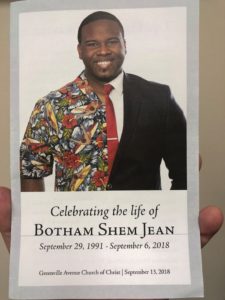

On the night of Sept. 6, in an upscale Dallas apartment building, a young accountant named Botham Shem Jean, who was black, poured himself a bowl of cereal and settled in to watch a football game. At around 10 p.m. Amber Guyger, a white police officer, burst into his apartment and shot Jean to death. She then called 911.

These facts have not been disputed. Almost everything else has been.

These facts have not been disputed. Almost everything else has been.

Amid international attention, Dallas has become embroiled in its own “O.J. moment,” a time when blacks and whites see justice in such starkly opposing ways that conversation seems pointless. City leaders have long worried that with the right provocation Dallas could become another Ferguson, the Missouri town where violence broke out after Michael Brown, an unarmed, 18-year-old African-American man, was killed by police. Community leaders fear the Amber Guyger case will be that provocation.

“If the grand jury doesn’t come back with (a charge of) murder, we may have riots,” says Jeff Warren, senior pastor of mostly white Park Cities Baptist.

The African-American community is “boiling in outrage,” adds George Mason, senior pastor of mostly white Wilshire Baptist Church.

“Dallas’ black Christians have taught a growing number of the city’s white Christians what they experience, what it is to be daily riven by ancient suffering and at the same time mended minute by minute by a God who can create precisely what despair demands: peace and justice.”

But within these dire warnings, delivered by these particular white men, is a pinprick of light. Dallas’ black Christians have taught a growing number of the city’s white Christians what they experience, what it is to be daily riven by ancient suffering and at the same time mended minute by minute by a God who can create precisely what despair demands: peace and justice.

Tributaries of anger

The deep anger in Dallas’ African-American community is fed by the past and the present. The city is last in “overall inclusion” of minorities, according to a recent Urban Institute Study of 274 cities with populations of more than 100,000.

There is both insult…

A monument to Civil War heroes still stands near city hall. It bears a giant “C.S.A.” monogram and is guarded by life-sized statues of the President of the Confederate States, Jefferson Davis and his generals, Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and Albert Sidney Johnston. The Dallas school district voted only last year to re-name four schools named after Civil War soldiers: Lee, Jackson, Johnston and John H. Reagan, an American Congressman and postmaster general of the Confederacy. Some of the city’s most prominent streets – Gaston, Ervay and Lemmon – are among those named for Confederates.

…and injury.

Photo of Dallas skyline by Andreas Dress on Unsplash

Dallas is two cities, says Warren. To the north it’s white and affluent. The church he leads, Park Cities Baptist, draws most its members from that sector. To the south, Dallas is black and economically challenged. Diners who sit at Dallas’ landmark revolving restaurant atop the Hyatt Regency tower can see those two cities defined starkly. “It’s like North and South Korea,” said one African-American woman. “As the place you’re sitting revolves to the north, you see all those lights spread out across the land. Then it revolves to the other side (with) no lights. Nothing. Just dark.”

Nevertheless, African-American influence is growing. Dallas has a large number of African-American judges. Its district attorney and police chief are African-American women.

Just a week before Botham Jean was shot to death, a white police officer who fired a rifle into a car of teenagers, killing a 15-year-old African-American boy, was convicted of murder by a Dallas county jury and sentenced to 15 years. He’d claimed that he was protecting a fellow officer who was in danger of being run down. But the second officer testified he had been in no danger. It had been 40 years since a Dallas cop had been convicted of killing a citizen. For most black activists, it was such a major win that one leader said she hardly knew what to do next.

Then Amber Guyger stepped into an apartment that wasn’t hers.

Confusion, controversy and division

News media accounts of the killing are generally in agreement about the basic elements of the story. On the night of Sept. 6, after working a 15-hour shift, Guyger said she mistakenly parked on the fourth floor of her Southside Dallas apartment building instead of the third floor where her apartment was located. The 30-year-old officer gathered an armload of items from her car and went to what she believed was her apartment. Jean had a red welcome mat outside his door, but Guyger has reported that the items in her arms blocked her from being able to see the mat, which would have signaled that she was at the wrong door. The door was not latched.

“As Dallas pastor Frederick Haynes puts it, white communities are policed and protected, while other communities, especially minority communities, are policed and preyed upon.”

Entering a dark room, Guyger reported that she saw the silhouette of a man. Believing him to be a burglar, she said, she dropped the items she was carrying and shouted commands to Jean, which he did not obey. She shot him twice. She then realized she was not in her own apartment and called 911, sobbing.

To some, perhaps especially white people in Dallas and elsewhere, the incident seemed an unfortunate accident, a tragedy all round. That may be because white people generally see law enforcement as peace officers, who risk their lives to protect citizens and ought to be given the benefit of the doubt.

But the Guyger story looked radically different to a large number of African-Americans. To them, this latest killing-by-cop showed that black men weren’t safe from police violence even in their own homes. To them, Guyger’s actions weren’t exceptional, they were merely the latest in a long list of unwarranted killings by police – licensed, armed vigilantes who regularly foment racism and violence against people of color.

As Dallas pastor Frederick Haynes puts it, white communities are policed and protected, while other communities, especially minority communities, are policed and preyed upon.

There seemed plenty to doubt about Guyger’s account. Many Dallas citizens – white and black – were shaking their heads, saying, “Something seems fishy.” Stories circulated about people in apartments nearby hearing a woman banging on the door, demanding to be let in. How could Guyger have failed to see the bright red mat that marked Jean’s door as not hers, some asked. Other residents claimed that the apartment door couldn’t have been left open accidentally because the doors close and latch automatically. Jean’s mother said her son didn’t like the dark and never would have been sitting in a dark room.

There seemed plenty to doubt about Guyger’s account. Many Dallas citizens – white and black – were shaking their heads, saying, “Something seems fishy.” Stories circulated about people in apartments nearby hearing a woman banging on the door, demanding to be let in. How could Guyger have failed to see the bright red mat that marked Jean’s door as not hers, some asked. Other residents claimed that the apartment door couldn’t have been left open accidentally because the doors close and latch automatically. Jean’s mother said her son didn’t like the dark and never would have been sitting in a dark room.

Haynes, pastor of Friendship-West Baptist, a mostly African-American megachurch, minced no words during a protest 10 days after the fatal shooting. He referred to Guyger as “that lying officer.” Guyger had been charged with manslaughter. Haynes wanted her charged with murder. The city’s police chief had put Guyger on leave. The protestors wanted the officer fired immediately.

Perhaps most egregiously, on the very day of Jean’s funeral where the 26-year-old was lauded as an extraordinary employee, a dedicated church member and a person with a smile for everybody, police released a list of the dead man’s apartment’s contents. Media accounts noted that among them was a cache of marijuana.

Haynes demanded an apology from the media for mentioning the marijuana, which he would only refer to as the “item.” Including that detail without anyone knowing whether the bag even belonged to Jean was seen by many as character assassination of a dead man, the kind of treatment African-Americans have so often been subject to. “Even though we’re the victim, it seems like we gotta prove that we deserve to be the victim,” said Bryan Carter, pastor of Concord Church.

Pastor Frederick Haynes

Haynes and other leaders called on the police department to investigate the policies and procedures that led to such killings. Had they searched Guyger’s apartment? She was the perpetrator. Instead, they searched the victim’s dwelling?

Four days after Jean was killed, two dozen black pastors held a press conference outside police headquarters. For many, Guyger was already receiving the kind of special treatment that keeps police officers from being accountable for their actions in the way other citizens might be. She had been given 72 hours before being arrested, which is standard for Dallas police officers accused of crimes. Three days had given her time to be coached, to rehearse her story and to consider evidence that might counter her story, said critics. In a similar situation, a black person would have been arrested on the spot, African-Americans contended.

Not one white Christian pastor was among the ministers at the press conference, which was hardly surprising. Dallas’ white Christian leaders seemed to be running true to historical form during racial conflict: staying silent, doing nothing, playing it safe.

This case was murkier than some other cases of police mistreatment of African-Americans in past years. This was not a white police officer slamming a slightly built teen girl onto the ground and straddling her, as had happened in a nearby suburb. This was not a cop harassing a man trying to get into his own truck and then shooting him as he ran away begging not to be shot, as had happened in Fort Worth.

Those were easy calls compared to this one. It was this one, however, that would demand that some of the city’s most influential white pastors take a public stand with their African-American brothers and sisters. Some may have wished this particular cup would pass from them. But a sizeable group of white and black pastors had become friends. And friends stick together, especially when there’s trouble. Don’t they?

Interracial friendships among pastors

The growth in interracial friendships among Dallas pastors seems to have begun in 2011, not long after Warren became senior pastor at Park Cities Baptist. He began to think about Park Cities not just as a church, but as The Church, a citywide gathering of Christians that reached across racial lines. A friend suggested that Concord Church and Park Cities, which is affiliated with the Baptist General Convention of Texas, were much alike.

Jeff Warren

Warren, who had long been interested in racial justice issues, called Carter, Concord’s pastor, and they met for lunch. They liked each other and decided to be intentional about carving time out of their busy schedules for other lunch conversations. In 2014, when Ferguson erupted into weeks of violence, Warren and Carter asked, “What would happen if Ferguson happened in Dallas? What would we do?” They realized that black and white Christians would be helpless to mediate because they hardly knew each other.

Convinced that “gospel moves at the speed of relationship,” Warren began devoting 10 percent of his time to fostering interracial friendships. Other pastors did too. The idea was that the pastors would work with their own churches but also with the larger community, says Vincent Parker, lead pastor at Golden Gate Missionary Baptist Church. “We can be conduits for healing beyond just a particular church.”

As the years went on, four loosely organized coalitions of black and white pastors formed. They and their congregations began sharing meals and working together on projects. Women from Concord joined in a book club with women from Park Cities.

Men from various churches began sharing Saturday morning breakfasts at which they would ask each other, “What’s your race story? How did your parents talk about race?” The black Christians didn’t have much to learn about race from the whites. As St. Paul United Methodist pastor Richie Butler, who graduated from Southern Methodist University and did his graduate work at Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, puts it, “I know how to flow in a white man’s world. I can do him better than he can.”

We all have racism in us, says Butler. “You have to treat racism like you do a chronic illness. You take medication so it does not overtake you. That’s a pragmatic approach.” The African-American Christians were patient and truthful explaining what their lives were like, says George Mason, Wilshire’s senior pastor. And white attitudes began to shift.

At Park Cities, Warren began talking to his congregation about why blacks and whites reacted differently to news stories. He linked the difference to systemic racism tracing it “all the way back to the first slaves to Jim Crow laws to the Civil Rights era.” When the movie “Selma” came out, Warren took his staff to see it.

“Our people were blown away,” he says.

Friendships tested by violence

On July 7, 2016, the pastors’ friendships had their first real test of unity. That summer, as police departments began to employ dashboard cameras and bystanders shot videos, scenes of police violence against African-Americans seemed everywhere.

Two days earlier, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, an African-American man, Alton Sterling, had been shot to death while pinned to the ground by police. One day later, in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, a black motorist, Philando Castile, was shot and killed by a police officer during a routine traffic stop. On July 7, approximately 800 people participated in a Black Lives Matter demonstration in Dallas to protest police violence. The 100 officers patrolling the event weren’t wearing tactical gear or carrying heavy weapons. Their interaction with the crowd was purposely low-key and friendly.

Suddenly, shots rang out. As a sniper began firing, the panicked crowd scattered, unsure where the shots were coming from. As citizens fled, police moved toward the gunfire. One of the most publicized scenes of the massacre came as a white policeman shielded an African-American woman and her son from the gunfire by putting his body over theirs.

Five law enforcement officers were killed; seven other officers and two civilians were wounded in the attack. The gunman, who was black, was a military veteran who had served in Afghanistan. As the horror unfolded on live television, the city was transfixed and afraid. Officers locked down the downtown area, confining residents to their apartments as police searched for explosives.

The next day, Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings, who is white, called Warren to ask that pastors hold a service for peace and healing. Warren called white pastors. Carter called African-American pastors.

“’We refuse to hate each other. We refuse to point fingers at one another…We refuse to not love our brothers and sisters.’”

Meanwhile, a few hundred people gathered at Thanksgiving Square downtown as Carter faced the cameras. “We refuse to hate each other,” he said. “We refuse to point fingers at one another…We refuse to not love our brothers and sisters.” Standing beside him was Warren.

The following night 2,000 people, among them 100 pastors, gathered at Concord Church for another prayer meeting. Warren was there to confess how he had benefitted from white privilege and to call on other whites to use their privilege as a lever for racial justice. Another white pastor, Todd Wagner of megachurch Watermark Community Church, confessed that he hadn’t understood why Black Lives Matter mattered until a young African-American explained it to him.

The next Sunday, pastor Joseph Clifford of First Presbyterian would tell his congregation that the meeting was one of the most powerful experiences in his life. “I was convicted of my own sin,” he said. “There is so much that keeps us from loving one another.”

The city remained tense that week and into the next as funerals began to be held. Signs proclaiming “Back the Blue” sprung up all over town. Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick called the protestors who ran from the bullets “hypocrites.” White supremacists were blowing up the Internet with hateful rhetoric and threats of violence. At the same time, some blacks criticized the African-American police chief for sending a robot armed with explosives to kill the sniper instead of negotiating his surrender more aggressively.

But many Dallas citizens, African-American and white, joined the law enforcement community and city leaders in mourning, contributing flowers and messages to an enormous display honoring the fallen at police headquarters. At Potter’s House, a 30,000-member, mostly African-American church led by T.D. Jakes, huge photos of the murdered officers graced the dais during a service in which they were lauded.

Moving the needle

For their part, the pastors who attended the prayer service at Concord came away empowered, convinced that their prayer gathering was a big factor in keeping the peace.

More pastors in white churches began to share what their new, interracial friendships had taught them. They told their congregants about “the talk” that black parents have with their sons about how they must be extremely cautious and slow to move when interacting with police. They noted that most white parents have no need for such a talk with their sons.

They worked harder at weaving together Christian faith and racial justice. “My whiteness must be dominated by my ‘Jesusness,’” emphasizes Warren. “My ‘Jesusness’ must define me more than my race.” Golden Gate’s Parker puts it another way: “A oneness in Christ must first be recognized.”

ColorOfChange delivered 170,000 petition signatures to Dallas District Attorney Faith Johnson’s office demanding that Amber Guyger be charged with murder for killing Botham Shem Jean.

By the fall of 2018, 28 pastors had swapped pulpits on given Sundays. When Friendship- West sponsored a bus trip to Montgomery, Alabama, to visit the new Civil Rights Memorial Center and the memorial to the victims of racial terror lynchings, they invited members of their sister church, Wilshire Baptist, to go with them.

Butler organized “Together We Ball,” groups of white and black pastors, police and community leaders who play basketball together. “The church can be a divisive force,” he says. “But sports is a bridge builder. Having people on a court playing ball breaks down barriers. Guys high fiving and hugging. And that leads to sharing meals.”

Some of those meals take place in another program Butler started called “Together We Dine.” The dining tables offer a setting for “courageous conversations around race.” Explains Butler, “People from different walks of life engage in tough conversations, but it’s in a safe space. We’re usually listening more than trying to change opinions. The idea is take your shoes off and put mine on.”

Butler has also started “Unity Groups,” interracial groups of laity that might meet four or five times a year. Getting church members fired up about interracial friendships, he says, encourages their pastors to step into leadership roles in the community, much like politicians getting excited about what voters want.

Last spring Wagner, pastor of predominantly white Watermark, told his congregation that race was an unbiblical idea and didn’t actually exist. He reminded them that in the 1920s Dallas had the largest chapter of the Ku Klux Klan in America. He talked about redlining, the systematic denial of various services to residents of particular neighborhoods or communities based on race or ethnicity. He quoted Martin Luther King Jr., saying injustice could only be rooted out by “strong, persistent and determined action.” And he said, “I want you to love somebody of a different people group.”

Watermark is a conservative church that opposes abortion vehemently and last year ousted a gay man who would not renounce homosexuality as a sin. Although such conservative theology may correspond with that of many African-American churches, evangelical churches such as Watermark are not known for being on the front lines of racial justice.

Says Golden Gate’s Parker: “The more conservative churches on the white side have privatized the gospel. They believe the gospel is about me and my relationship with God. It doesn’t reach to social issues. It doesn’t reach to economic issues. It doesn’t reach to racial issues. If, as an individual, I’m not a racist or don’t consider myself a racist, then it’s OK.”

At Watermark, Wagner was challenging that theological restriction head on. So were Matt Chandler at The Village Church and Gary Brandenburg at Fellowship Dallas. At Fellowship Dallas, which is affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention, members were instructed to confess the sin of racism and to “fight to kill racism as if our lives depended on it. Fight to kill it like we do all sin.”

At Wilshire, a leading congregation among moderate churches affiliated with the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, Mason was speaking regularly of racial justice. He urged members to take a stand often enough that some parishioners complained he ought to stop the politicking and stick to the Bible. Although he joked about the complaints during sermons and sympathized with some who were uncomfortable, he didn’t stop.

Warren also has been challenged by church members. “Some people in my church say, ‘Jeff, can’t you ease up?’ They’ll say, ‘Hey, just stick to the gospel,’ as if there’s an implication-free gospel.” Some of the difficulty is “white fragility,” he says, explaining that some are thinking, “’I’ve been the dominant race. I have been in a place of privilege. I don’t want to lose that. I can’t lose that.’”

His answer: “The gospel causes us to look at this differently. It does cause us to want to see justice, to want to see equality. If all the love I need is in Jesus, I have enough love.”

Park Cities has lost some members because of Warren’s stance on racial consciousness and justice. “Not many but some,” he says. How much impact have his words really had? “I haven’t seen anybody on Facebook say, ‘Hey, I’ve completely changed my mind.’”

But new, interracial friendships have proven their value by teaching people the way forward. “What we’ve learned is that empathy is the pathway to peace,” he says.

Speaking with a united voice

The pastors had spent years getting ready, consciously or not, for the day when a crisis would arrive, and with it the need to speak with one voice. Now, that day had come.

After the black pastors’ news conference, Wagner sent a text message to Carter: “Praying for you. Is there anything you wish I knew that you aren’t sure I know? Is there anything I’m thinking that you aren’t sure I am thinking? Is there anything you wish I was doing that you aren’t sure I am doing? How can I serve you? How can we serve our city together? I am trusting you will call me any time. I’m ready to listen, respond and serve.”

Other pastors were also talking with their friends. A meeting was scheduled.

George Mason addresses the fatal shooting of Botham Jean from the pulpit of Wilshire Baptist Church .

About a dozen pastors ended up in a room together. “That was when things started to get real,” says Wilshire’s Mason. He later recounted to his congregation that Jakes from Potter’s House told the white pastors: “I believe you care because you are in this room; but we need to know more than where your heart is. We need to hear you say clearly in the pulpit and in the streets that white supremacy and racism is wrong. And no more generalizations. It has to be specific. I know it will cost you something to do so, but isn’t that what Jesus calls us to do, to take up our cross and follow him?”

The pastors decided they would formulate a statement and send it to The Dallas Morning News.

Then came Sunday morning. In a show of clergy unity unlike anything ever seen in the city of Dallas, black and white ministers in some of the city’s largest, most prestigious and wealthiest churches rose at their pulpits to speak with a united voice. They demanded justice for Botham Jean and dared to say that Jesus would do the same.

At Concord, Carter told members to grieve for their city as Nehemiah grieved for Jerusalem. “The enemy can attack a city,” he said. “Maybe it’s time for God’s church to get on their knees for their city.” He ended the service with 10 minutes of prayer as the congregation swayed and cried out for the city, the Botham Jean family and for Amber Guyger.

“We need to hear you say clearly in the pulpit and in the streets that white supremacy and racism is wrong. And no more generalizations. It has to be specific.”

At First United Methodist Church, pastor Andrew Stoker’s topic was white privilege. White privilege is unearned and undeserved, and “white privilege gets all the privileges,” he said. Referring to Jean’s death, he added, “White privilege is the power to remain silent in the face of racial inequality and in the face of racial injustice.” Jesus, he made clear, would not approve.

At Watermark, Wagner used the church’s website to post his thoughts. “Speaking out against any form of injustice is not brave – it is our duty as followers of Christ,” he wrote. “It is not radical to boldly acknowledge that we have a long history of injustice toward people of color in our country. It is ignorant to deny it or say otherwise.”

That Sunday at Wilshire, Mason declared that “the preferential treatment of the officer by the criminal justice system reminds us that justice is still not blind to color – whether white, black or blue; the smear campaign of the dead man’s character immediately after his funeral is a long and nasty practice used against people of color to gain sympathy for the defendant. Lord, have mercy.”

George Mason

The last words of his sermon were blunt: “If we want to call ourselves by the name of Jesus, we have to stop defending things he would condemn and start loving people like he did. It may cost us friends. It may even cost us our life. But after three days, give or take, there will always be a rising with Christ. Amen.”

When Wilshire posted an excerpt of Mason’s sermon on YouTube, more than 2 million people clicked on the link. Among the thousands who commented, many were African-Americans grateful to hear a white pastor speak up for them and for racial justice.

On Monday the pastors’ letter was published. It was signed by 19 clergypersons, white and black, representing more than 100,000 Christians. The letter stated that Officer Guyger’s uniform should not give her special privileges. “We demand full transparency, consistency, and integrity in the days ahead as the judicial process progresses.”

The pastors had spoken in unity. Old customs, actions and attitudes were challenged. A police officer should be treated like anyone else.

Reality of unequal justice

Several weeks after Jean was killed, a “Call to Action town hall” was held at St. Paul’s United Methodist Church. After an hour or so, the meeting of about 200 people disintegrated into chaos when fist-shaking activists drowned out questions with chants of, “What Do We Want? Justice! When do we want it? Now!” When he gave the closing prayer, Butler, St. Paul’s young pastor, stood at the edge of the platform extending outstretched arms as if blessing the crowd. His voice could barely be heard over the ruckus.

A group of Anglo pastors sat together by the door, starkly conspicuous in the mostly black crowd. They had come to offer unspoken support. Earlier in the service, however, Mason had been asked if he would speak. No other white person had been among the speakers. Without prepared remarks, Mason took the floor.

“Unequal justice is real,” he declared. “Racism is real and a demon that must be exorcised from our hearts. … We want what you want, which is equal justice for all.”