In the heart of the Bloomfield neighborhood in Macon, Ga., our Baptist church and school served as the place where 300 white people came every Sunday for church and throughout the week for school.

On Sunday, we had a bus ministry that provided a church service for Black kids on the other side of the parking lot in the gymnasium. They were not to cross the parking lot to attend the service in the main auditorium. And on the one Sunday they did, there were complaints from some of the older white members of the church.

Rick Pidcock

Throughout the week, we attended classes while hearing the sounds of guns and canons firing across the street at the Civil War reenactments. The Civil War, we were taught, was not about slavery, but about “state’s rights” against the same “big government” that Bill Clinton and the Democrats were promoting at the time. We were taught that God decreed at the Tower of Babel that the races were to remain distinct, and that Black people descended from the curse of Ham.

Our conservative evangelical white culture was completely segregated from the culture of our Black neighbors.

But then on Tuesdays and Thursdays, a group of 15 white teenagers would file into the choir room to sing our favorite song, the old spiritual “Little Innocent Lamb.”

We didn’t know anything about the song or about spirituals in general. In fact, we probably could count on one hand the number of Black people we knew, despite the fact that our campus was surrounded by predominantly Black neighborhoods. But the song had a great rhythm and a fun sound. And so it became our little white choir’s greatest hit.

Is cultural appropriation ever acceptable?

Over the past 10 years, as technology and social media have converged in our worlds, a discussion within the academic and religious worlds of choirs has been growing regarding whether it is appropriate for white choirs to sing songs that were written in Black communities or in the context of the Black American experience.

Rollo Dilworth

The choral conductor Rollo Dilworth observes, “As a choral composer of music that reflects the African American experience, I had been getting lots of questions in the last decade about cultural appropriation. The fear really comes from not wanting to offend, feeling like the outsider, feeling that maybe I don’t have a right, as an outsider, to participate in a musical tradition that does not reflect my own.”

During a breakout session about cultural appropriation in choral music at the 2019 Chorus America Conference, Dilworth said that “subject appropriation” happens in the arts when artists use people or components of other cultures as the subject of their own art. And “content appropriation” happens when choirs sing songs or utilize styles from other cultures, while “object appropriation” happens when choirs utilize an instrument from cultures other than their own.

But is this always inappropriate? Are we never allowed to sing songs or play instruments that were created in other cultures?

Richard Rogers, communications professor at Northern Arizona University, is quoted in a 2019 journal article suggesting that cultural appropriation can be acceptable through a cultural exchange, in which cultures participate in a “reciprocal exchange of symbols, artifacts, rituals, genres, and/or technologies between cultures with roughly equal levels of power.”

In the same piece, writer Brianna Fragoso says cultural appropriation can be acceptable through cultural appreciation “when elements of a culture are used while honoring the source they came from.”

“Are we never allowed to sing songs or play instruments that were created in other cultures?”

Dilworth himself suggests that cultural appropriation can be acceptable through cultural consumption “in which we harmlessly (and sometimes unknowingly) interact with a culture that is not our own.”

On the other hand, Dilworth identifies unacceptable cultural appropriation as “theft” when someone takes something from another culture without permission, as “assault” when the appropriation harms people from the other culture, and as a “profound offense” when the appropriation goes against the other culture’s sense of right and wrong.

Recognizing power dynamics

There are power dynamics at play in such musical performances, however, because of the history of where the music came from and what prompted it.

Cultures — including musical cultures — developed within Black and enslaved communities existing within cultures of white supremacy and oppression. These abusive power dynamics are reflected in the songs of the slaves and of the Black church.

In The Spirituals and the Blues, James Cone speaks to this power dynamic, saying: “Art and thought cannot be separated; and thus there is something contradictory about the idea of ‘discovering the rich vein of music that existed in these half-barbarous people.’”

“These abusive power dynamics are reflected in the songs of the slaves and of the Black church.”

No matter how creative the slave songs were, they still were considered to be qualitatively lower in culture due to where they came from within the social hierarchy. In fact, Cone explores accusations within German musicology that the slave songs were “mere imitations of European compositions.”

Surely, the white establishment thought, those lower on the hierarchy were not capable of producing art that was as respectable as their art. And yet today, predominantly white choirs, including university choirs and church choirs, celebrate the music borne out of oppression as a respected art form worthy of performance — even if they fail to acknowledge the abuses that produced it.

A genre deserving respect

In an interview with Baptist News Global, legendary conductor Anton Armstrong of St. Olaf College said, “This music has to be treated with the same integrity and respect as the music from the Western European-centric canon, whether it’s Bach or Brahms or whoever.”

Anton Armstrong

He added, “It’s a testimony to the Africans who were put into slavery that they could sing of hope, they could sing of deliverance when the immediate world around them showed nothing but cruelty and degradation.”

Unfortunately, when many white choirs choose to sing the spirituals, they fail to approach the songs with the respect they deserve. Armstrong noted: “Too many people may hear a recording or they hear a live performance and think, ‘That would be neat to do with my choirs.’ And they don’t do any more research beyond that. And that’s where the issue of a negative cultural appropriation happens. For somebody just to do a spiritual because it’s rhythmic and it’s fun for the singers and never discuss the meaning of the text, never discuss how in the context of the life of that enslaved human being did these songs come about, reduces them and doesn’t pay them dignity.”

For a white choir to sing spirituals in a way that is respectful requires hard work and detailed study, Armstrong said. “I’m a person who encourages the use of dialect, but proper. I don’t do a German Bach motet with bad German. I learn how to speak the language.”

Anton Armstrong conducts the Massed Choirs and St. Olaf Orchestra during the 2019 Christmas Festival broadcast on national TV.

Thus, for white choirs to utilize the songs that were born in Black communities, they need to respect those communities enough to dismantle the hierarchy of cultural power dynamics and learn the techniques and stories of the people from which those songs were born.

An intelligent, resourceful song of suffering and hope

For those who are interested in learning more about the history and performance practices of singing the spirituals, Armstrong recommends Way Over in Beulah Lan’: Understanding and Performing the Negro Spiritual by Andre Thomas, whom Armstrong has known 44 years. Thomas is the first African American president of the American Choral Directors Association. And Armstrong considers him a Titan in the industry.

Thomas explores the historical development of the spirituals from the oral tradition to printed collections to the arrangers who have shaped the art over the past 150 years. He also provides performance advice for taking the music from the page to the stage while covering such practical issues as diction, rhythm and tempo. And then he provides a bibliography for many additional resources to explore.

Armstrong also recommends The Books of the American Negro Spirituals by James Weldon Johnson as a collection of songs that include a preface and history for each song.

Another resource Armstrong suggests learning from is In Their Own Words: Slave Life and the Power of Spirituals by Eileen Guenther. In addition to providing a scriptural, historical and performance overview of the spirituals, she also explores how specific contexts such as the slave master’s house and the slave quarters shaped the songs of the most vulnerable slaves. She explores their rituals, rebellions and escape attempts.

“They could send messages to each other that white people never figured out until it was too late.”

One of the most fascinating aspects of the spirituals is how they were written to communicate messages to one another that only they would understand. Regarding these “telegraph” or “escape” spirituals, Armstrong said: “They could send messages to each other that white people never figured out until it was too late.”

He illustrates:

“Wade in the water. Wade in the water, children. Wade in the water. God’s a gonna trouble the water.’ You’re going to go cross that river to get out of here.

“Follow the drinkin’ gourd. For the old man is a waitin’ for to carry … Old man was maybe sometimes Harriet Tubman herself or somebody else who was going to get you to freedom. The big dipper was the drinkin’ gourd.

“They gave instructions. Keep your lamps trimmed and burning. The time is drawing nigh. Don’t go to sleep tonight, people. We’re going to break out of here.

“They were intelligent. They were resourceful people.”

When history touches the present

For Armstrong, diving deep into the history of the spirituals can help everyone become more aware of the injustices marginalized communities face today. “We may not be held in physical chains like an African was 150 years ago. But we are in economic chains. We certainly are in a racial pandemic. We are dealing with some of the same atrocities of life that those Africans put into slavery faced.”

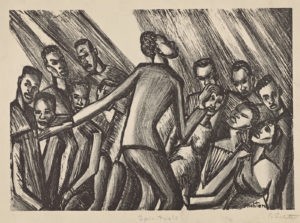

Lillian Richter’s “Spirituals” (circa 1935-43). Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Art and Artifacts Division, The New York Public Library.

Being willing to face our past — to the point of seeing, loving, grieving and hoping with our brothers and sisters until our eyes are opened to the injustices the oppressed still feel today — is vital for reversing the hierarchy of cultural power dynamics and respecting our neighbors.

Armstrong asks: “Can you have respect for this genre of music and the people from which it emanates, and not just a historical respect, but a respect for people today? If we start to have respect, then we might start to acknowledge our sins of omission and commission. Then we might have the chance to build trust, something that is sorely lacking in our social environment today.”

The audacity of hope

Armstrong believes that when given the respect and dignity they deserve, the spirituals can heal our communal wounds and bring us together. “While I totally concede that this music, these sorrow songs, these slave songs came out of a race of people,” he said, “they really depict human emotions, human conditions. Because of the sense of trial and tribulation but yet joyful celebration over adversity, these songs are relatable to people all over the world because they speak of a human condition.”

“I may not be able to solve cancer …, but I can give people through music a healing balm.”

The way spirituals speak to the human condition has the capacity to bring hope and transform lives.

“That’s why I want a young person — white, Black, brown — to know these songs,” Armstrong said. “So that when they get depressed, they feel alone, or they are bullied, then there is something they have to restore them, to uphold them, to lift them up and get them to the next day.

“I’m sick and tired of hearing young people taking their lives because they don’t fit into a binary idea of male/female. I’m sick and tired of seeing young people in so much pain. When you sing songs like this, and if you can really be vulnerable, you let those words and those haunting melodies into your heart and your mind, they will make a difference.

“I may not be able to solve cancer. I may not be able to solve Alzheimers, but I can give people through music a healing balm,” he concluded. “And that’s what these songs are. They offer hope. They offer a belief that something will be better.”

Rick Pidcock currently serves as a Clemons Fellow with BNG. He recently completed a master of arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five kids and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder.