In South Africa, free analog-broadcast community television stations whose programming caters to low-income majority Black townships are broke. To keep the lights on, they take advertising money from startup Pentecostal pastors who promise bewildering “miracles” and changes of fortune for jobless audiences.

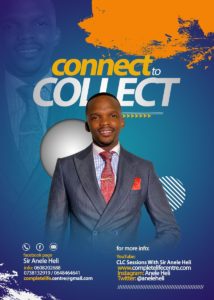

Anele Heli is a 20-something charismatic prophet-pastor in Cape Town, South Africa’s most racially and financially gentrified city. He goes by the moniker “Sir Anele,” and his weekly TV sermons on Cape Town TV, the largest nonprofit community channel in the city, attract thousands of viewers and thousands more offline. Worshippers are desperate for him to touch their heads and to ease their pain in a country with the world’s highest joblessness rate. “I’m here to change lives on TV,” Heli said. “My sermons heal diabetes, restore lost jobs, reverse divorces.”

He competes with a bevy of other prophet-pastors for slots on Cape Town TV.

Cape Town TV, set up in 2008, broadcasts about social justice issues that cater to the impoverished majority-Black/Colored townships in the city. It’s part of a string of seven other community TV channels dotted across urban townships in South Africa.

“South Africa’s community TV stations, geared for Black townships, are so poor that some go on air without licenses,” explains Kudakwashe Magezi, a poet and tech critic in Johannesburg. “Any time, they can lose their allocated signals spectrum to wealthy mobile Internet corporations. Very few up-class commercial brands want to run advertisements on bankrupt township TV stations, except these start-up pastors like ‘Sir Anele.’”

Uncomfortable dependence

In South Africa, community stations have formed a peculiar alliance with local charismatic Christian televangelists, such as “Sir Anele.” They need the preachers’ revenue to keep broadcasting and to bring vital health, education and policing news to millions of residents of the country’s decaying townships — viewers who can’t afford high-quality pay-per-view cable TV or broadband Internet TV channels.

Perpetrators of verified scams and scandals, the quacky prophet-pastor TV evangelists promise “miracles” to South Africa’s viewers. They apparently see desperate, jobless township residents as a fertile field from which they can glean money. (This is not to suggest “Sir Anele,” the TV prophet-pastor, is a fraudster).

“It’s simple,” says Mxolisi Nale, a TV consultant who lobbies for more state funding for South Africa’s community TV channels. “Each prophet-pastor pays a fee of about R40 000 ($2,500) a month to township television stations such as Soweto TV for the right to broadcast their church services in weekly three-hour slots.”

Soweto TV is a free community television station broadcasting in Soweto, the biggest township in South Africa, home to 1.27 million residents who are majority Black and low income.

The pastor, the TV, the cellular phone company

In South Africa, a “three-way highway” connects prophet-pastor televangelists, broke township TV stations and the country’s cellphone corporations — all targeting struggling majority-Black township residents, explained Magezi, the poet and tech critic.

“The transactions happen this way: Prophet-pastors pay for slots on bankrupt township community TV stations. The community TV stations get vital cash to keep the lights on, paying amateur reporters, water (and) rent, and keep broadcasting.”

Prophet-pastors recoup their money by performing sermons and “miracles” on TV and aggressively soliciting electronic cash donations and “pledges” from township residents, adding members to swell their churches. They engage in a rivalry race to net the highest viewership for their sermons — and cash “donations” for their budgets.

“There is an electronic horizontal bar endlessly appearing under the visuals of every TV sermon listing bank accounts and soliciting audiences to donate or deposit money to whoever pastor-prophet is leading a TV sermon,” reported Themba Tshuma, the program director of Mpumalanga TV, one of South Africa’s leading community TV stations. “As a community TV channel, we are not responsible for viewers’ decision to offer money to a TV-prophet-pastor.”

At the end of each month, cellular-phone corporations and prophet-pastors share cash that accrues from broke township worshipers, who are sending cellular-phone requests for “prayers and miracles” to charismatic televangelists, Tshuma said.

At the end of each month, cellular-phone corporations and prophet-pastors share cash that accrues from broke township worshipers, who are sending cellular-phone requests for “prayers and miracles” to charismatic televangelists.

“Cellular phone corporations earn from … texts sent by township TV audiences; prophet-pastors accrue donations to their bank accounts. It’s a transparent business arrangement. We, TV stations are just middlemen,” Tshuma added.

Nowhere else to go

South Africa’s pay-per-view TV channels, increasingly delivered to homes via broadband Wi-Fi, are expensive and largely cater to the affluent middle-class, which is overwhelmingly white and suburban. For reasons of editorial taste, these up-class TV channels don’t accept advertising and pay-for-slot programming from prophet-pastor televangelists like “Sir Anele.”

“Their viewers are too up-class to watch township prophet-pastor TV sermons,” explained Nale, the community TV consultant.

This leaves poor, broke township community TV channels like Soweto TV, Mpumalanga TV and Cape Town TV as the only destinations for prophet-pastors looking to woo crowds on television, round up cash donations and “pledges” into bank accounts, and compete for audiences.

Audiences at mercy of dubious prophet-pastors

Deprived township residents, dependent on dysfunctional community TV channels, are prone to be fleeced of their savings by questionable prophet-pastors performing “miracles” on screen. Nearly a dozen dubious South African township TV prophet-pastors are on trial for rape, murder, extortion, immigration fraud and “fake miracles” stunts.

A notable community TV prophet-pastor is Bishop Alph Lukau, who earned global notoriety in 2019 when he supposedly “resurrected a dead man” from a coffin live on TV and the “grateful, hungry resurrected man” quickly munched a plate of rice. South Africa’s human rights protection agency vowed to investigate the pastor-prophet’s stunt. Another township TV prophet pastor is Bishop Stephen Zondo, who is in prison awaiting the conclusion of rape, murder and extortion charges. And Prophet Shepherd Bushiri, South Africa’s most popular community TV prophet-pastor, is wanted on an international arrest warrant for charges of $7 million fraud, sex crimes, immigration fraud and fleeing a court trial.

All three TV prophet-pastors deny charges leveled against them.

“It’s the classic dilemma,” Magezi said. Poor, majority Black township residents in South Africa can’t afford high-quality pay-per-view TV or home Internet broadband. Broke community TV stations are their only source of information. Therefore, fraudster prophet-pastors lie in wait for desperate township TV viewers beset by joblessness, lack of health insurance or mental health ailments.

“The wolves in sheep-skin, the money-seeking prophet-pastors, pay for slots on the shunned community TV stations,” he said. “The TV stations get cash to scrape by. Prophet-pastors recoup their money by performing TV ‘miracles’ and aggressively requesting cash donations to a bank account. Cellular phone corporations get a cut of the cash revenue from desperate viewers … text messages.”

Ray Mwareya is a freelance immigration journalist who lives in Canada.

Related Articles

Anticipating a new day in immigration policy, a pastor, pilot and bricklayer keep an eye on Biden’s next move / News, Ray Mwareya and Nyasha Bhobo

Facing increased attacks, Canada’s Muslim women take up self-defense classes / News, Ray Mwareya

Baptist layman offers lessons from South Africa on overcoming civil war / News, Jeff Brumley

45 years after the Soweto uprising, religious leaders call for more racial harmony among South Africans / News, Anthony Akaeze