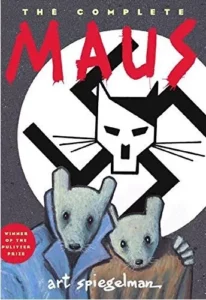

Do some parents really think banning books will keep their children from swearing or thinking about sex? My guess is that surreptitious middle school book clubs already have formed all over the country to read Maus. Nothing like telling prepubescent children not to read something to send them straight to Google.

Perhaps parents are not terribly realistic about what their children already know. In 2017, I went to the women’s march in Portland with my godchildren. The boy had just turned 13. Another marcher in front of us carried a sign that read “Planned Parenthood. Don’t (obscenity) with us. Don’t (obscenity) without us.”

Susan Shaw

I heard the boy laugh. “Do you know what that means?” I asked. “Oh, Susu,” he replied, “I’ve known what that means for years.”

Of course, banning books is nothing new. The first book was banned in the United States in 1637. An English businessman decided he did not want to abide by the strict rules of the Puritans, so he left them to establish his own colony at what is now Quincy, Mass. He wrote New English Canaan, which attacked the Puritans so harshly even the New English were appalled, and they banned the book.

Today, many people, it seems, still think some ideas and words and stories are beyond the pale — even if those stories are historical truths about slavery. As an educator, I’m especially taken aback by their assumption that children and teens — and sometimes even college students — need to be protected from ideas. Rather than teaching kids how to think, many Christian adults would rather teach them what to think. “Teach,” however, is the wrong word. “Indoctrinate” is more accurate.

These adults are not wrong, however, about the dangers many books pose to uncritical acceptance of dogma, whether that dogma is religious faith or white supremacy or some combination thereof. Books certainly threaten bias, certitude and teeny, tiny worldviews, and I see why some folks might get worked up over that.

The sad truth, however, is that children who miss out on the wonder of books about people and worlds and ideas beyond the scope of their family and church are also missing out on the difficulty and the joy of learning to think for oneself.

“Books certainly threaten bias, certitude and teeny, tiny worldviews, and I see why some folks might get worked up over that.”

In a difficult childhood as a fundamentalist Southern Baptist girl, I found my refuge in books. I didn’t even know then that many of the books that were expanding my horizons and challenging my narrow frameworks had been banned or challenged at one time or another — The Grapes of Wrath; As I Lay Dying; Of Mice and Men; Animal Farm; The Lord of the Rings; Absalom, Absalom; To the Lighthouse; All the King’s Men; A Good Man is Hard to Find and Other Stories; A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

I was fortunate enough as a high schooler to have really good English teachers who taught me how to read a text, how to grapple with ideas different from my own, and how to let the text speak to me. Books pushed me and affirmed me and showed me a world so much bigger than Rome, Ga., and Southern Baptist fundamentalism.

Yet it was these same Southern Baptist fundamentalists who also told me I could think for myself because God could speak directly to me, and I could go directly to God without need for a mediator. They also told me I could read the Bible for myself and that the highest authority was the individual conscience before God. I took those lessons seriously, and so when books opened up new ways of thinking to me, I followed them. After all, if what I believed really was true, then what did I have to fear from other ideas? Certainly, truth could withstand a challenge.

Yet it was these same Southern Baptist fundamentalists who also told me I could think for myself because God could speak directly to me, and I could go directly to God without need for a mediator. They also told me I could read the Bible for myself and that the highest authority was the individual conscience before God. I took those lessons seriously, and so when books opened up new ways of thinking to me, I followed them. After all, if what I believed really was true, then what did I have to fear from other ideas? Certainly, truth could withstand a challenge.

A number of years ago, when The Last Temptation of Christ was made into a movie, the uproar was great. I wasn’t really that interested in the film until then, and so, like middle schoolers searching out banned books, I took myself to the nearest theater to see what all the hullabaloo was about. Frankly, I was disappointed. I already had heard every idea in the film in seminary, and so I didn’t find the movie all that groundbreaking or controversial.

My mother was appalled when I told her I had gone to see it. “Well,” I said, “It’s your fault. You taught me not to just accept what other people tell me, but to make up my own mind.” “Well,” she responded, “I did raise you girls to think for yourselves.”

To her credit, when my high school English teacher sent me home to ask her if I could read The Grapes of Wrath, my mother said, “Yes,” without hesitating. Even after I read the book, I wasn’t sure why Mr. Moss made me ask. He was teaching me to read for images and themes, metaphors and ambiguities, and I saw in the book a beautiful picture of Communion. I thought the ending was perfect, even as a naive, clueless fundamentalist Southern Baptist 15-year-old who was learning how to read books.

Banning books is not about preserving the faith; in fact, it’s the opposite of faith. It suggests a faith so weak it cannot survive the challenge of other ideas. It suggests soul competency only counts when everyone agrees. It suggests stubbornness, closed-mindedness, ignorance and fear are truer signs of faith than intellectual engagement, dialogue across differences and willingness to live in ambiguity.

“If I doubted the competence of the individual soul before God (including children’s souls), I’d be worried about books too.”

So, I guess, if I doubted the competence of the individual soul before God (including children’s souls), I’d be worried about books too. It’s so much easier to keep believing all the things we already believe if we don’t have to deal with those nasty ideas that might make us uncomfortable or cause us to question.

Instead, we should look at books (as well as movies, music, articles and even social media) as opportunities to seek out and engage with ideas that are new to us, that challenge us, that even make us want to throw said books across the room. And we should want kids to have these opportunities to learn and grow as well. This is one way we teach them to love God with their minds — by letting them use those minds.

Susan M. Shaw is professor of women, gender and sexuality studies at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Ore. She also is an ordained Baptist minister and holds master’s and doctoral degrees from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Her most recent book is Intersectional Theology: An Introductory Guide, co-authored with Grace Ji-Sun Kim.

Related articles:

That time I went to the school board meeting to speak against banning books | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

From Texas to Tennessee, evangelical parents are trying to take the ‘public’ out of public education | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Is it now illegal to mention the Tulsa Race Massacre in the classrooms of Oklahoma? | Opinion by Alan Bean