterized the arrests as a triumphant stride in the fight to keep Tulia clean and virtuous. This troubled Bean, who began visiting the defendants’ families to learn more about the case. Each interview yielded more claims of innocence and confusion about why officers had arrested the defendants. Moreover, Bean explained, “It quickly became obvious that the defendants were all from Tulia’s black community on the southside of town; so, we started looking into the undercover officer.”

Tom Coleman, the undercover officer in Tulia who worked with the Panhandle Regional Narcotics Task Force, had a checkered past, including an arrest by a nearby sheriff and a $10,000 restitution payment due to Coleman’s failure to pay debts to local merchants. Bean soon discovered Coleman’s newest venture—profiting from reimbursement for drug buys, turning in little baggies of white powder, mostly baking soda, containing only small amounts of actual cocaine. “The problem is,” Bean said, “he was turning in cases of powdered cocaine from people who didn’t even know what powdered cocaine looked like.”

Alan Bean (second from left) and his ministry, Friends of Justice, was honored with CBF’s Emmanuel McCall Racial Justice Trailblazer Award at the 2019 General Assembly in Birmingham. Pictured left to right: Kasey Jones, CBF Associate Coordinator of Strategic Operations and Outreach; Alan Bean; Lydia Bean; Nancy Bean; CBF Executive Coordinator Paul Baxley; and Pan African Koinonia Steering Committee Members Carrie Tuning and J Livingston.

Bean, who was honored at the 2019 Cooperative Baptist Fellowship General Assembly as a recipient of CBF’s Emmanuel McCall Racial Justice Trailblazer Award and is now an experienced criminal justice advocate with his own nonprofit, Friends of Justice, said that exonerating wrongly-convicted folks like the Tulia defendants requires more than just facts. You must empower the wrongly-convicted with a compelling narrative that can compete with more socially-accepted narratives, often rooted in small-town racism or xenophobia, he added.

The Beans began reaching out to advocacy groups, pro bono attorneys and journalists, the three most important allies in narrative-based advocacy, explained Bean, who is a member of Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas. After three years, they had attracted attention from national news sources, such as the New York Times and ABC’s 20/20, as well as prominent pro bono attorneys. These partners and others helped the Beans chart a new narrative, in which ordinary citizens had been wrongly convicted by a corrupt and even racist law enforcement official.

Alan Bean stands with the ‘Jena Six,’ teenagers who were who were charged with attempted murder but who had simply been defending themselves amid ongoing racial tensions at school in Jena, Louisiana.

“Narratives have the unmistakable power to humanize people, even very broken and flawed people,” Bean said. “If you can place a person in a narrative world, you have something truly powerful. People can understand who they are, why everything happened as it did and how an innocent person was wrongfully prosecuted. You realize that this is a human being. You see this individual not as one of them, but as one of us. You associate your own brokenness with that person and extend them grace. But you have to find the strength of the story and pull people in.”

In April 2003, three years into the 38 sentences, Dallas Judge Ron Chapman held an evidentiary hearing, in which Coleman admitted to using racial epithets in casual conversation, and the judge ruled that Coleman was not a credible witness under oath. Judge Chapman vacated all 38 convictions and the state of Texas eventually paid around $6 million in reparations to the defendants.

But Alan and Nancy Bean had become pariahs in Tulia. Alan’s search for a new ministry position following the conclusion of the case turned up only hostility from local churches.

“What we had done was profoundly unpopular with middle-class, church-attending, upstanding citizens of the community,” Bean explained. “And even after our side was exonerated and everybody had been freed from prison, they were still angry at us for besmirching the community and standing up for people who ‘didn’t deserve it.’”

In Church Point, the real story began when young boys were spotted with white girlfriends and tension developed with local police.

Others, however, admired Bean’s organizing and soon reached out with new requests to advocate for more wrongly-convicted defendants across the South. Friends of Justice was born, and Bean began to launch more narrative-based campaigns in Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi. In every case, he said, “we realized that getting ahold of ‘story’ was most important.” So, when Bean encountered an innocent family in Church Point, Louisiana, accused of running a crack cocaine business from their home, he went digging again.

With help from attorneys and journalists, Bean discovered that inmates had falsely reported the family in order to gain generous sentence reductions. The record revealed that the informants, who were convicted drug dealers serving long sentences without parole “couldn’t even pronounce the family’s name and were writing letters to each other coordinating their stories,” Bean explained. The case unraveled when one inmate eventually admitted to reporting false testimony against the family.

Story was also critical for a group of black teenagers in Jena, Louisiana, who were charged with attempted murder but who had simply been defending themselves amid ongoing racial tensions at school.

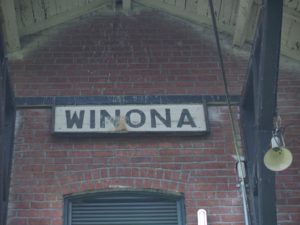

Friends of Justice is now focused on the case of Curtis Flowers, an African-American man who has been six times and convicted four times (with two trials ending in hung juries) for the shooting deaths of four people in Winona, Mississippi.

In each case, the often-prejudicial narrative swirling around small town communities proves as formidable as the prosecution itself, Bean explained. In Church Point, the real story began when the family’s young boys were spotted with white girlfriends and tension developed with local police.

In Jena, the real story began when the convicted teens mistakenly ate lunch on the “white side” of the quadrangle. Entire communities are responsible for condemning or empowering a defendant claiming innocence, he said, which is why the church must start facing society’s most pressing issues head-on. “People need to get more comfortable with areas that are existentially uncomfortable,” Bean added.

“Even in our progressive churches, there is a real limit to how much people want to know about the plight of disadvantaged people,” he explained.

“Criminal justice reform is one of those culture war issues…and that culture war cuts rights down the middle of our sanctuaries. So, people feel a strong social pressure to avoid controversial issues because they don’t want to lose their tribes. But criminal justice reform is a prophetic issue and a practical application of Jesus’ teachings about justice for the ‘least.’ So, we’ve got some work to do,” Bean said.

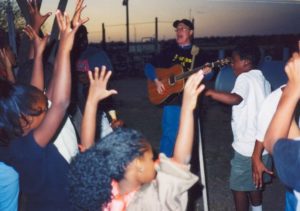

Alan Bean leads a crowd in song in Tulia, Texas, where his work began in advocating for those falsely convicted for various drug charges.

Friends of Justice is now focused on the case of Curtis Flowers, an African-American man who has been tried six times and convicted four times (with two trials ending in hung juries) for the shooting deaths of four people in Winona, Mississippi. All four convictions have been overturned. On June 21, 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 7-2 in favor of Flowers, and the case now reverts to the original trial court.

Bean is hopeful his sentence will finally be vacated after his having served more than 20 years in prison. Along the way, he said, Friends of Justice wants to help communities across the country begin to address the alarming realities that people of color face in the United States, especially in the criminal justice system. “If we really want to get radical about Christian discipleship,” Bean said, “we must talk openly about issues that primarily impact poor people of color. And we’ve got some work to do. We always have work to do.”

The award-winning podcast In the Dark, recently honored with a Peabody award, focused on Flowers’ case in its second season. Listen to learn more about the case of Curtis Flowers.

Watch this video to learn more about the ministry of Alan Bean and Friends of Justice.

The Cooperative Baptist Fellowship is a Christian Network that helps people put their faith to practice through ministry efforts, global missions and a broad community of support. The Fellowship’s mission is to serve Christians and churches as they discover and fulfill their God-given mission. Learn more at www.cbf.net.